Teachers adapt courses for online delivery

In a typical year, Laura Diede and her 10-person staff help 150 instructors create videos, record lectures and find other ways to put class lessons online.

After KU announced in March it would transition all classes to remote-learning formats to protect students, faculty and staff from COVID-19, “It’s basically everyone who needs to do it,” says Diede, c’03, g’09, director of the Center for Online and Distance Learning (CODL). “So we’re helping everyone. It’s an explosion.”

The huge task of moving thousands of courses from classroom to computer screen fell to CODL, the Center for Teaching Excellence (CTE) and KU Information Technology. News of the plan reached Diede in early March, and by the next week—spring break—the three partners “were already in full transition mode,” Diede recalls.

Andrea Greenhoot, director of the Center for Teaching Excellence, says CTE drew on its mission of encouraging professors to explore innovations in course design and teaching. What had once been a measured, even reflective process became an urgent scramble with an impossible-sounding deadline.

“We had to recognize this is not the normal situation” for online course development, Greenhoot says. Professors had already put lots of thought into designing classes for in-person delivery, and now they had only a couple of weeks to move online. The emphasis was on easily translatable solutions that wouldn’t require tons of new technology or whole-scale redesign.

Among the first moves was gathering faculty members who already have experience with remote technology or course design—“power users of online learning,” Diede calls them—to start the Faculty Consultant Network (FCN).

“They serve as thought partners for their faculty colleagues,” Greenhoot explains. “It’s discipline-embedded expertise and consultation for faculty trying to figure out what to do with some of the thornier issues they’re encountering in their classes. Things like, what do engineers do with their typical exam format? What are the options for remote delivery? What do you do about labs?”

CTE, CODL and KU IT realized early on that faculty and adjuncts were thrown off balance by an unprecedented public health crisis. The same could be said for students.

“The student experience right now is very different from what you would normally expect from students who enroll intentionally in online classes,” Greenhoot notes. “Many are not prepared; they’ve never engaged in online learning; they don’t have the technology they need and they are stressed by all the other things going on related to COVID, including new work and child-care responsibilities. And actually, that is also true of our faculty.”

Lisa Sharpe Elles, assistant teaching professor of chemistry and an FCN member, has used “lots of technology” in her 10 years in the classroom, but she had never taught a course completely online. Now she teaches two: a general chemistry class for science majors with 270 students, mostly pre-med and pre-dental, and an intro class with 170 students, mostly pre-nursing.

