What's Going On

In June Kevin Willmott’s latest collaboration with Spike Lee, “Da 5 Bloods,” began streaming on Netflix. A story of four Black veterans of the Vietnam War who return 50 years later to claim the remains of their fallen squad leader, Stormin’ Norman, and the shipment of gold he died retrieving, the film is the third that Willmott, KU professor of film and media studies, has written with Lee.

“Da 5 Bloods” was scheduled to premiere at Cannes in May, where Lee was also set to make history as the first “person of the African diaspora” to serve as jury president at the celebrated international festival. But COVID-19 erupted, prompting festival organizers to cancel. The world got its first look at the film, in which the Black Lives Matter movement is contextualized as the latest example of a long history of African American patriotism that dates back to Crispus Attucks, two weeks after the death of George Floyd, amid the most widespread social justice demonstrations the country has seen since the Vietnam era.

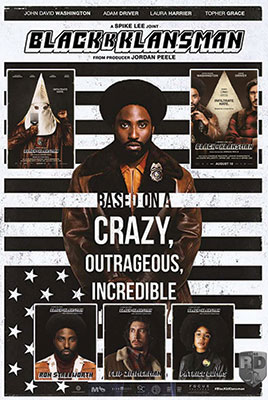

In its examination of the Black soldier’s Vietnam experience, the film toggles between 1971—when the bloods shared an intense camaraderie forged in combat and honed by Stormin’ Norman’s fierce lectures on Black power—and contemporary Vietnam, a land unvanquished by the United States military but utterly seduced by its fast food chains. Though it focuses on roughly the same historical era as “BlacKkKlansman,” which won Lee and Willmott the 2018 Academy Award for best adapted screenplay, “Da 5 Bloods” strikes a darker tone. Where “BlacKkKlansman” found satiric humor in the absurdity of a Black policeman’s infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan and eerie presaging of current events in Grand Wizard David Duke’s grandiose political ambitions, “Da 5 Bloods” in its wider frame deals with more tangled issues, such as war’s long reach into soldiers’ psyches and time’s relentless erosion of the bonds of brotherhood and youthful idealism. Where “BlacKkKlansman” tipped its cap (with a sly wink) to Blaxploitation films such as “Superfly” and “Shaft,” “Da 5 Bloods” mines a grimmer, more haunting cinematic vein that runs from the corrosive gold fever of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” to the heart-of-darkness moral corruption of “Apocalypse Now.”

Both films focus on historical problems that, 50 years on, still confound us. And both, in a sense, were overtaken by current events. In Willmott and Lee’s script for “BlacKkKlansman,” the final scene was to be a Klan cross-burning in the 1970s. But before filming started, said Lee in a 2019 interview, “Charlottesville happened.” The August 2017 Unite the Right rally in Virginia led to street brawls between white nationalists carrying Nazi and Confederate battle flags and counter-demonstrators. A young woman, Heather Heyer, was killed when a man plowed his car into a crowd. “I knew that was the end of the movie,” Lee said. The Charlottesville Coda, as the film’s final sequence became known, includes footage of the vehicle attack and of Duke, who attended the rally.

“The joke was that David Duke literally wrote himself into the film,” Willmott says of the surreal moment when then got trumped by now. “He was there at Charlottesville. We could not really avoid it. It was literally a commentary on our film. And so in that sense it was clearly a choice on our part, but it was also just kind of fact, really.”

For “Da 5 Bloods,” the sense of fact overtaking film arrived when the movie was already finished. After Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, the movie’s Black Lives Matter scene carried a different urgency, because the chants coming from the screen echoed those in the streets.

But to chalk that up to a simple twist of fate, coincidence rather than design, would be a mistake.

During an online Q&A June 26 organized by the Free State Festival, the Lawrence Arts Center event that showcases film, music, art and ideas in downtown Lawrence each summer, a viewer asked Willmott: How does it feel having current events turn out to be your best promoter?

He chuckled before answering. “Well, I think the key to that is all my films tend to really speak to what’s happening at the time,” he said. “I think the reason for that is if you talk about what’s really happening, your movie will always be speaking to what’s going on in the world.”

“Movies really made me love history. I learned so much as a kid at the movies.”

Growing up in Junction City, Willmott, 62, was at the theatre nearly every weekend. “Grown-folks movies, not Disney,” he’s quick to add. “If you went to Disney movies in my neighborhood, they’d kick your ass.”

