Hunger for Knowledge

“I go to events on campus just because there’s free food. I went to the housing fair, and it’s like, ‘I know where I’m living; I don’t need to be here.’”

“I don’t really have anything, so I’m going to have a fruit cup for dinner and wait until breakfast.”

As campus stirs from its summer slumber in late August and starts gearing up for another academic year, Mount Oread can seem like a rolling food fair. Hawk Week, the Universitywide welcome for new Jayhawks, unfurls in a cornucopia of free meals and snacks meant to make new arrivals feel welcomed and energized to dive into college life. As classes begin, dozens of student organizations, academic units, culture hubs and student services dangle free food as a lure to compete for students’ attention. Hawkfests and UnionFests, global brunches and veggie lunches, block parties and mingles and mixers abound, with bars and pubs beyond campus adding their own Happy Hour enticements to draw hungry students. As fall slips by, routines set in: Tuesdays are Tea at Three in the Burge Union, Thursdays are Veggie Lunch at Ecumenical Campus Ministries, and home games mean the Student Alumni Network’s Football Friday lunches at the Adams Alumni Center. Everywhere you turn, it seems, are hot dogs, burgers, barbecue, vegan tacos, cookies and—always, inevitably, inescapably—pizza, pizza, pizza.

For significant numbers of students at KU and across the nation, however, deciding what to eat is more complicated than merely sussing out which free buffet offers the tastiest treats. Research studies and surveys in the past few years have shown that students pinched by tuition hikes, rising textbook costs, stagnant wages and eroding state and federal support for higher education find it increasingly difficult to make room in their budgets for food, adding another potential obstacle to the quest for a college degree: hunger.

Conclusive data on the precise extent of the problem is elusive. A report this January from the U.S. Government Accountability Office examined 31 separate studies of hunger on campus and found that estimated rates of college students experiencing “food insecurity” varied widely, from 9% to more than 50%. But clearly the issue is real: All 14 schools selected by the GAO for closer study were found to be tackling student hunger in some way. All were providing free food through campus food pantries, most were offering emergency funds to help students buy food, and many had added centralized student services to support students’ basic needs, including helping them apply for benefits such as SNAP, the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The report also concluded that almost 2 million at-risk students were potentially eligible for—but were not receiving—SNAP benefits.

At KU, two research studies have looked at hunger on campus. In 2016-’17, senior Ike Uri, executive director of the student-led Center for Community Outreach, surveyed second-, third- and fourth-year undergraduates as part of his honors thesis and found that 54% of respondents could be considered food insecure under U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) guidelines, with 35% exhibiting very low food security, the department’s most severe category of food insecurity.

In 2018, Stacey Swearingen White, professor in the School of Public Affairs and Administration and a faculty fellow in the Office of Student Affairs, conducted a survey that also included first-year and graduate students as well as follow-up surveys and focus groups. Data collected by White and PhD student Kelsey Fortin, d’13, g’19, suggested about 32% of responding students at KU were experiencing very low food security according to the federal guidelines. Their group discussions and individual interviews with students—some of which are quoted here—provide a glimpse of the challenges students face as they try to balance the demands of completing a degree with the need to fulfill the most basic of human needs.

When Emily Doffing arrived at KU in 2017, the freshman from Wichita’s south side knew little about Mount Oread or Lawrence. The first in her family to attend college, she didn’t feel comfortable living off campus, but KU housing was too expensive for her budget. Doffing had earned a Pell Advantage grant and other scholarships, but her family lives below the poverty line and she is mostly on her own when it comes to paying for school. So she found an apartment close to campus and began looking for work.

New to town, new to college and new to living on her own, she struggled to find a job. Before long she was struggling to find enough to eat.

“Rent was high and my family was having a hard time financially and couldn’t help me out, so it was just a combination of things,” Doffing says.

She took the first job offered her, with KU Dining, “and for a while I just relied on the one meal they give you per shift.”

Doffing says she started to question whether “people like me, people who are low income” can make it in college.