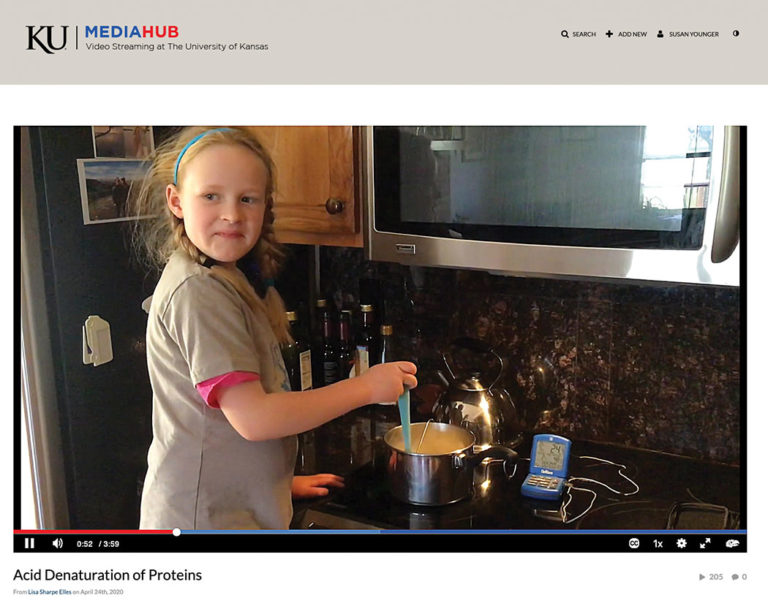

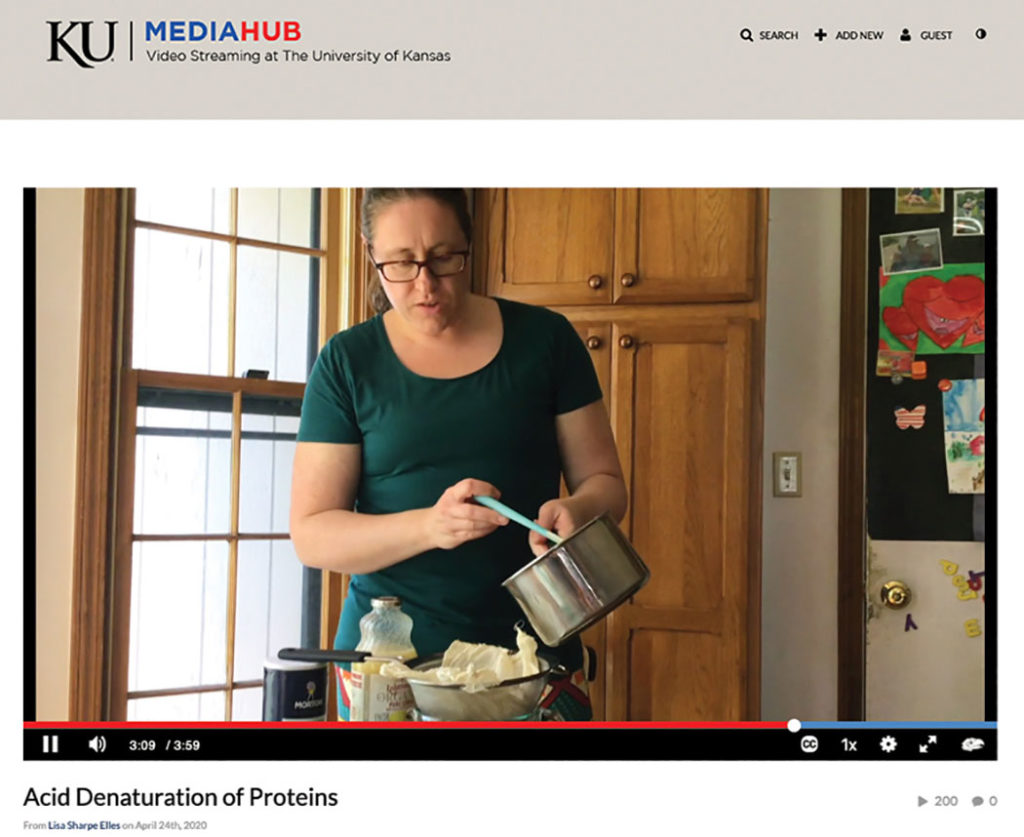

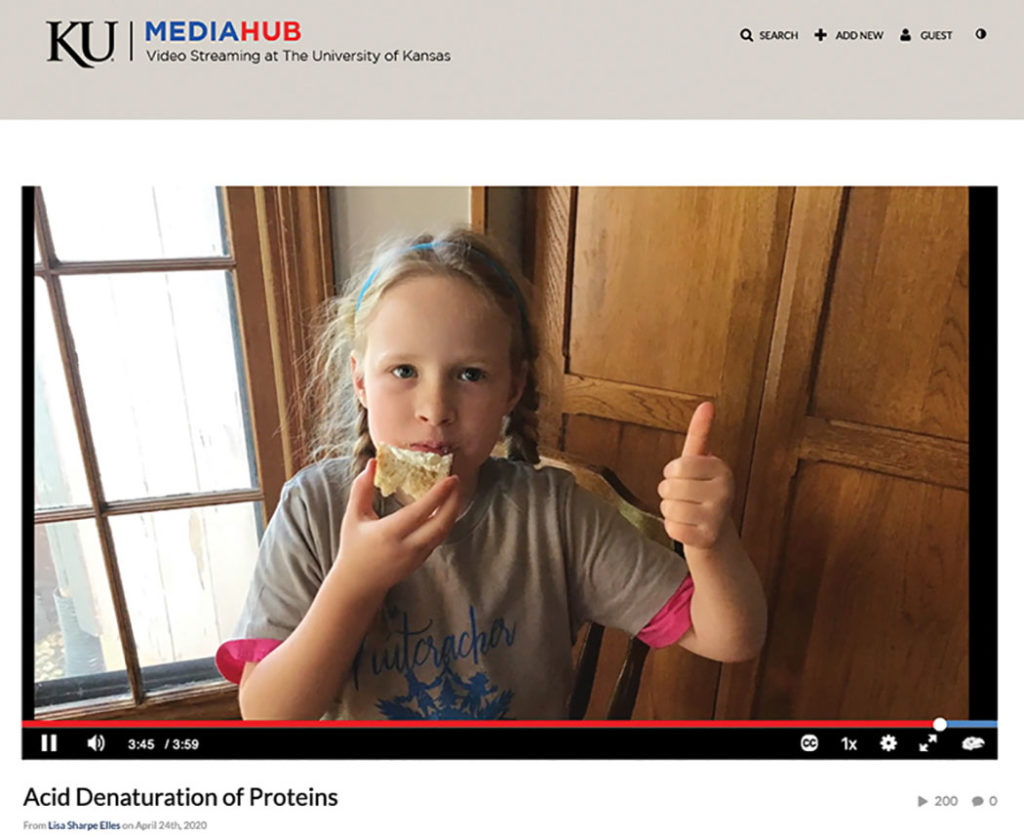

In addition to recording six lectures a week for students to watch at their convenience (what online course designers call asynchronous delivery), Elles also videotaped lab assignments starring her two elementary-school-aged children, who have their own schooling (and entertainment) needs Elles must attend to while working from home.

The hands-on projects keep her kids occupied and engaged in their own science learning, while freeing her to get behind the camera. The lessons also allow her to use the one lab she’s fairly certain her students can access: a kitchen.

