An Army Afire: Book traces military’s about-face on ‘race consciousness’

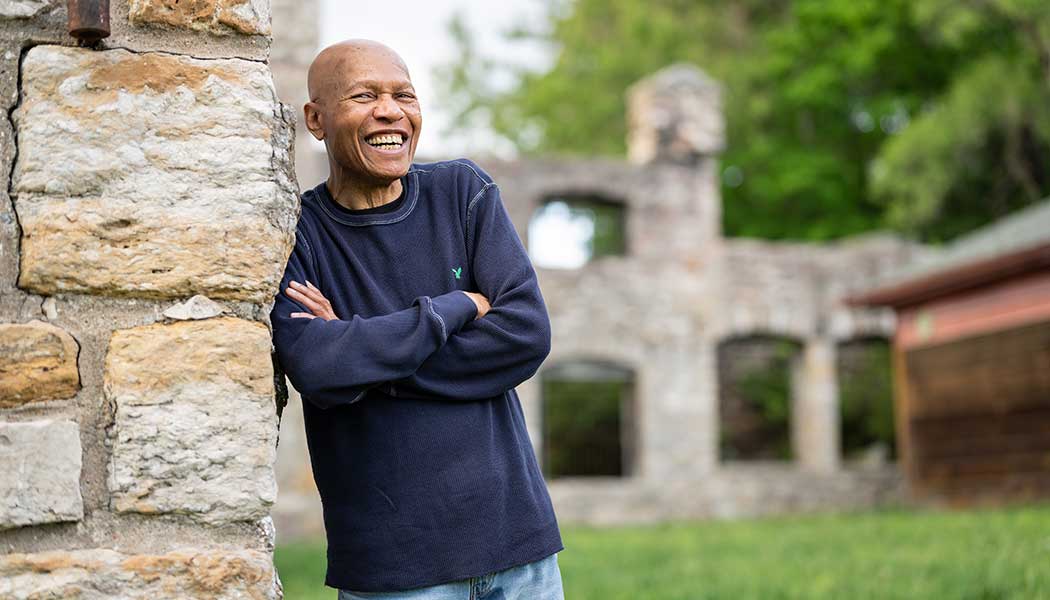

KU professor Beth Bailey’s Vietnam-era history shows that confronting conflict, rather than denying it, was key to Army’s progress on integration.

As the U.S. military grappled with an intractable war in Vietnam that grew more and more unpopular the longer it dragged on, one branch of the armed forces was also battling a war within its ranks—“the problem of race,” in the Army’s phrasing, that put white and Black soldiers into conflict with one another.

In the two decades after President Harry Truman ended segregation in the armed forces with Executive Order 9981 in 1948, the nation’s integrated military came to be viewed as positively progressive, especially when compared with the violence and vitriol inflicted by civilian society on the Civil Rights Movement. In 1966, Time Magazine declared that, “despite a few blemishes, the armed forces remain the model of the reasonably integrated society that the U.S. looks forward to in a new generation.” A Washington Post headline from the same year reflected an assessment shared by many Black leaders: “Army Cited as Example of Integration’s Success.”

As Beth Bailey writes in An Army Afire: How the US Army Confronted Its Racial Crisis in the Vietnam Era, that all changed by 1969, when the Army’s chief of staff and its secretary “put race second only to the war itself in their catalog of concerns.”

A Foundation Distinguished Professor in KU’s history department since 2015, Bailey has written extensively about the military, war and society. In An Army Afire, she identifies the tumultuous year of 1968 as a turning point in commanders’ awareness of the growing anger and resentment of Black soldiers who felt unfairly treated by the military and by the communities that surrounded Army bases at home and abroad. She highlights two events that proved the rank and file did not view the Army as the progressive haven trumpeted by the Army brass, mainstream media and community leaders.

On Aug. 29, Black soldiers imprisoned in the stockade at Long Binh, a large U.S. base in Vietnam, seized the jail for several days, burned buildings, and beat guards and other prisoners, killing one. A few weeks later, in mid-October, Maj. Lavell Merritt, a veteran infantry officer nearing mandatory retirement, interrupted the official military press briefing in Saigon to pass out a statement that called American armed forces “the strongest citadels of racism on the face of the earth.”

Bailey traces how top commanders, spurred by these and other worrying incidents, gradually came to see that “racial violence, racial discontent, racial tension, racial discrimination, and flat-out racism” presented a fundamental crisis that threatened the Army’s core mission of national defense. She chronicles, in granular detail, how the institution turned its massive bureaucracy to evaluating, defining and solving the problem—often showing, in the solutions proposed, a remarkable creativity and a surprising willingness to challenge Army tradition.

Embracing the methodology of the human potential movement then in vogue, bases held rap sessions and encounter groups to foster communication between Black and white soldiers. After its chief of staff mandated the training in 1969, the Army developed “the world’s largest race relations education system in the space of seventeen weeks,” Bailey writes, “a minor miracle.”

By the 1970s, PXs were stocking Black hair products, and commanders were encouraged to tolerate the cultural symbols (Afro hairstyles, soul bracelets, Black Power insignia and dap handshakes) that soldiers claimed as part of their Black identity. Some cultural accommodation turned out to be only a temporary reaction to crisis; other changes were permanent. By 1972, education on race relations and Black history and culture was integrated into Army training at all levels. “This was no longer a response to crisis,” Bailey writes. “It was a part of army life.”

The transformation An Army Afire documents is an institutional shift in philosophy from “race blindness” to “race consciousness.” A common refrain of the Vietnam-era Army, “I only see one color—olive drab,” was replaced by a more nuanced understanding of individuality and group pride spearheaded largely by Black enlisted men, but also driven by a broader generation gap that pitted old against young regardless of race. Summing up one argument, Bailey writes, “Contemporary youth—Black and white alike—wanted their respective ‘identities’ recognized.”

The final chapter of An Army Afire asks a basic question: Did it work? If the goal was to restore stability and bolster the Army’s readiness to defend the nation, Bailey concludes, the decision to hear out its critics, honestly assess its shortcomings, and ask hard questions about the effectiveness of a “color-blind” approach to race clearly succeeded. If the goal was to create racial equality in the Army, results were more mixed. Much has changed, she writes, but much remains to be done.

The racial tensions Bailey reexamines in this important work resonate in our own divided era, when the teaching of history is a battleground in a different kind of war. Had those tensions been allowed to fester unexamined until they exploded, the effects on a fighting force (and a society) already neck-deep in a difficult and divisive conflict might have been catastrophic. Instead, by facing America’s historical and cultural legacy of racism, slavery, segregation and prejudice, one of the country’s most conservative, tradition-bound institutions found itself up to the hard task of grappling with “the problem of race.” From the vantage of these current turbulent times, that seems a miracle more major than minor.

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photo by Steve Puppe

/