Double features—westerns and monster movies especially—were big. The first film that made an impression: “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.”

“That movie really messed me up in terms of just the power of it, especially the music, and the style. I think I was in third or fourth grade. And I could just tell it was different from other films.”

Willmott was learning he was different too. When he asked for the movie soundtrack for his birthday, his mother took him to Gambles, an appliance store that sold records. “I pointed to that album, and she said, ‘This is what you want?’ Yeah, that’s what I want. She could not understand what this was about, you know?” he says, laughing. Later his brother told him, “We always thought you were weird, but that’s when we knew.”

By sixth grade he was writing movie scripts that featured his friends as characters and reading them aloud in class. (“I didn’t know what a screenplay was, so they weren’t structured right,” he says. “All I knew was I wanted to make movies.”) World War II films and “problem pictures”—social-issue movies of the sort that propelled Sidney Poitier to stardom in the 1960s—sent him to the history books.

“When I would hear about Iwo Jima and Tarawa and Wounded Knee or anything that was real, I would go look that stuff up. I’d want to know what was really going on. So what movies did for me was really kind of raise my curiosity about history.”

Blaxploitation films and James Bond movies were big, too. Action mattered.

“Because the thing you would always do was, you’d go to the movie, then you’d come home and you’d go in the backyard and play that movie,” he recalls. “I consider that kind of where I learned to write dialog and use my imagination. That whole thing that kids do where you’re playing a story in your head—that’s great training for a writer and great training for a filmmaker. Because that’s ultimately what I still do today.”

An early thrill was seeing “Superfly” on the Fort Riley military base in a theatre packed with Black soldiers, many of them returning from Vietnam.

“Not an empty seat in the house,” Willmott recalls. “The energy in that room was just insane. You gotta remember with movies like ‘Superfly’ and ‘Shaft,’ when those movies were coming out Blacks had never seen anything like this before, had not seen images like that of themselves. And these soldiers were from all over the country, a lot of them from big cities. They could relate to the film in a way I couldn’t, and they were older than me, too, obviously. It was a really adult film, and the language and all of that was just so refreshing because it directly spoke to them, and it was really great to see the appreciation they had for the film.”

Around the neighborhood he heard the stories and learned the elaborate dap handshakes of these “bloods,” as the Black soldiers called themselves. The term reflected the bond of men who counted on one another like family in a war zone where Blacks made up 31% of combat troops and 23% of the casualties, despite representing only 11% of the U.S. population. In Vietnam they frequently faced the same prejudice and discrimination as back home and often were stuck with the most hazardous or unpleasant duty, a situation one soldier described as “first-class dying” and “second-class treatment.” From their stories, and from the lingering effects of the war that he saw in the fathers of schoolmates and in his own family members (including a cousin who came home from Vietnam but was never the same), he learned how trauma planted overseas could take root in his world—and blossom most terribly when a Vietnam vet suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder murdered a friend of Willmott’s mother.

He dramatized that murder in his first movie, “Ninth Street,” set in a Junction City neighborhood that once was home to a thriving jazz scene but by 1968 was a declining area of juke joints and strip clubs catering to GIs from Fort Riley. He drew on his Junction City memories again when Spike Lee showed him a spec script, “The Last Tour,” by Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo. Originally optioned by Oliver Stone but never made, it was a tale of four white soldiers who journey back to Vietnam to recover a lost comrade and a stash of gold bars. Willmott and Lee saw a chance to dramatize something they believed was missing from cinema’s reckoning of the era: the Black Vietnam experience.

They recast the characters as Black men (named after the five original members of the Temptations, Paul, Otis, Eddie, Melvin and David) and wrote into the script songs from “What’s Going On,” Marvin Gaye’s classic 1971 concept album inspired by letters between Gaye and his brother, a Vietnam veteran.

“We flipped it,” Lee has said of the rewrite. “Put our flavor on it, some barbecue sauce, some funk, some Marvin Gaye. And there you have it.”

At the start of a new project, Willmott and Lee sit down in the Brooklyn office of Lee’s production company, Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks, and talk big picture. They comb through any existing script line by line and decide what to keep, what to replace. Both are attracted to stories from history that have the potential to be relevant today, and once they decide on the themes and plot elements they want to pursue, Willmott comes back to Kansas and starts writing the first draft.