“When you’re adjusting to college you’re adjusting to a whole different culture, you’re adjusting to living on your own, and food insecurity affects not only your health, it affects your mental health as well. The thoughts that, ‘I can’t do this; this is just too impossible,’ start up and a lot of times you blame yourself. It can be really hard to battle it alone.”

“When you first get to college you don’t think it is going to be as expensive as it is. When you buy books and stuff, things add up very quickly. Then you probably get through half the semester and realize how much you should have budgeted for food.”

According to the USDA, food security means access at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. The department defines food security along a range: high, marginal, low and very low. Individuals and families in the high and marginal categories are considered “food secure.” They face no or very few concerns about getting food of the quality and quantities they need.

People in low and very low categories are classified as “food insecure.” Low food security is defined as “reduced quality, variety or desirability of diet” with “little or no indication of reduced food intake.” People in this category may be getting plenty of calories but insufficient nutrients.

Very low food security (the category experienced by one in three KU students who responded to Uri’s and White’s surveys) is defined as “multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” People living with very low food security are very likely hungry, but, according to the USDA methodology, food insecurity and hunger are not the same. Food insecurity is a “household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.” This can be measured with some accuracy through survey data. Hunger, on the other hand is “an individual-level physiological condition that may result from food insecurity”—a personal, physical symptom that’s much harder to measure precisely.

For the 5.6 million American households found in a 2018 USDA survey to be dealing with very low food security for at least part of the year, the distinction is hardly comforting. More than 80% of these households reported cutting meal sizes or skipping meals entirely, being unable to afford balanced meals, and eating less than they should. Nearly 70% had not eaten despite being hungry and 47% lost weight because they did not have money for food. More than 30% reported not eating for a whole day because there was not enough money for food, and 25% said this had occurred in three or more months.

For Dana Comi, a PhD student and graduate teaching assistant in English, the strain of food insecurity on Mount Oread is often written on her students’ faces.

“I have students come in who just look horrible,” says Comi, who keeps granola bars and snacks handy to give out during office hours. “Sometimes it’s because they’re sick and they’re just pushing through the day; sometimes it’s because they pulled an all-nighter. But often they’re just hungry and haven’t eaten.”

Reasons vary, say Comi and others who frequently encounter hungry students. Busy schedules, lack of cooking skills, and youthful inexperience can play a role. But often students are simply overwhelmed by college costs.

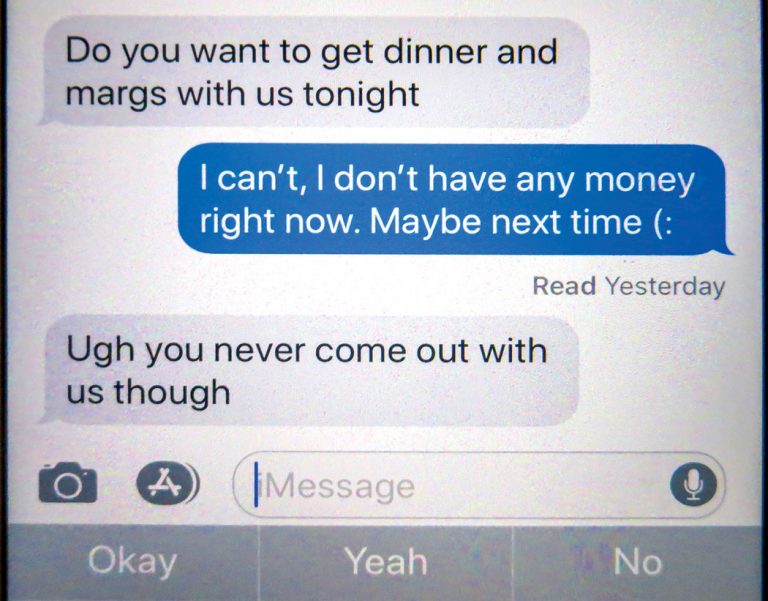

“They might be struggling to pay rent, pay for gas, pay utilities, pay for food,” Comi says. “And food is the first thing to go, because it’s the one necessity you can control. You can’t not pay your rent or your car insurance, but you can choose not to eat.”

