What lies beneath: KU students, faculty search ‘Bloody Benders’ property

An archeological investigation of the southeast Kansas site aims to unearth new clues in infamous 1870s murders.

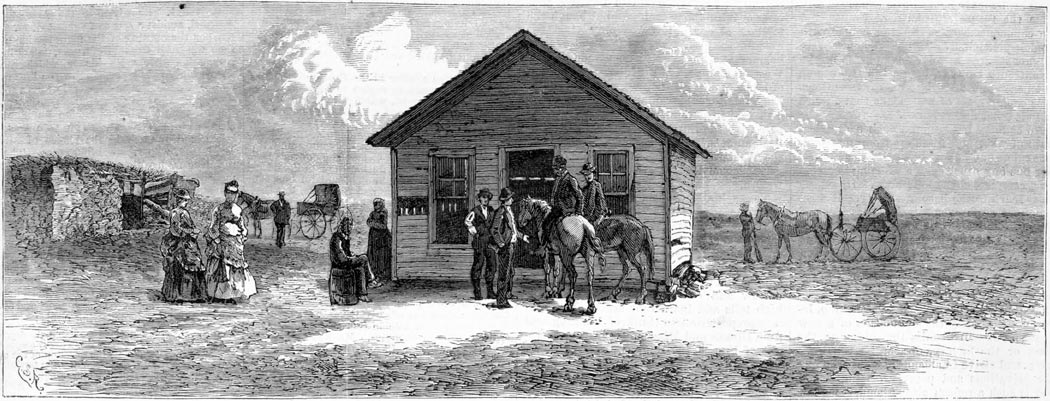

To tired, hungry travelers on the southeast Kansas prairie in the early 1870s, the Bender family cabin offered a welcome waystation. The Benders—John Sr.; his wife, Anna Marie; and their adult children, John Jr. and Kate—had arrived in Kansas in 1870 and established their homestead about 8 miles northeast of the town of Cherryvale, along the Osage Mission Trail, and regularly opened their home to those passing through the lonely expanse.

But the Benders’ hospitality belied nefarious intent: The family robbed and brutally murdered at least 11 patrons of their modest inn between 1871 and 1873.

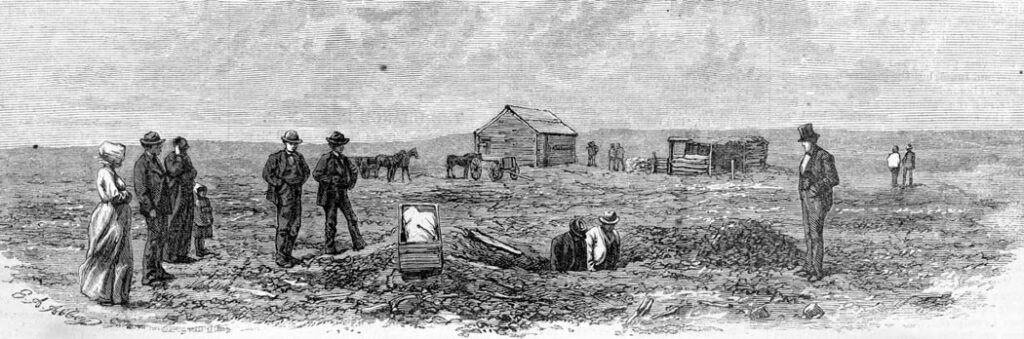

The Benders’ dark deeds came to light only when Alexander York, a Kansas state senator, set out to retrace the last known steps of his missing brother, William. York’s search led him to the abandoned Bender property, where in May 1873 investigators found the bodies of William and other missing travelers buried in the orchard.

By then, the Benders had fled the state, their unknown fate lending the story the enduring allure of mystery, and their violent crimes earning them the name “Bloody Benders.”

Now, students and faculty in KU’s anthropology department are looking to add details to the 150-year-old account through a scientific search of the land on which the events unfolded.