“We have a kind of unspoken understanding with each other,” Willmott says of why the partnership works. “We’re about the same age, and I think we both had very similar kinds of experiences growing up. We’re both professors, and I think that love of film and that belief in the power of film links us. I think Spike appreciates my voice and I appreciate his ability as a director. We don’t talk about it at all, really. We don’t have to explain much to each other. Once we figure out our take on the film, he turns me loose and I give it to him and then he gives it back to me and we just keep sharing drafts back and forth like that through email. But I think he trusts me and he’s given me a lot of respect in that way, and I have nothing but the utmost respect for him.”

In “The Last Tour,” the cowriters saw a solid adventure story with echoes of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” about old comrades searching for riches, and the greed and distrust that gold fever sows.

“We kept all that,” Willmott says, “but what we did was use the opportunity to really turn it into a movie that focused on the Black Vietnam experience. The Black Vietnam experience is a treasure trove of things; it’s such a big world and such a unique kind of experience that it really kind of takes over the film in a sense, because most of that has not been explored much in other movies. There’s usually a Black character in other Vietnam movies, but there was not a movie that really focused on our experience.”

In 1984 journalist Wallace Terry published Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans. Terry went to Vietnam in spring 1967 to report a Time cover story on Black soldiers in the war and returned that fall as a Time correspondent, later becoming chief of the magazine’s Saigon bureau and the only African American correspondent on permanent assignment in the country. Before departing in 1969, Terry took a two-month leave of absence to travel the country and interview Black soldiers. Bloods was part of his larger project to document a part of America’s Vietnam experience that he believed was overlooked as the culture began grappling—in histories, memoirs, novels and movies—with the war’s legacy.

In his introduction, Terry noted that Vietnam marked the first time that Black soldiers were fully integrated in combat—and in leadership roles. “At that moment the Armed Forces seemed to represent the most integrated institution in American society,” he wrote. “Uncle Sam was an equal opportunity employer.” Yet the Black soldier’s contributions were often downplayed or distorted onscreen. Discussing Oliver Stone’s “Platoon,” which came out two years after his own book and won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director, Terry said, “Nowhere do you see Blacks in any kind of heroic or leadership situation.” While praising the film for capturing “the horror, terror and trauma of the war like no other,” he lamented that it failed to rise above Hollywood stereotypes in its portrayal of Black soldiers. According to Terry, veterans he talked to felt the same. “They’re furious,” he said. “Everywhere they say, ‘We still haven’t had our story told.’”

Willmott heard some of those stories as a kid. Working on “Da 5 Bloods,” he says, “I thought a lot about the things I saw growing up in Junction City during those late ’60s, early ’70s—the good and the bad.

“The good was I saw that brotherhood and I saw that love that soldiers had for one another, the dap handshakes and the pride in being Black and all of those things that were new things at that time. That had a huge influence on me as a kid. But also the bad things, the destructive things.”

The climax shows the brotherhood and love they had for each other,” Willmott says of “Da 5 Bloods,” which features strong performances from veteran actors, including the late Chadwick Boseman, center. “For me, one of the main points of the film is we all need to find that.”

The easy camaraderie of war buddies shines in the film’s opening scene, as the four vets happily greet one another in the glittering lobby of a Ho Chi Minh City hotel. They are survivors, bonded by their experience and by their respect for Norman, who was not only their squad leader but also “our Malcolm and our Martin.” In flashbacks to the war, Norman is seen as a heroic leader in the field and back at base, where he educates the other four about new ideas of Black power and Black pride. (In a June piece for The Ringer, Eric Drucker wrote that in the film’s war flashbacks, “Chadwick Boseman’s depiction of Stormin’ Norman provides all the heroism and leadership from a Black soldier in a Vietnam movie that Terry craved.”) After they discover that a chest they’ve been sent to recover contains gold, they agree it should be used as reparations to support the struggle for equality and freedom in their communities—rights that they and other Black soldiers are supposedly fighting and dying for in southeast Asia but are denied back home.

That all-for-one determination to do the right thing—so steady in 1971—feels much more tenuous on the return trip 50 years later, especially as their adventure spirals into a fight for survival. The question of whether that conviction, and their friendships, will survive is what drives “Da 5 Bloods” from buddy picture/heist caper to something bigger—something actor Jonathan Majors, who plays Paul’s son, David, who accompanies the men on the journey, calls “a film for now.”