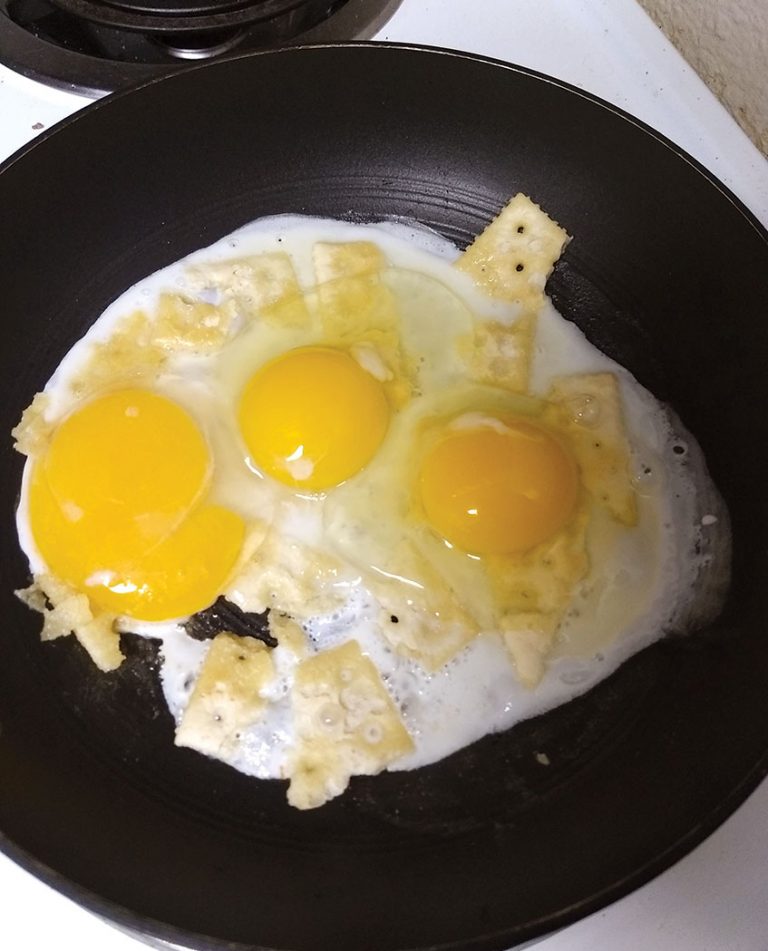

L: 48 for five bucks | M: Dinner with the Chef | R: Too late for the free food

Comi has seen students stop coming to class because they don’t get enough to eat: “They just don’t have the energy,” she says.

Carsten Holm, a TRIO SES student success specialist in the Center for Educational Opportunity Programs, has seen it too. “Every once in a while I meet students who are in tears over not being able to make ends meet and get a decent meal,” Holm says. “There’s a real sense of desperation. I know there are students who drop out because of it.”

Both Uri and White caution that there are limits to their survey data, including relatively low response rates. But both believe the problem of food insecurity at KU is real. Uri, c’17, saw it in friends and in students who showed up at the Campus Cupboard, a food pantry established by and for KU students, where he often worked during summers when volunteers were scarce. “There were people who were not coming to school with a lot of money,” he says, “and when corners needed to be cut in the budget, it was often food expenses.”

White’s understanding of the problem deepened when she asked a handful of survey participants to document their food experiences for a week. Their cellphone photos of meager meals (which became the basis for an exhibition she organized in March at the Kansas Union gallery, “Looking at Food (Insecurity),” are a bracing reminder that campus hunger is a harsh reality that can’t be fully understood by statistics alone.