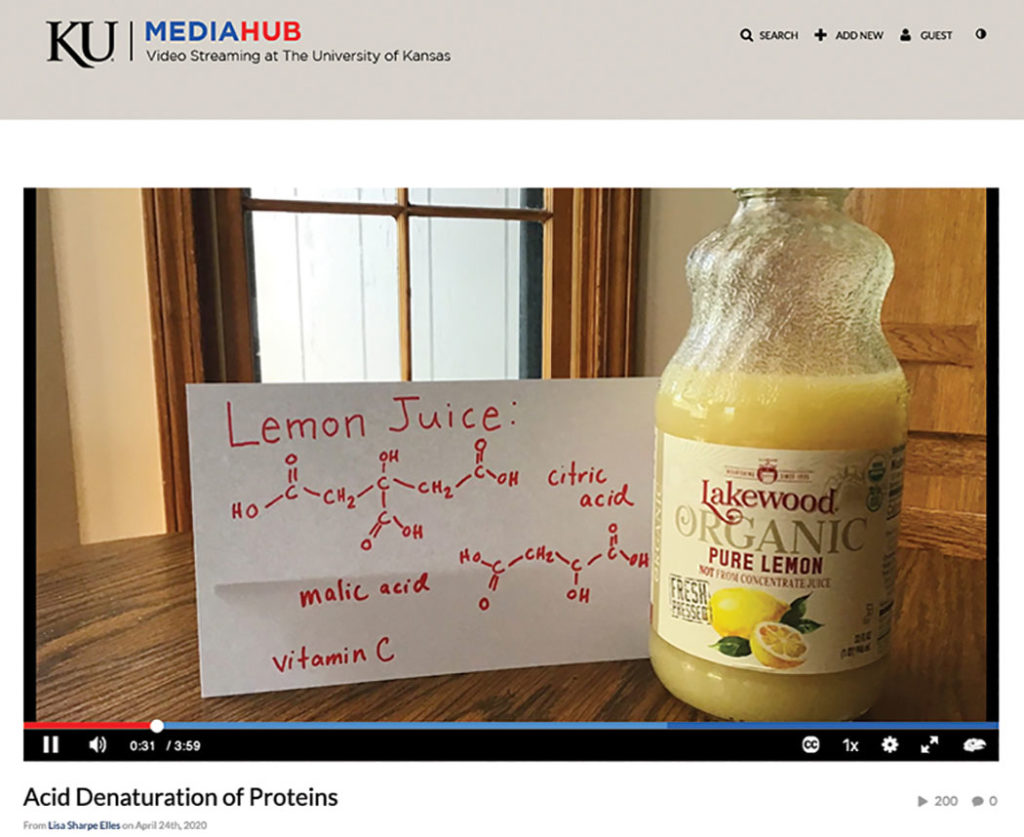

“They aren’t going to remember every bit of chemistry they learn,” Elles says of her intro students, “but I want them to have an understanding of science and be able to think critically and see science in the world around them. Cooking chemistry teaches them about biochemistry and gives them an opportunity to actually do some labs in the kitchen.”

For a lesson on acid denaturation of proteins, she enlisted her 6-year-old daughter, Roslyn, to demonstrate cheesemaking. Not only did the demo stand in for Roslyn’s canceled science fair, but it also might prove more engaging for her own students, Elles believes, while helping her connect personally with people she feels distanced from now that she doesn’t see them in class three times a week.

“The point is, ‘Hey, I’m a person, I have kids and they’re taking up a lot of my time, too,’” Elles says. “I’ve encouraged students throughout the semester to share what they learn with their families. If they’re at home and learning, they can do that, which also helps those lessons set in a little better.”

Science labs are only one example of instructional methods dramatically changed by the transition to distance learning. Professors in theatre, film, music, dance and other disciplines hurried to find new ways to instruct and help students collaborate and share their work. Plays, recitals, internships and student teaching rotations have been canceled, leaving fundamental gaps in outside-the-classroom learning that’s essential to many areas of study. For programs like architecture, which stresses a hands-on approach, the challenge can seem existential.

“We do design-build, we do study abroad, we do community engagement, we do internships,” says architecture professor and FCN member Shannon Criss. “It’s what KU architecture is known for, and I do think that’s why students come to KU, for these real-world experiences. But all that is on hold now; we’re not able to what we do best.”

Some teachers, like some students, are more tech-savvy than others; all are learning the limitations of the screen.

“Sitting in front of a student, demonstrating drawing—that’s not as easily done through the screen as it is one-on-one at their desk,” Criss says. On the other hand, change has forced everyone to rethink old strategies.

“Before, students would just show up with their designs, and you’d pin it up and look at it,” she says. Now Criss has them produce brief slideshows explaining their work, which gets shared in small peer groups and reviewed by Criss. “They’ve gotten so much better at presenting, because they’ve practiced three times a week; you can just see the progression in their work.” The video format also allows her to tap outside expertise. “I can invite alumni and professionals from New York and L.A. to review student work, which I could never do previously. We can do interdisciplinary work with community members or people in public health. It enriches the student experience.”

The bottom line, Greenhoot and Diede agree, is that disruption is forcing teachers to innovate, and that can be a good thing.

“Teachers have been as nervous and anxious as students have,” Diede says. “Most didn’t sign up to be online instructors, just like most students didn’t sign up to be online learners. But everyone has risen to the occasion.”

With all summer classes online and some form of on-campus operations planned for fall, teachers still feel uncertainty and pressure. Some, citing health conditions or age, worry about returning to the classroom before the coronavirus is conquered. Others wonder if large classes are compatible with the social distancing public health experts say will be necessary far into the future.

“We gave each other grace in the spring because we had to,” Criss says. “As we move forward, the pressure is on to do better. Can we make this disruption an innovation moment? Because where we were is probably not where we’re ever going to be again.”

As the University adapts to the rapidly changing environment, KU leaders will continue to update guidance in a document first published May 20: “Re-opening of KU Campuses in the Era of COVID-19.” For the latest information, please visit coronavirus.ku.edu.