All in the Eyes

Should that day arrive when you find yourself horizontal in a hospital, Daniel DeJong is a physician you should want at your bedside.

The Wichita hospitalist is, by all evidence, low-key, attentive, kind. He cares about his patients, colleagues, co-workers and employer. He promotes productive interaction and positive outcomes, for the illnesses he treats and the professional relationships that envelop his working day.

He is a medical doctor and a photographer, a physician-artist who humbly says that his journey includes “no real dramatic story.”

DeJong, c’10, m’14, m’18, grew up in Overland Park, and, thanks to the blessings of a healthy childhood, his exposure to health care professionals was mostly limited to visits with his pediatrician. For some reason, though, he decided he wanted to become a doctor—“It was always something I felt like I wanted to do,” DeJong explains—so he studied biology as a KU undergrad, taking up the photography hobby while working as a residential adviser on Daisy Hill, and continued on to the School of Medicine, first in Kansas City and then Wichita, and remained in Wichita for his residency.

He and his future wife, Courtney Rooney DeJong, d’10, DPT’13, met in middle school, but did not become close until reconnecting at KU Medical Center, where Courtney, a sport science major, studied physical therapy. She joined him in Wichita during his residency, both presuming they would return to Kansas City when Daniel finally became an attending physician. They discovered instead that Wichita was the place to start their family. They liked the community, their church, their work, and saw no need to look elsewhere.

“It was kind of a long string of events,” DeJong says dryly, happily, of his undramatic arc.

Then came the drama.

Last year, as the grind of COVID-19 wore on and on and on, and each 10-plus-hour shift blurred into the next, day after day, week after week, Daniel DeJong thought to bring his camera to work.

The hobby he’d first nurtured as an undergrad had long since taken hold, and he’d spent hours studying online instructional videos while carefully exchanging and upgrading expensive camera bodies and lenses. Finally established with a family and career and an active life away from Ascension Via Christi St. Francis— the Wichita hospital where he works as a member of the Sound Physicians hospitalist group—DeJong never lacked for new and exciting opportunities to make images. A young son and daughter saw to that.

Until, that is, the pandemic locked him into the cycle now so achingly familiar to caregivers the world over. It finally occurred to DeJong that if he wanted to make some new photographs, his options were limited to boundaries imposed by the pandemic.

“I didn’t have a grand vision initially,” he says. “In fitting with the theme of my photography, it was much more of a process of finding my way there, rather than any big plans, like saying, ‘This is a project I want to do.’”

Careful not to interrupt life-saving work or ever photograph any patients, DeJong began making images of his St. Francis colleagues wearing their personal protective equipment, “just to have a portrait, something to remember, to kind of document it.” He shared the photographs with his subjects, and word began to spread on social media and online chat rooms for hospital employees.

His hospitalist group asked DeJong whether he’d be willing to contribute images for a yearbook, of sorts, to document the remarkable time of COVID. For those photographs, DeJong occasionally brought in an inexpensive backdrop, but as he again began roaming hospital corridors, seeking nurses, pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, housekeepers and cafeteria workers, he trimmed the process to its raw basics.

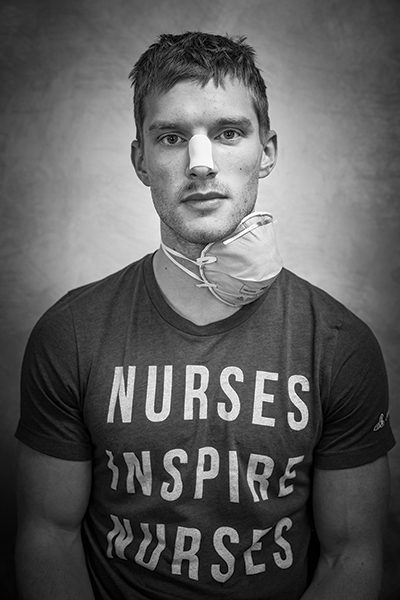

Usually working with no tripod, backdrop or supplemental light, DeJong would come in on his days off to photograph exhausted caregivers during their breaks— nurses leaning against a random wall or a doctor standing defiantly in the middle of a long hallway. Most wore their full complement of PPE, although one young nurse chose to reveal the nose bandages and bruising brought on by endless hours working in an N-95 mask.