“The survey measures may not be quite accurate, but the really important point to make is I know it’s a serious issue at KU,” White says. “Knowing the precise numbers is less important, in my mind, than knowing that this is a problem for large numbers of KU students.”

“I would feel bad taking food from a pantry because I assume someone needs it more … I should let other people use those resources, and I can just make do with what I have and that’s gonna be fine.”

At Ikigai Noodle, a weekly dinner hosted by Westwood House, home to KU’s Lutheran Campus Ministry (LCM), students begin arriving well ahead of the 6 p.m. start time. Campus minister Shawn Norris and a flock of helpers do-si-do around a crowded kitchen, preparing ramen noodles and hot broth donated by Shantel Ringler Grace, ’02, co-owner of the Mass Street restaurant Ramen Bowls. The vibe is welcoming, convivial and informal: Diners line up to serve themselves from steaming pots and then sit at big tables or join in a Smash Bros video game tournament underway in the next room. The suggested donation is $2, but it’s understood, not mentioned. Students can eat as much as they want and take to-go boxes when they leave. The setup turns a traditional helping model on its head: By creating a lively community dinner where all are welcome, organizers of Ikigai (a Japanese concept meaning “reason for being”) hope to destigmatize the soup kitchen.

“Some people don’t take advantage of resources because there’s a shame factor,” Grace says. “Our idea is, if you want to put a couple bucks in the donation box, that’s great. But nobody’s sitting here taking money. Just help yourself.”

As Emily Doffing worked to make a life at KU during her freshman year, part of her goal was to find a church. At LCM she discovered a congregation that not only makes students feel at home with the help of food (the ministry serves around 150 students a week at three different meals), but also talks about food insecurity and educates students about campus and community resources to fight it. That mission was driven largely by students, Norris says. “We had always done free meals, but the students were the ones who said, ‘Let’s focus this on food insecurity; let’s take this seriously as a way of giving back to campus.’” Doffing and a friend who also struggles with food insecurity made the Thursday dinners at Westwood House a regular night out.

“I remember we were standing in line for ramen, and I saw on the bulletin board an article about food insecurity,” Doffing recalls. “I was struggling with a lot of misconceptions: that it’s only a few college students, or it’s normal or there’s not a lot of resources in Lawrence. I read the article, and it had phone numbers and addresses and statistics. I felt all those misconceptions literally being eliminated and being replaced with information that gave me hope and also got me on the right track to start eating regularly and healthy. And that carried through to all the different things in my life such as academics and having energy and feeling good again.”

Around the room, diners dig in to fragrant bowls of ramen heaped with fresh vegetables. Several report attending the Veggie Lunch at Ecumenical Campus Ministries earlier in the day; others say they use the Free Food Finder in the Alumni Association app to locate free meals on campus. One is a recent graduate who just earned her second KU degree, a master’s in social work. Like Doffing, she came to KU with the help of a Pell Advantage grant, but as a freshman new to dorm life she bought the cheapest campus dining plan, which provided 10 meals a week.

“I had to be strategic,” she says. “I would eat my morning meal around 10 a.m. and then not eat again until after 5. I basically ate two meals a day freshman year. I had a friend with an unlimited meal plan who gave me meals. That’s how most people get through it—friends and roommates.”

A young woman from Wichita, who describes herself as “a broke college student,” says she eats here every Thursday night, “because it’s always my last meal before payday and I usually need the free food.” A young man from Peru who frequently takes advantage of free fare at campus events says he likes Ikigai “because it’s good, fresh food. If it was just more pizza, I probably wouldn’t come.”

Indeed, this is not their parents’ ramen. The scratch broth and handmade noodles ($12 a bowl on Mass Street) are an entirely different animal than the brittle, sodium-laced dehydrated bricks that cost a quarter a pack in the instant food aisle at the grocery store.

Almost every interview for this story (and a high percentage of the comment sections for online articles on the topic) eventually came around to what Ike Uri calls “the classic trope” about college and food: Students are supposed to live on ramen. (Or macaroni and cheese. Or pizza.) It’s what you do. It’s what we did. They’ll be fine.

