The Writing Life

Biography explores Connell’s ‘quaint mania’

As a writer and as a man, Evan Connell could be hard to read.

Enigmatic, introverted, emotionally distant and averse to the publicity chores like interviews and personal appearances that publishers typically require of writers, Connell, c’47, was fiercely independent, iconoclastic and uncompromising not only in his personal life, but also in the subjects he chose to explore in 20 books

published in a half-century career.

Mrs. Bridge (which established his reputation when it appeared to widespread acclaim in 1959) and Mr. Bridge (which followed in 1969) are quintessential Kansas City novels whose emotionally remote title characters were instantly recognizable to most Americans, even as the books’ inventive structure—short, impressionistic sections that eschewed traditional plotting and narrative drive—prodded mainstream readers to reconsider what a novel could be. Yet his most well-known work, surprisingly, was a nonlinear, boldly innovative indictment of the Indian Wars as exemplified by Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s resounding defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Son of the Morning Star.

Elsewhere, in collections of short stories, novels, essays and in nearly uncategorizable forays into history, philosophy, religion, art and alchemy (Were they fiction? Poetry? Nonfiction? Even publishers and critics struggled to put a label on his work), he constantly defied expectations and challenged readers, setting out on wildly esoteric journeys to deeply explore the things that interested him, with seemingly no concern for whether or not anyone would follow along. He simply wrote what he wanted, publishing conventions be damned.

“He is undoubtedly among the best of recent American writers, one who possessed an extraordinary range of talent and output,” former Kansas City Star journalist Steve Paul writes early on in Literary Alchemist, the first full-length biography of the Kansas City-born Connell, who died in 2013. “Yet, reflecting the characteristic cruelty of the predominant cultural measuring apparatuses, he is also one of the least known.”

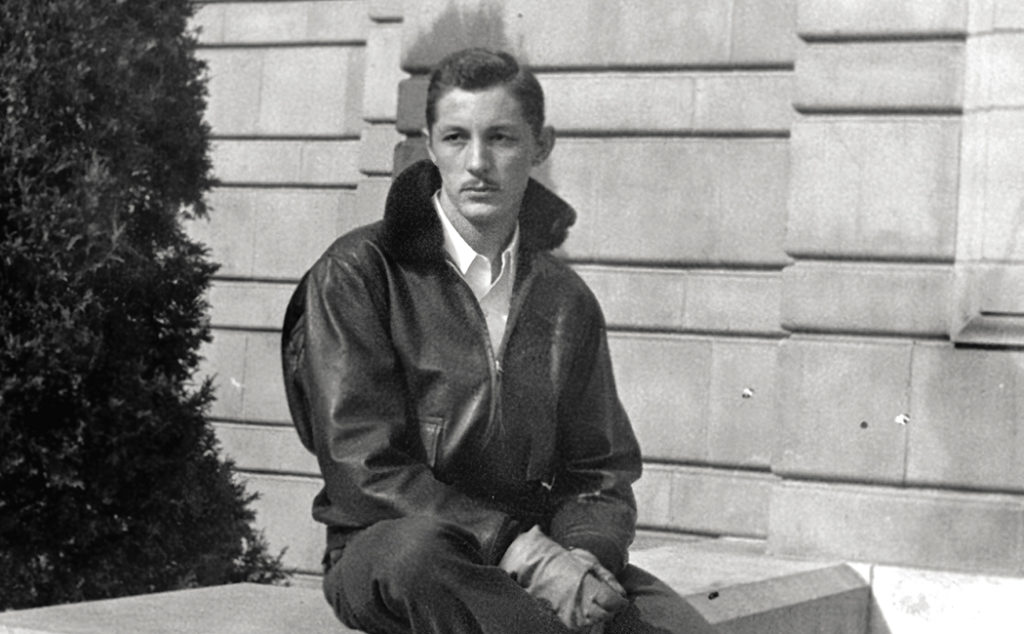

Undaunted by Connell’s “relatively sparse paper trail,” the author of Hemingway at Eighteen: The Pivotal Year That Launched an American Legend sets out to portray the “writer’s writer” who even friends concede was essentially unknowable. He finds Connell’s youth and adolescence “hard to trace,” aside from the hints he later left behind in his writing. The college years—first at Dartmouth and then at KU, where he finished his degree in three semesters and a summer term after serving as a Navy pilot during World War II—are more enlightening. On the Hill he pledged Phi Kappa Psi and helped found the Bitter Bird, a campus humor magazine to which he contributed drawings and writing; studied with the painter Albert Bloch, who later became the subject of one of his first published short stories; and cut a dashing figure in his leather flight jacket. He made training flights from the naval air station in Olathe, Paul reports, until one spring day when a fellow flyer, a war buddy also enrolled at KU, buzzed Memorial Stadium, causing both men to lose their flight privileges. He also studied creative writing with the novelist and editor Ray B. West, who became a longtime mentor and champion.

Literary Alchemist shines welcome light on events and milestones in the life of a writer who shunned public attention; especially enlightening are descriptions of Connell’s world travels and his deeply held connection to nature, which illumine his most adventurous, genre-busting books. Even more valuable, though, is the literary appraisal put forth by Paul, whose 40-year tenure at the Star included a stint as editor of the paper’s book

section. Synthesizing a wide range of sources, including book reviews, award citations and personal notes sent to Connell by contemporaries such as John Updike and William Styron, and adding his own incisive analysis of Connell’s formidable work, Paul reminds us that even books that did not generate the broad adoring readership granted his most successful titles still added to his exalted reputation in the literary world. With each new project Evan Connell pushed the boundaries of literature, unshakable in his conviction that what mattered beyond all else was this “quaint mania,” as he called the obsessive writing about topics that captured his imagination and challenged his redoubtable intellect. In that regard, Literary Alchemist would seem to do all its subject could ask: It sends us back to his books with renewed appreciation for his lifework, challenging bold readers to claim this “writer’s writer” for our own.