“While you can’t recognize many of us behind our PPE,” pulmonary disease physician Maggie Kennedy Hagan, m’88, m’91, m’94, said in January, “his photos allow the community to get a glimpse of what our world has been like the past 10 months.”

DeJong is too modest to claim a grand creative vision, but his decision to shoot in black and white reveals true artistic instinct.

“It simplifies a lot of what’s going on,” he says. “We have these big blue gowns, different colors of hats and gloves, there’s all these flashing lights and machines, it’s all very chaotic, almost cartoonish. Black and white gets down to the emotional piece of it.”

His co-workers came to admire DeJong’s photography and wanted their own portraits to be memorable, so some chose not to shower or shave beforehand, preferring instead to “look how it feels, being worn down and rugged and tired.” With limited visual distraction, and most subjects wearing heavy-duty masks, DeJong’s images tell the story of COVID-19 through one particular portal.

“He was able to really bring out the spark in people’s eyes,” says Sam Antonios, m’09, Ascension Via Christi’s chief clinical officer. “This is about a whole team, and how a whole team of hospital providers came together to take care of patients. They really, really stepped up, and he was able to capture that in ways that I would have a hard time describing just using words.”

As the story of his remarkable images began to spread outside the hospital’s insular walls, from a Via Christi news release to a prominent feature in the Wichita Eagle and beyond, DeJong fretted about attention falling upon himself and his images rather than the daily achievements he chose to document and celebrate.

Yes, the creative outlet was personally beneficial “as a way to help process through grief and loss,” but the photographs themselves were always about, and for, others, honoring their relentless dedication to the grind, he says.

“OK, come in, put on all this gear, put your mask on, put your hat on, put gloves on, put your gown on. You can’t really talk to people very well, or you’re shouting through your mask. Do what you have to do, get through the day, go home, rest, and come back and do it again. And again.

“And so, for me, it was important to have a way to thank everybody, and acknowledge what everyone was doing. My hope and focus were on giving something to people who were going through this so they could remember.”

Rather than prompt particular poses, DeJong told his subjects, “Just do you want.” He required mere seconds to capture the moment in time, preferring documentary-style authenticity over stage-managed portraiture.

“It was genuine,” he says. “The people who are smiling are just smiling on their own, the people who are tired are genuinely tired, and everything in-between. There’s some cool moments that happened spontaneously, whatever people felt at that time.”

Stark, black and white images of utter exhaustion, exhilaration, fear, pride and peril invariably call to mind a certain style of combat photography that focuses on individual combatants and medics rather than sweeping views of complex battlefields. DeJong hesitates to link his images, or even his work as a physician fighting through COVID, to actual combat experienced by members of the military.

“I have seen plenty of things in the news that make that connection,” he says, “but I cannot imagine. I’ve never been in a combat scenario, so I don’t mean to belittle anything that people have gone through in those situations.”

And yet …

“When it was at its thickest, there were a lot of days when it was notably emotionally hard. Not just, ‘We have this sick person, what are we going to do for them?’, but the weight of all of it. There’s just too much death or too much suffering, and it definitely has an emotional toll on all those involved.”

As COVID’s chaos stretched into a seemingly endless test of will, DeJong’s colleagues embraced his photography as a reminder of the delicate balance of focusing on patients as people, not statistics, while also caring for their own well-being.

“These photographs certainly feel, to some extent, like a time capsule,” Antonios says. “What I think it will show, years from now, is that what really matters to people are other people, and the sense of community. What mattered was not the news, not the numbers; what surfaces, at least to me, is that people care about people and care about being nice to each other and capturing each other’s essence.

“When we look back at this, what we’ll remember the most is how people cared for each other. The humanity is what we’ll all remember.”

It is the only dramatic story that matters.