“People tend to say, ‘Oh, well, it’s not a big deal; I ate ramen when I was a college student and I got by,’” Stacey Swearingen White says. “Really? Is that the best we can hope for our students? Because there’s also a health-eating connection that can affect academic performance—as well as the fact that higher education is so much more expensive than it was when I got my college degree, for example, that it’s just a very different situation.”

One of the problems with this myth “is the assumption that what’s happening today is the same as what happened 20 years ago or 40 years ago,” says Norris, who has been the campus minister at LCM for two decades. “I’m old enough that I had a classmate who worked his way through an expensive private college; what students can make in a summer now does not come close to covering costs. There’s a huge difference in the affordability of higher education. Obviously that’s changed. So somebody who says, ‘Well, we ate ramen, they can eat ramen, everything is gonna be fine,’ misses that change in our culture.”

It’s a change that has rippled throughout all levels of University administration, including the very top. In remarks made to the Student Senate earlier this year, Chancellor Doug Girod noted that state appropriations made up 17% of KU’s total budget in fiscal 2018, compared with 27% in 2008. In 2018, tuition and fees accounted for 23% of the budget.

“I think now we have the knowledge to understand the mind-body connection to academic success,” says Jennifer Wamelink, associate vice provost for student affairs, who assisted both Uri and White with their surveys. “If you’re not getting the appropriate nutrients, you’re not best positioned to do well academically. So I think our thinking has changed, but also the affordability of college has changed. If you’ve listened to the chancellor’s remarks about what percentage of their education is now being funded by our students rather than the state, if you just look at pure percentages, our families are carrying a higher load financially that’s outpaced federal aid. Many of our students have pretty substantial gaps between what they’re receiving in aid and what it actually costs to attend KU.”

Young people, of course, are always ignoring good advice on diet, sleep, exercise and a host of other habits and practices adults see as counterproductive. All part of growing up. But it’s different when the decision to skimp on food is a necessity rather than a choice.

“It’s always been a thing that skipping meals or living on ramen and pizza is tied to what it means to go to college,” Dana Comi says. “But it’s not healthy, it’s not sustainable and I think it gets romanticized. There’s a big difference between eating a ramen packet at 2 in the morning because you don’t live with your parents anymore and eating it because you have a real lack of access to anything nutritional.”

“I know if I don’t eat breakfast or don’t have something in my system, I’m going to be thinking about it all day and I can’t focus. I should be listening in class, but I’m planning what am I going to eat after class is out.”

“I brought this on myself; I’ll figure something out,” Emily Doffing remembers thinking during her freshman year, when food insecurity for her was at its worst.

After paying bills, she often had little money left for food. A friend who got sick and went to Watkins Health Service for treatment found out later that the student health center doesn’t take Medicaid; the resulting medical bill wiped out the woman’s savings. Another friend was blindsided by an expensive textbook needed for class. A week with one less shift on the work schedule, a surprise car repair, or an unexpected spike in the heating bill could wreck a budget already on the tightest of margins.

Doffing knew nothing about the Campus Cupboard or Just Food, the community food bank that keeps the student cupboard stocked. But if she had, she says, she’s not sure she would have grabbed those lifelines back then.

“When you’re a freshman and everything is new and scary and you don’t know anyone or anything, it’s not easy to talk about stigmatizing or difficult things you’re going through,” she says. “I didn’t know food insecurity is as prevalent on campus as it is. I thought struggling with food was something particular to me because of low income, and I didn’t know that Lawrence has so many resources that so many people do use. I had the misconception that I can just power through on my own, the pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps that society tells us for so many things. But it’s OK to get help sometimes.”

In her focus group research, Stacey Swearingen White determined that only 12% of students experiencing the highest level of food insecurity were accessing food assistance resources of any kind.

“You might think, ‘My gosh, how are they not?’” she says. “If they are in this much need, why aren’t they?”

The answer, for many, is shame.