Willmott is especially proud of the brotherhood among the men.

“I think that’s a really important element of the film. I’ve seen a lot of comments where people talk about how they have not seen that before, not seen Black men love each other like that, support each other like that. I think that’s something we don’t see in movies near enough.”

Kansas City film and theatre critic Lonita Cook, moderator of the Lawrence Arts Center’s Q&A, came of age with Black films such as “Krush Groove,” “Harlem Nights” and “Boyz n the Hood,” but she says Willmott’s take on affection among Black men and boys is different than those movies.

“What I think is unique about his body of work is the context in which that affection is depicted,” Cook says. “It is a rarity in American films to find Black men outside of concrete ghettos. To set Black male characters on an excursion in Vietnam is to set loose the Black male figure from a one-note imagination.”

For Willmott, exploring territory where mainstream cinema rarely ventures mostly meant making his own films before he hooked up with Lee. In the outspoken Brooklyn-born film icon, he found a kindred spirit: They share a desire to “bring the past into the present,” Willmott says, by finding the story elements that link history to now.

“When you make movies that are about what’s going on in the world—it doesn’t matter what the movie is about, typically—but if you are trying to really go to those places that movies rarely go, they almost always connect with current events in one way or another,” Willmott says. “I think that’s the power of going there.”

Willmott has made a career of going there.

After “Ninth Street,” he wrote and directed “CSA: Confederate States of America.” An audacious satire posing as a British documentary, “CSA” sprang from a simple premise: What if the Confederacy had won the Civil War? A mix of provocative what-if history and a knowing commentary on the stubborn persistence of racism in American culture, the film proved a hard sell in mainstream Hollywood but earned Willmott his first invitation to Sundance. Its relevance has only grown, especially in the past four years, as white supremacy has moved from the fringes to the mainstream of American politics. The grim punchline of “CSA” was that the Confederacy did win, an argument bolstered by the historical record (Reconstruction, Jim Crow, segregation) and popular culture. (Many of the outrageously racist marketing ploys played for laughs in the movie are revealed at the end to have been real products.) In a July op-ed for the Kansas City Star, Willmott wrote, “We are currently living in the third act” of the 2004 film, and have, in fact, “always lived in two countries: The CSA and the USA.”

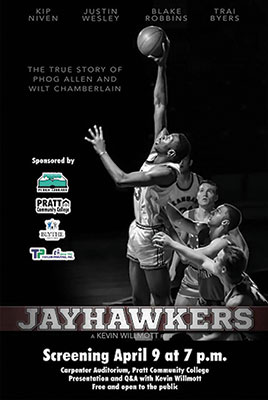

The movies that followed bridge past and present directly (as in “Destination: Planet Negro,” 2013, in which the characters try to escape 1930s Jim Crow oppression by flying a rocket ship to Mars, but end up instead—to great comic effect—in 21st-century Kansas City) and indirectly (as in “Jayhawkers,” 2014, the story of Wilt Chamberlain’s leading role in efforts to desegregate Lawrence during his playing days at KU, in which the film’s narrator, jazz saxophonist Nathan Davis, d’60, is threatened with expulsion for playing “boogie-woogie”—a true story that also reads as an early skirmish in the culture wars, foreshadowing more recent battles over hip hop and rap culture).

Willmott’s films “use history as a tool to chisel away at political apathy, racial and economic inequality,” Cook says. “The single greatest moment in a movie that folds history onto today is the scene from ‘CSA’ where the slaves are being caught and it is exactly an episode of ‘Cops.’ There are no words needed. It is this scene, for me, that drives the central mystique of the Willmott canon.”

The word choice is telling: The tool is a chisel, not a sledgehammer.

“Kevin is a master of cultural satire,” Cook says. “His movies function by employing a tone that makes the movie likeable, even as he dismantles the deceptions of your comfort zones. A Kevin Willmott film is a film that is going to do some tough things, but his audience is going to root for those things to happen. That is the space he works in.

“So, where race is concerned, Willmott films invite white viewers to gaze not only upon the Black figure, but on themselves. That is incredibly rare. Black performers are usually expected to answer the curiosity of white voyeurs through their performance while simultaneously absolving them of their societal misconduct. Kevin don’t let that go down.”

