Elizabeth Watkins: A woman in full

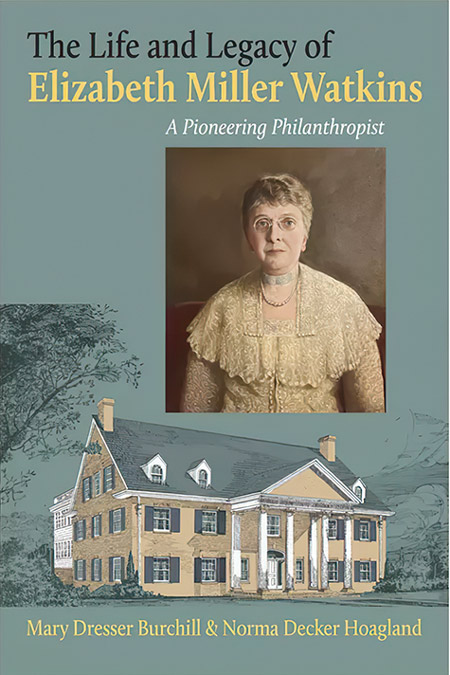

New biography brings to life the remarkable Elizabeth Watkins, a pioneering KU philanthropist.

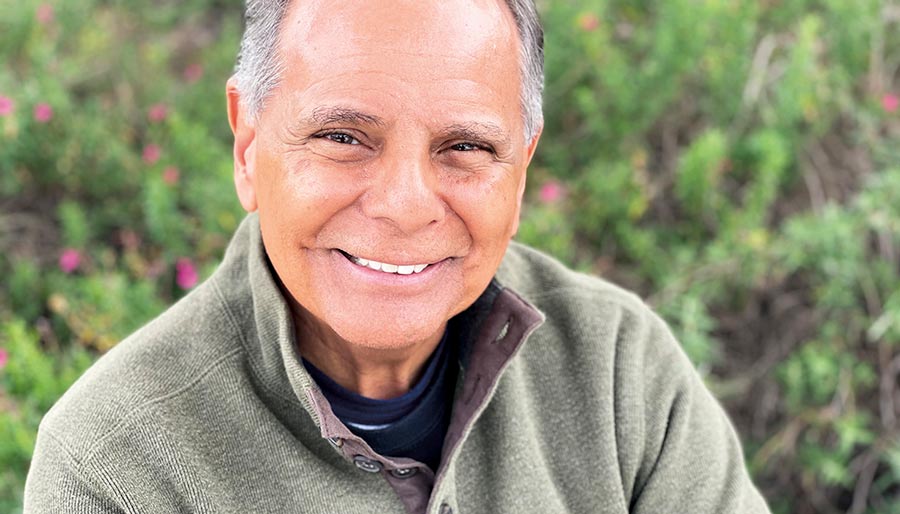

Mary Dresser Burchill’s parents moved from Lansing to Lawrence in 1922, when their first child was born, because, Burchill says, “They knew that they weren’t going to be able to afford to send their children off to college, so they thought, ‘We’ll just move to the town where the school is.’” So Mary and her siblings lived at home while attending KU, “and that was fine,” she recalls.

Burchill, c’62, associate director of KU’s law library from 1979 until her 1995 retirement, landed a student job that she loved in Watson Library, and, given the proximity, grew fond of the chancellor’s stately residence, known as The Outlook. She also became vaguely aware of the matriarchal figure who had donated that property—along with two neighboring scholarship halls—to the University, and who had bequeathed to Lawrence what for decades served as City Hall, the former Watkins National Bank at 11th and Mass.

For Burchill, Mrs. Elizabeth Watkins was a generous if ghostly grande dame whose husband had generated enough wealth for her to live out her final years in fine style while also caring for the needs of students.

The Elizabeth Watkins who emerged after years of research, however, was a woman of far more depth, drive and determination. The Life and Legacy of Elizabeth Miller Watkins: A Pioneering Philanthropist, by Burchill and Norma Decker Hoagland, tells, in far greater detail than previously known, the story of a singularly remarkable woman.

“It was an amazing life,” says Hoagland, c’75, a Watkins Hall alumna and author of what had been the most complete history of Mrs. Watkins’ legacy, 2016’s Watkins and Miller Halls. “Her gifts are still giving to the University, especially the scholarship hall system. She started the whole thing.”

With the breadth of their new biography—including particularly welcome insights into high finance of the late 19th century—Burchill and Hoagland reveal a complex, nuanced picture of Lawrence’s most prominent couple.

Among other towering achievements, JB Watkins brought the rice industry to Louisiana and essentially created the city of Lake Charles. The authors tell the story of Elizabeth Miller’s unlikely relationship with her employer by emphasizing the couple’s accomplishments as a personal and professional team, without overly stressing what Hoagland describes as the “prurient aspects” of their lives, including JB’s alcohol abuse and Elizabeth’s willingness to join him on frequent and extended business trips, without a chaperone, for many years before their marriage.

Shortly after they wed in 1909, Elizabeth and JB began developing a 5-acre tract known as Robinson Farm, which Watkins had purchased more than a decade earlier. Construction on the Neoclassical Revival estate, with views of both the Wakarusa and Kansas river valleys, began in 1911, and in 1912 the couple finally had their dream home.

After JB’s death, in 1921, Elizabeth inherited, according to Burchill and Hoagland, an estate estimated at $2.4 million; at her death, in 1939, the estate, even after two decades of exceptional generosity, was worth about $3 million.

“She built, equipped, and furnished Watkins Hall, Lawrence Memorial Hospital, Lawrence Memorial’s nurses’ home, Watkins Memorial Hospital, Miller Hall, Watkins Memorial’s nurses’ home, and the guest cottage, not to mention additions to several of these projects,” the authors write. “There can be no doubt she was a successful businesswoman, ahead of her time. She not only survived the Great Depression of the 1930s, but came through with more money than when she started.”

Hoagland, a Leavenworth rancher, notes that 2026 will mark the centennial of Mrs. Watkins’ centerpiece gift, Watkins Hall, and that one University official has suggested to her that a statue could be in the works, noting that its ideal placement would not be near The Outlook and scholarship halls, but rather on Jayhawk Boulevard, where there are no public memorials to a woman.

“Wouldn’t that be fun?” Hoagland exclaims. “Elizabeth’s message to everyone would be to prepare yourself for life. Get your education and value it and your educators. You never know what life has in store for you—look at the turn her life took!”

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photo by Steve Puppe

/