“There’s just a really large social stigma that’s been put on people for having need in this regard,” White says. And if that’s felt by society at large, it’s even more acutely felt by college students. The message students hear is, You have enough money to go to college, you should be doing OK.

“That filters down. The students will say, ‘Oh, well, those [resources] aren’t really for me; those are for people who really need it.’ So that stigma, that bad stereotype of students subsisting on ramen and popcorn, extends to those experiences. It’s like that’s how it’s supposed to be.”

“Students know they are struggling, but being here at the University in and of itself is seen as a privilege,” Wamelink says. “And so I think students perceive things like SNAP benefits or the community cupboards as, ‘I’m not struggling enough; there are people hurting worse than me, and those resources are for them and not for me.’ Even though that student is not eating three meals a day.”

Gratitude is, indeed, a common theme: Almost every student who discusses food insecurity mentions how grateful they are to be at KU, how lucky they feel to be getting a scholarship or Pell grant, because otherwise they couldn’t afford college.

Recent data on college food insecurity nationwide suggests that these aren’t entitled snowflakes whining for a handout, nor are they participants in some time-honored rite of passage, a harmless character-building experience that teaches college students fortitude and self-reliance.

“That’s a pretty classic discounting of an experience that is inherently doing a lot of violence to the individuals who are experiencing food insecurity,” Uri, now a PhD student at Brown University, says of the mythology that normalizes hunger and stigmatizes food assistance. “Their narratives aren’t being taken seriously here. I would just hope that we could aspire to something a little bit better than that for our students. And I know, personally, if I subsisted only on ramen, I wouldn’t last very long.”

“It’s unfortunate that we can just look at it that way,” White says. “That doesn’t seem good enough, I think, to look at it that way when students have other stresses and the average student at KU works 20 hours a week. It’s not like they’re sitting around bemoaning that they have to have another bowl of ramen. They’re struggling. And that’s something we should all be concerned about.”

In September 2018, the Campus Cupboard moved from Westwood House to its current location in the Kansas Union. What had started as an ad-hoc effort initiated by students and hosted by near-campus spiritual centers was, for the first time, actually on campus.

That evolution is a prime example of the University’s response to food insecurity, which has been driven largely by students, but increasingly backed by administrative buy-in.

“Our students were telling us this is a need,” says Jennifer Wamelink, of student affairs. “That’s really where it started.”

In year one, the cupboard logged 2,657 visits; 92% were students and 8% were staff or others. (See “Food Issues also affect staff”.) Of the 449 verified unique student users, 89.3% returned to KU or graduated by fall 2019. Through this September, Wamelink says, the Campus Cupboard has already logged 508 visits.

“We definitely have students coming in who are struggling to make ends meet, and this is helping them round out their nutritional and caloric needs,” Wamelink says. “We know we’re hitting a need.”

Largely responsible for the move were Katie Phelan, h’14, g’16, and Insia Zufer, c’18, who in 2017 served as co-directors of the KU Center for Community Outreach. The student-led organization was founded in 1990 to help KU students find community service opportunities in Lawrence, and the Campus Cupboard is one of a dozen programs CCO oversees. The future doctors—Phelan is in medical school at KU, Zufer at Johns Hopkins—worked with Student Senate and KU administrators to secure funding and space for the cupboard on level four of the union. Student body president Maddy Womack, c’18, and vice president Mattie Carter, c’18, j’18, made the cupboard a top priority for their term in office.

Phelan and Zufer credit Ike Uri’s survey for spurring an institutional response to an issue that had not been targeted in an organized way.

“The research kind of revealed an underlying problem on campus with food insecurity that students were experiencing that I think previously had been very under-recognized and not talked about much among administrators,” Phelan says.

Phelan and Zufer joined a new effort headed by the student affairs office, the Food for Jayhawks committee made up of staff, faculty, students and community members. The group’s main charge is ending food insecurity and hunger on campus by improving student access to healthy food and food resources with collaborations among KU departments and community agencies.