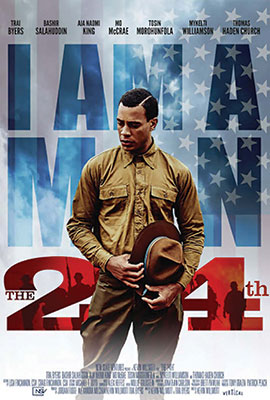

Taken as a whole, Willmott’s films bring to mind the famous William Faulkner line: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Consider his most recent project, “The 24th.” Released in August, the film is based on the story of the U.S. Army’s all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment, buffalo soldiers who fought alongside Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders at San Juan Hill and joined Black Jack Pershing’s battles against Pancho Villa. Sent to Houston in 1917 to guard Camp Logan, then under construction, the men of the 24th endured demeaning Jim Crow laws and violent beatings at the hands of the Houston police. After one particularly brutal episode in which two policemen beat a local woman suspected (wrongly) of hiding two soldiers sought by the police, 150 troops marched on the city, where they were met by armed whites; 11 civilians, five policemen and four soldiers died. After a court martial, 19 soldiers were executed and 41 received life sentences.

Willmott learned of the incident—called by some the Houston Riot, by others the Camp Logan Mutiny—when he saw a photograph that called it the largest murder trial in American history.

“I had not heard about it, had not ever heard it referenced anyplace. I had to research it. It’s this forgotten little slice of American history that is incredibly important and none of us knows about it. That kind of history is always at the top of my list, especially when it resonates to today.”

Willmott wrote the screenplay more than 20 years ago. Finding no takers, he put it aside and moved on to other projects. When Trai Byers, now a star of the hit TV show “Empire,” was his student, Willmott told him the film’s lead would be a great role for him. They rewrote the script together, starting around the time Willmott was working on “BlacKkKlansman.”

“That movie speaks directly to what is going on right now with George Floyd and the Black lives movement and the riots that we’ve been having in some of our cities,” Willmott notes. “Because as Dr. King says, a riot is the language of the unheard. That problem of being unheard, it has been a problem for over 100 years in this country. The thing that I’ve been saying about ‘The 24th’ is that one bad policeman can destroy a city. That was true over 100 years ago with Houston, and it’s still true today with Minneapolis: One bad policeman almost destroyed the city.”

Actor Tosin Morohunfola, c’10, who appears in “The 24th” and also starred in “Destination: Planet Negro,” says that when pondering Willmott’s seeming knack for telling historical stories that current events prove eerily relevant, “there is a larger dynamic worth acknowledging.”

“America is really bad at righting its wrongs. It’s not good at acknowledging past crimes, its social mistreatments.” So why then shouldn’t a story about injustice from 50 or 100 years ago still be relevant today “when there’s been no restorative justice, no precedent set for redeeming the soul of the nation?” Morohunfola asks. “How can we even be surprised that the country continues to repeat-offend its original sin?”

“The 24th” offers obvious parallels between 1917 and now, he says, but in a way that might challenge viewers who are accustomed to a more conventional cinematic formula

“Unlike many history films, where people just feel bad for the Black oppressed people, I think some viewers will be more conflicted: ‘Well, I don’t justify what they did, I can’t stand behind what they did.’ That’s a nice piece of privilege that they are able to, from a distance, pass ethical judgment on people in very different, drastically oppressive circumstances just trying to find a bit of agency and control. I think it is the responsibility of the viewer to focus on the context, not just the aftermath, of their actions: what the country has done to force people into a place where they feel the need to riot. That is the straight line it draws from the past to the present.”

The climax shows the brotherhood and love they had for each other,” Willmott says of “Da 5 Bloods,” which features strong performances from veteran actors, including the late Chadwick Boseman, center. “For me, one of the main points of the film is we all need to find that.”

Near the end of “Da 5 Bloods” a pivotal scene kicks off the resolution of the film’s big question: Can the bloods be bloods again, united by their solidarity as comrades and Black men? The group has splintered, and as one hacks his way through the jungle alone, the others approach a temple ruin, where they prepare to make their last stand. Over the scene plays Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On”—dedicated, in a flashback to 1971 featuring North Vietnamese radio propagandist Hanoi Hannah, “to the soul brothers of the 1st Infantry Division, Big Red One.”