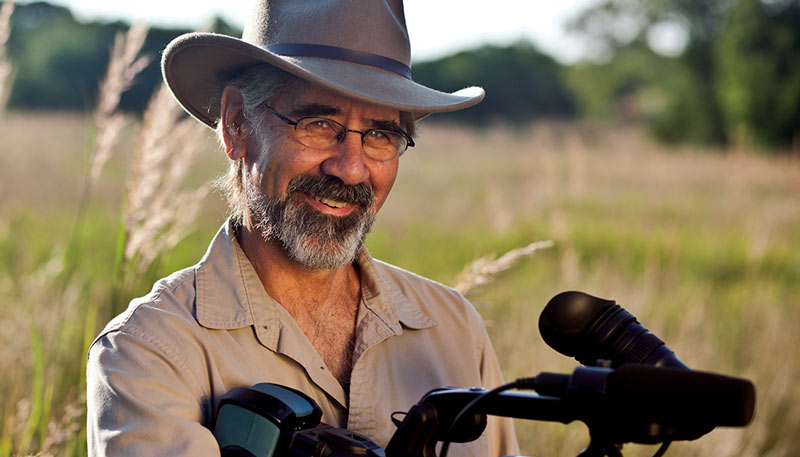

“We hope to find where everything was situated on the property—where the Bender house was, where the barn was, and maybe where some of the graves were,” says Lauren Norman, assistant professor of anthropology, who over the summer led a two-week field school for archaeology students on the Bender property, about two hours south of Lawrence in Labette County.

The project doubles as valuable, hands-on education: “The archaeology track requires a field school component, so this allows students to fulfill that without having to go too far,” Norman says, noting that the time and cost to travel to far-off archaeological sites can present barriers for some students. “We hadn’t run a local field school for a while, so I thought this might be a really great opportunity for students to work on a historic site as well as a site that generates a lot of interest.”

The 162-acre property is owned by Bob Miller of nearby Independence, who purchased the land at auction in February 2020. Long intrigued by the Bender tale, Miller wondered what additional information the land, in the right hands, might reveal.

“I wanted to bring in people who have the knowledge of what to do and how to do it, and who have the workforce and the equipment,” Miller says. He reached out to a few organizations and other universities in the state in early 2022 and says KU’s anthropology department was the best fit. “KU was interested in doing all the things I wanted to do,” Miller says. “And I knew it would benefit students to have a place to get archaeology experience that’s closer to home.”

On-site work began in summer 2023, when Blair Schneider, g’12, PhD’18, associate researcher and science outreach manager for the Kansas Geological Survey, led the first field school. She and students used remote sensing technology to identify anomalies in the soil beneath the ground, setting the stage for Norman and students to begin excavating some of those unusual areas this summer.

The two-year effort has turned up about 1,200 artifacts, Norman says, including pieces of broken tableware, broken glass from windows and containers, wagon parts, and nails and other materials likely used to build the cabin.

“The artifacts themselves are interesting, but they’re only about 20% of what we’re interested in,” Norman says. “Where they’re found, the context in which they’re found, is more important to us. That can tell us a lot. When you’re able to say, ‘This is next to that’ versus ‘This is over here,’ you get a better understanding of the people and their behaviors.”

The KU team records GPS points for each artifact, then brings the items to Lawrence to be cleaned, cataloged, photographed and analyzed, with some items then sent elsewhere for further analysis. Norman says KU will continue to work at the Bender property for two more summers, with the goal of gleaning as much as possible about not only the Bender story, but also about Kansas during the 1870s.

“A lot of places in Kansas were occupied over and over again, but because of the morbid history of this, people didn’t do anything with the land until the late 1950s, 1960s, and that’s when they started farming it,” Norman says. “But otherwise, it was just left.” Findings from the site might thus offer a unique glimpse into Kansas frontier life.

For Miller, who would ultimately like to see a museum dedicated to this sliver of Kansas history—perhaps containing a replica Bender cabin—created in a nearby town, both the progress and the process itself have been gratifying.

“The KU students have a lot of excitement and energy,” Miller says. “They’re young, they’re learning, and it’s just been a lot of fun to be around them and learn from them.”

Megan Hirt, c’08, j’08, is associate digital editor for Kansas Alumni magazine.

Illustrations courtesy of HathiTrust Digital Library

Photos courtesy of Lauren Norman

/