Wamelink says Kelsey Fortin, the student in health and exercise science who also worked on White’s hunger survey, first opened her eyes to the need for a more formalized workgroup three years ago.

Fortin had been working at Harvesters Community Food Network, a regional food bank that serves 26 counties in northeastern Kansas and northwestern Missouri, when she was hired as a health educator at Watkins Health Center in 2013. Nutrition was one of her topic areas. She met with students in one-on-one sessions to help them set personal goals such as losing weight, gaining weight, or improving nutrition. “That’s where those conversations would come up,” Fortin says, “and individuals would note, ‘Well, the reason I couldn’t get my requirements for fruits and vegetables for the past week is I don’t have the money.’”

Fortin joined KU Fights Hunger, which had grown out of a series of campuswide food drives that started around 2008. (The food drives are now conducted during the month of October and for a time were a major focus of the yearly Homecoming celebration organized by the Alumni Association.)

“The whole group really started as an effort to benefit Just Food,” the Lawrence food bank directed by alumna Elizabeth Keever Schooler, c’10, Fortin says. “But as students got involved, there started to be this connection about maybe there’s a need for food resources for students on campus.”

Around the same time, the first campus food pantry started at ECM, an outgrowth of the ministry’s weekly Veggie Lunch program. “So there were students in that space at ECM who were saying, ‘Hey, we’re students and there’s an issue of access to food from our perspective, too,” Fortin says.

Eventually, student participation dropped off, and Fortin, by then an executive member of the group, and others decided that a more formalized committee of staff members would help the University respond to the issue. KU Fights Hunger morphed into Food for Jayhawks.

“I think we worked really hard with KU Fights Hunger to engage folks and often felt like we weren’t making a lot of progress,” says Jeff Severin, c’01, g’11, director of campus planning and sustainability and a member, at various times, of both committees.

While KU Fights Hunger did great work to engage and educate the community about food insecurity on campus, Severin says, it was “really just a loose organization of folks who were passionate about the issue.

“The fact that student affairs took this on and has been coordinating it for the past couple of years really indicates that they see this as something that is critical to student success and that needs that level of attention, that it’s not just something dedicated volunteers are trying to address, but that departments within the University are committing their time and resources,” Severin says. “That was a really important and positive move that’s helped engage an even broader audience in the conversation, in looking for ways to address the issue, and I think in helping overcome the myth of the poor, hungry college student—recognizing that’s not acceptable and we need to be doing more on our campus.”

Some efforts, like moving the Campus Cupboard to the Kansas Union, have succeeded. Locating the cupboard on campus, in a building that’s student-focused, sends a message that it’s a resource students should use, advocates say. Other moves, like an effort to establish a meal plan system similar to the national Swipe Out Hunger campaign, which allows students to donate unused campus dining funds to fellow students in need, have not taken off at KU. Student affairs launched a Food For Jayhawks meal plan, which provides $425 that’s loaded on a student’s KU card to use at campus dining halls. But a campaign last fall to raise money for the plan through Launch KU, a crowdfunding effort from KU Endowment, met only 60% of the $25,000 goal.

“It wasn’t super-successful,” Wamelink says, “and I think some of that is disbelief or shock that this is really an issue for college students.” As a result, the program is now available only by referral, and it has helped fewer than 10 students.

There are various “pockets of emergency aid money” around campus intended to help students facing all sorts of barriers to their success at KU, Wamelink notes, and a new website, help.ku.edu, is meant to make it easier for students to find those resources. And some academic units do what they can to help. The English department, Dana Comi notes, maintains a food pantry for graduate students stocked by faculty members.

“We have a lot of work to do,” says Kelsey Fortin. “I think our pantry efforts are pretty strong, but I still see us as behind the curve of some of our peer institutions.” Kansas State, for example, has long had a staff member dedicated to food insecurity and recently hired a second. “That’s certainly one of the recommendations that came out of our research,” says Fortin, who’d also like to see additional studies on the extent of the problem on campus and more training on money management, grocery shopping, meal planning and other life skills that might help students battle food insecurity.

In the focus groups that she hosted with White, she recalls a student reporting that she’d been diagnosed as anemic because of poor diet.

“We’re seeing direct negative health outcomes as well as negative academic impacts from students being in this food insecure state,” Fortin says. “To me it’s a wake-up call to the University; if we say one of our big charges is overall well being of the individuals here, and we want to keep our retention and graduation rates high, well, we need to recognize that food insecurity is a factor that’s negatively impacting those things.”

Emily Doffing found ways to stabilize her food supply. Now a junior majoring in psychology with minors in political science and French, she works two jobs and volunteers at Headquarters Counseling Center.

“I do appreciate what KU does with things like the Campus Cupboard,” which she uses as needed, “but I also know there is more KU can do.” One thing she’d like to see: more up-front communication to first-year students on the availability (and cost and usage limits) of food, health, mental health and academic support services. Rather than rely on students to face down the stigma of asking for food assistance themselves, she thinks the University can send a message: We know food insecurity is an issue and we’re here to help.

“When it comes to someone’s well-being, I don’t really see the question as, Are we doing enough?” Doffing says. “The question should be, Are we doing all we can?

Community Food Resources

Campus Cupboard, food pantry for KU faculty, students and staff

Level 4, Room 132 Kansas Union

785-864-4060

Just Food, Douglas County food bank

1000 East 11th St., 785-856-7030

Westwood House, student meals and food pantry

1421 W. 19th St., 785-550-6560

Ecumenical Campus Ministries Veggie Lunch

1204 Oread Ave., 785-843-4933

Lawrence Interdenominational Nutrition Kitchen (L.I.N.K.), free homemade meals

First Christian Church

10th & Kentucky, 785-331-3663

Ballard Center Mobile Food Pantry

Douglas County Fairgrounds

785-842-0729

Department for Children & Families, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

1901 Delaware St., 785-832-3700

Jubilee Café, free breakfast served restaurant-style

946 Vermont St.

jubilee@fumclawrence.org

Trinity Interfaith Food Pantry

1027 Vermont St., 785-843-6166

Lawrence Emergency Assistance Center (EAC)

1525 W. 6th St., 785-856-2694

Salvation Army

946 New Hampshire St., 785-843-4188

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC)

Food vouchers for pregnant women and families with children under 5

200 Maine St., 785-856-5350

Food issues also affect staff

In spring 2019, the Office of Diversity and Equity in collaboration with the Staff Senate surveyed all faculty and staff on food insecurity and other issues.

“The survey asked whether folks felt they weren’t able to eat balanced meals, if they don’t have money to buy food at the end of month, or if they use local resources for clothes and other things,” says Jeff Severin, co-chair of Staff Senate’s diversity and inclusion committee. “We were trying to gauge how often that happens and do they have to choose between paying for food and basic living costs.”

About 20% of the 500 respondents indicated they often or sometimes experience food insecurity.

Severin cautions that the survey, which was distributed via email and conducted online, was not a random sample and could be skewed toward those who are “looking for a way to share their need” or those who have the greatest access to a computer during the day. But the numbers are not wildly out of line with other local surveys.

“In comparison to the number of students and the number of people within Douglas County generally who experience food insecurity, it wasn’t surprising,” Severin says. “I feel like there are certain areas of campus where our salaries aren’t meeting a living wage, so it doesn’t surprise me.”

Participant comments clustered around several themes, including:

• Staff in single-income households are more likely to struggle with food insecurity.

• Many dual-income families noted they are a job loss away from food insecurity.

• There is broad frustration about low/stagnant wages and wage inequality at KU alongside rising health care, child care, transportation and housing costs.

• Some families are debt-financing food security (with credit cards) while others struggle with high household debt obligations.

• Shame was identified as the major barrier to accessing support.

• Those who need access to food support may not be aware of on-campus resources.