The version used in the film strips away the party chatter, the funk bass and soaring horns and Gaye’s own harmonies to spotlight his plaintive lead vocal, lending a deeply haunting quality to the moment. It’s also a reminder of the complexities faced by Black soldiers in Vietnam, who were reminded constantly (not only by Radio Hanoi propaganda but also by the Confederate flags flown by fellow American soldiers) of the dissonance between their stated mission—defending democratic freedoms in southeast Asia—and the denial of those same freedoms back home. That the concerns Gaye airs in the song about endless war, generational conflict and the need for understanding instead of brutality remain urgent today adds to what is already an extraordinarily layered moment. The question the film explores—can a spirit of unity be recaptured once lost?—could well be a question for America herself.

“The thing that has probably changed the most is I’m just working all the time now,” says Willmott of his 2018 Academy Award for best adapted screenplay. “Mainly writing, but I hope to get back to some of the things I want to do. That’s the challenge for anybody in the industry: You can always work, but you rarely get to do what you want to do.”

During the arts center event, Lonita Cook asked, What can movies do to help us off this “hamster wheel” of history repeating itself again and again?

“Yeah, we’ve been on this cycle forever in this country: We just repeat the bad things over and over,” Willmott replied. One thing movies can do, he suggested, is point that out. What “Da 5 Bloods” tries to do “is connect what everybody was talking about and what was going on in 1971 to today,” he continued. “And the same things Marvin was talking about in ‘What’s Going On’ are still happening today.”

What does that say about America, I ask him later, that we seem to keep grappling with the same problems decade after decade?

“We have a great country that could be a whole lot better,” he says. “The challenge of America is we’re a divided country, and we’ve always been a divided country. That’s what ‘CSA’ was all about.”

In his Kansas City Star piece, Willmott argues that ever since 11 states seceded from the Union, the U.S. has been in a rolling civil war; the conflict didn’t end at Appomattox, but transformed into a cold war that continues to this day. The battle is between two opposing cultures: A USA that seeks to expand freedoms and a CSA that seeks to limit those freedoms in the name of white supremacy.

While he celebrates recent milestones such as NASCAR banning the Confederate flag, corporations embracing Black Lives Matter, and the retirement of advertising icons like Aunt Jemima as evidence that “the USA is having a comeback,” Willmott also allows that we can’t topple every statue. “Yes, we must grudgingly accept the failings of these past cultural norms and backward beliefs,” he writes. “Not every owner of slaves and fighter of Native Americans can be eliminated from America’s ugly past. Our complex, bloody, racist history is literally embedded into the DNA of the nation.”

Rather than try to rub out that stain, Willmott’s ever-growing body of work testifies, better to write it large on the big screen, with films that remind all who are willing to meet their challenging gaze that history is an ongoing story. The pages are turning still, and the end remains to be written.

Now Showing

“CSA: Confederate States of America” (2004) Amazon Prime, Hulu

“Destination: Planet Negro” (2013) Amazon Prime

“Jayhawkers” (2014) Amazon Prime

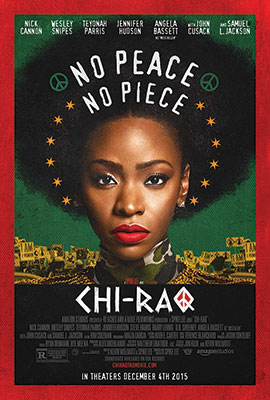

“Chi-Raq” (2015) Amazon Prime

“BlacKkKlansman” (2018) Amazon Prime

“Da 5 Bloods” (2020) Netflix

“The 24th” (2020) Amazon Prime, iTunes, Video on Demand

Coming Attractions

In June, Hyde Park Entertainment and Warner Music Group announced that Willmott will write the screenplay for an Arthur Ashe biopic. The project is now in the research stage.

“I’m looking at his life,” Willmott says. “He had a big life. He had a lot of adven- tures and did a lot of traveling and met a lot of important people, and each one of those you have to become a little bit of an expert on.”

Also in the pipeline:

“No Place Like Home,” a documentary based on C.J. Janovy’s 2018 book about LGBT activism in Kansas

“I, Too, Sing America: Langston Hughes Unfurled,” a two-part documentary about the influential African American writer, who spent part of his childhood

in Lawrence

Completed screenplay for Netflix about former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass