Make the Dream Work

When Barney Graham set off in that hopeful way that teenagers tend to do, he launched himself from his family’s Paola farm in a brand-new 1971 Mustang fastback, pure American muscle for a dashing young man hitting the open American road.

The panache with which Graham roared off on life’s great adventure was warranted: Why not hop behind the wheel of a Mustang when you’ve ridden a real one, bareback, in an actual rodeo?

His beloved silver sports car launched Graham on a long trajectory that took him from Rice University, in Houston, to the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, Maryland, where in early 2020 he led a team of brilliant, brave, determined researchers on a quest to save millions of lives by creating the structure underpinning the Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines, described by The Atlantic magazine as “the two fastest vaccine trials in the history of science.”

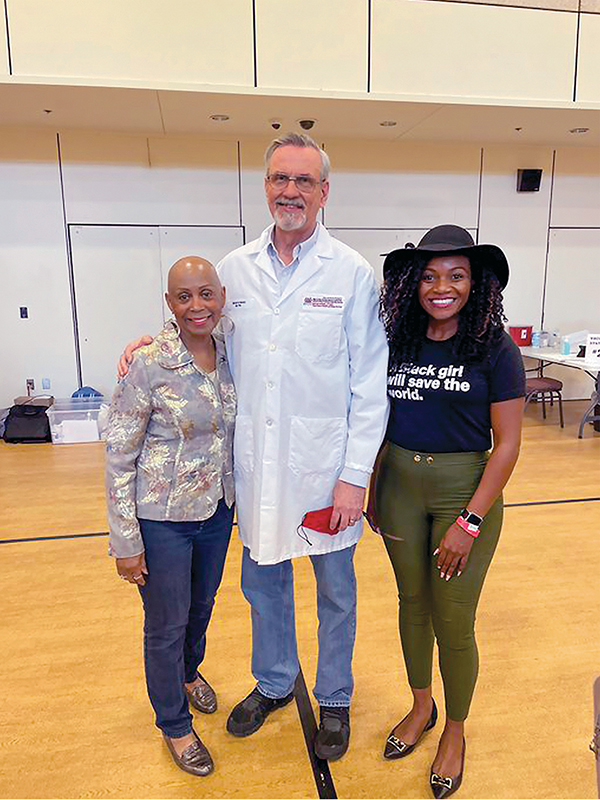

“Their names will be in the history books,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in reference to Graham and his protégé and colleague, Dr. Kizzmekia S. Corbett, on the occasion of their nomination for Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals. “All the vaccines that are doing really well are totally dependent on their work.”

Said National Institutes of Health director Dr. Francis Collins, “Kizzmekia and Barney have made contributions to human health that few others could claim.”

When Graham, m’79, returned to Lawrence in May to receive the degree of honorary Doctor of Science “for his notable contributions to the fields of immunology, virology and vaccinology, and for discoveries that have improved and saved lives,” Chancellor Doug Girod, himself a surgeon, reminded graduates—first in video remarks, when severe weather canceled the scheduled May 16 ceremony, then in person when the event resumed a week later—that “it is not an exaggeration to say Dr. Graham’s research is literally the reason we are able to gather in person here today. In my mind, that makes him a real-life superhero.”

All of which is, in the pandemic’s convoluted progression of time and events, something approaching … well … old news. At least it is for Graham, who logged four decades of research that made the vaccine’s dizzyingly fast development possible. Ever since Lawrence Wright’s book-length New Yorker article, “The Plague Year,” appeared in early January—“He is the chief architect of the first COVID vaccines authorized for emergency use,” Wright wrote of Graham—the mild-mannered researcher, a polite and gentle man of few words, has found himself called upon to share a story of which he is both proud and weary.

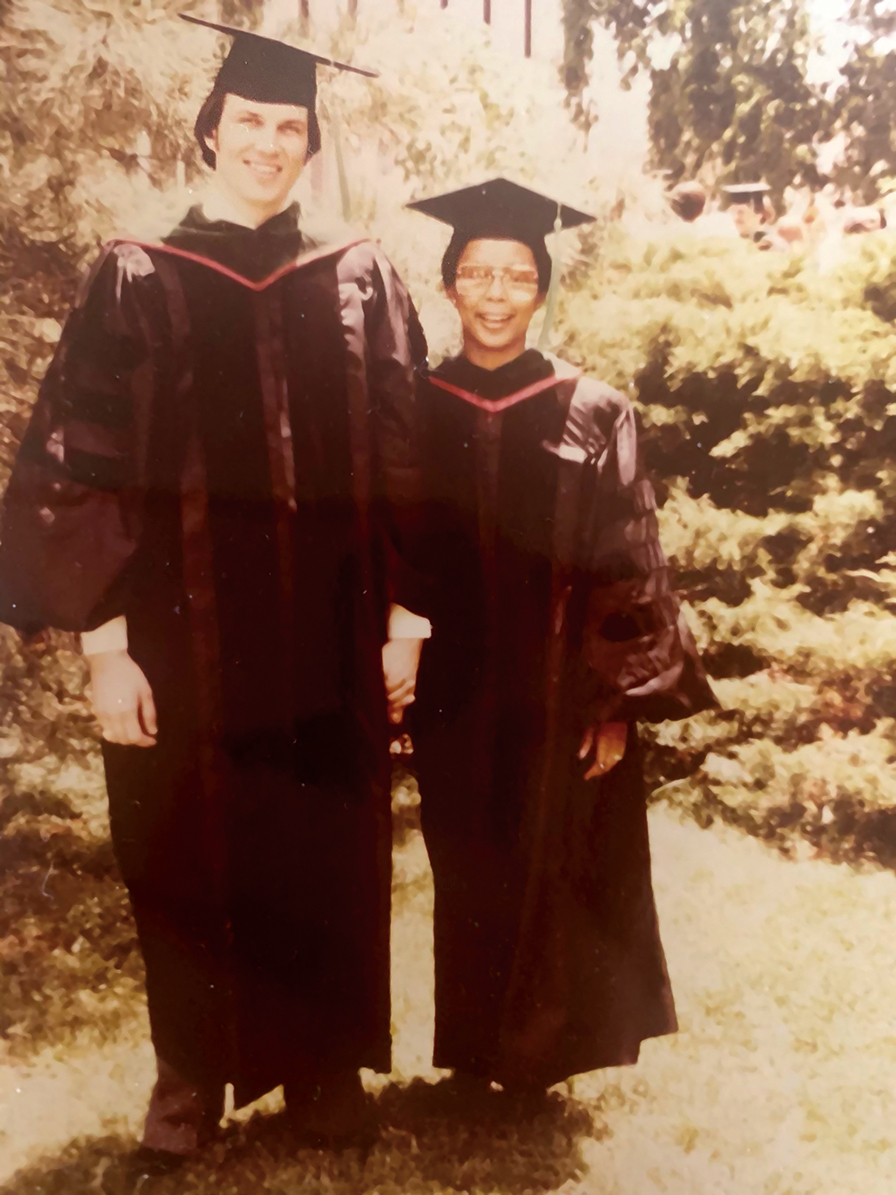

The story Graham wants to tell is, to his heart and soul, the more important of the two, and it starts with the second destination to which he was delivered by that flashy Mustang—39th and Rainbow, the Kansas City campus of KU’s School of Medicine, where Barney Graham met classmate Cynthia Turner—and then a few hours southwest, where the nascent couple chose to continue the clinical phases of their educations at the KU School of Medicine-Wichita.

“They’re just very, very special people,” recalls Douglas Voth, then professor and chair of internal medicine at the Wichita campus and now Regents professor emeritus, professor of medicine emeritus and dean emeritus of Oklahoma University Health System’s College of Medicine. “It’s easy to underestimate how significant their lives have been.”

Among the long list of seemingly minor details of daily life that Barney and Cynthia quickly discovered they shared—their fathers were dentists, their mothers had postgraduate degrees, they both changed high schools for their senior years, and their families even owned the same sets of towels and silverware—there was one interlocking aspect of their personalities that could not be ignored.

They both drove Mustangs.

“I had the better Mustang,” boasts Barney.

“Well, I had the cooler Mustang,” answers Cynthia. “Mine was red.”

Barney Graham grew up in Olathe and was an early teen when his family purchased a Paola farm, where he and his younger brother, Christopher, now an accountant in Overland Park, worked for $1 an hour, splitting their days between grueling labor and the fix-it chores required of a working farm. The problem-solving inventiveness necessary for keeping tractors and other machinery in working order appealed to Graham, as did the pride and purpose of logging long, hard workdays.

Barney graduated from high schoolas valedictorian and, judging by a fond feature story published in January in the Miami County Republic, one of the popular and respected members of his class, despite the awkwardness of joining a rural enclave where his new classmates had presumably spent most of their school years together.

Cynthia Turner was born in Nashville, her family’s home for generations, but when her father graduated from dental school, he looked elsewhere for work, far from the segregated South. Cynthia was 2 when he accepted an offer to join a Wichita practice whose previous Black dentist had recently retired. Althoughher father’s practice was at first limited to seeing African American patients, it was soon integrated and he enjoyed a successful career in Wichita.

Racial unrest roiling the country found Wichita in the late 1960s, and Cynthia’s parents decided she should return to family in Nashville, where she lived with an aunt and completed her senior year at Pearl High School.

“I was young and I was going to be in the revolution,” Turner-Graham recalls, “but I also knew my long-term plans to be a physician could be permanently derailed. My parents and I agreed that in Nashville, I could better focus on my life goals.”

When Barney and Cynthia took the first steps toward becoming a couple, they faced more than the typical hurdles of forging a relationship while still in medical school. He was white, she was Black, and in the late 1970s interracial marriage remained rare. Yet even before facing barriers thrust before them by the wider world, they first had to find out whether their own personal outlooks, biases and world views could be overcome.

“The fact that we are sitting here and still married means that we have had to talk about things that most couples don’t have to, just in order to understand one another,” Turner-Graham says. Noting that her family relied on the “Green Book” to direct them to Black-friendly restaurants and hotels when driving between Wichita and Nashville, she continues, “Understand feelings that didn’t make sense, perspectives that were foreign to the other. We would have some go-rounds. But in that process, I think, it gave us a kind of sensitivity to the world’s management of difference.”

“It’s definitely helped me as a person,” Graham says of an expanded appreciation for racial issues with which he’d had little, if any, previous experience. “I think it’s also helped me as a scientist.”

At first even their families objected. Not, Barney and Cynthia insist, because of racial animus, but because both sets of parents were convinced hardships awaited the couple and their children—hardships that would disappear if only they chose different partners.

“It was 1978. They were both having problems with this,” Graham says. “They both actually liked each other …”

“… and they agreed that we shouldn’t do this,” Turner-Graham says.

“Because,” Graham continues, “they thought that we would damage our lives, it would make it difficult for our children, and neither one of us would get to do, professionally, what we had hoped. They were just worried about our future as an interracial couple at that time.”

So, while tending to their clinical studies in Wichita, Barney and Cynthia logged more miles in their Mustangs to make frequent visits with her parents in Wichita and his in Lawrence, where his family had since moved, and to Pratt, to visit Barney’s maternal grandmother.

Florence Harkrader Hastings, c’1919, was lured back to Kansas from California—where she briefly chased her dream of designing glamorous movie costumes—by Barney’s grandfather, Fred Hastings, who lost his first wife, Myrtle, in our previous great pandemic, the 1918 Spanish Flu.

“If she hadn’t died,” notes Graham, “my granddaddy wouldn’t have married my grandmother.”

Turner-Graham recalls that on their first visit to Pratt, Florence, a KU Gamma Phi who wore a flapper dress to her wedding, pulled stacks of photo albums from a bureau to share her family’s story—soon to be Cynthia’s family, as well, Florence noted—while Barney impatiently paced the house crunching on apples.

“I think she was probably the one in the family who was most ready and willing to embrace the marriage we were starting,” Graham says. “She was quite a woman.”

“It went beyond support,” adds Turner-Graham. “That is a kind of generosity; you just had to be there to believe it.”

Despite the matriarch’s endorsement, their parents still required convincing. They requested marriage counseling with family pastors, and the young couple complied.

“Once they saw our resolve,” says Turner-Graham, m’79, “they decided, ‘Well, we might as well get on boardand try to support these crazy young people.’ It surely wasn’t their vision or hope for us, but they gave in.”

Janice Olker, the youngest of the three Graham siblings and now office manager for the Paul E. Wilson Project for Innocence & Post Conviction Remedies at the KU School of Law, recalls that while the parents “might have been concerned that the children would face struggles,” she was eager to welcome Cynthia into the family: “My perspective was, ‘Oh, that’s cool. They’re in love and there’s going to be a wedding!’”

As they entered their final year of clinical rotations and began planning their lives together, Barney and Cynthia also faced their next step toward becoming practicing physicians: residencies. They each found promising opportunities, but the rigid placement system failed to turn up a match that would accept them both. Added to the chaos of their urgent personal and professional circumstances, Barney in October 1978 pointed his Mustang east.

Among the researchers Barney met during a clinical rotation in infectious diseases at the National Institues of Health was Dr. Fauci, soon to gain fame for his work on HIV/AIDS and later the ubiquitous face of—and Graham’s colleague in—the U.S. government’s COVID-19 response. Barney then ventured to the University of North Carolina, for a rheumatology rotation; shortly before beginning his long drive home, Cynthia suggested during a telephone conversation that he visit Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, where she was certain she could secure a residency outside the match program at Meharry Medical College, a historically Black institution where her father, brother and sister attended dental school and her mother studied nursing.

So on Dec. 24, 1978, Barney Graham arrived, unannounced, at Vanderbilt University’s School of Medicine. He found that the department secretary was in her office, as were the chief resident, the head of the residency program and the chair of internal medicine.

On Christmas Eve.

The secretary allowed Graham to fill out an application, then ushered him through interviews with the three doctors.

Flush with excitement, Graham paused as he exited the final meeting, with Tom Brittingham, Vanderbilt’s free-thinking and legendary head of residency, and said, “Listen, Dr. Brittingham, I need to tell you something. My fiancée is Black, and I know I’m in the South; if that makes a difference, I just won’t be able to come.” Brittingham beckoned Graham to return to the chair in front of his desk. “And so we proceeded to have another very long conversation. He said his philosophy was, the world wouldn’t be OK until everyone was brown. The older I get, the more I think I’m going to agree with him in the end. Until we’re all a little bit brown we’re all going to have problems with each other.”

Back in Wichita, where both sets of parents were by then trying to outdo each other with their plans for the rehearsal dinner and reception, Barney Graham and Cynthia Turner were married on March 3, 1979, in a chapel on the Wichita State University campus, followed by a honeymoon in the Wichita Royale.

“And then we went back to school,” Barney says. “We graduated two months later.”

The young married couple found that life was good in Nashville. Barney rose to chief resident at Nashville General Hospital and Turner-Graham left her pediatric residency after two years when she learned that she would have to complete her final year at a Baltimore hospital. Instead, she repaid a public health service obligation incurred during medical school by joining an underserved, long-term care hospital on the outskirts of town, on the sprawling grounds of a former county mental hospital, where the growing family lived rent-free—the house was included in her benefits—with acres of lawn for their three children to play.

After three years there, Turner-Graham finally turned to her true professional passion, psychiatry, for which she entered Vanderbilt’s residency program.

“During my psychiatry residency,” she recalls, “Barney could see the excitement I had about the things I was learning. But my parents didn’t think much of psychiatrists. They said, ‘We were hoping you were going to be a real doctor.’”

She went on to become a community activist and volunteer, chairing the Metro Board of Health for several years. In 1993, a Nashville columnist included Barney and Cynthia on a list of the city’s “most interesting power couples,” noting that it was high time that women be recognized for their own professional accomplishments rather than being dismissed as their husbands’ behind-the-scenes support.

Graham’s professional life took a dramatic turn in 1982, when he saw one of Tennessee’s first AIDS patients. The tragic disease baffled physicians, and Graham immediately began recognizing disparities that haunted him throughout his career, up to and including COVID-19.

“HIV was always worse in Black and brown people,” Graham says. “It was always worse for the African continent and it was always worse for poor people, which means it was always worse in Black and brown people. So that has always been compelling for me, in that sense.”

Barney in 1985 sought out a Vanderbilt HIV lab for the required research phase of his infectious diseases fellowship. Dr. Peter Wright instead asked Graham to study respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, a respiratory virus with sometimes fatal consequences for children. By 1986, Graham had accepted a faculty position at Vanderbilt while continuing his RSV research for a doctoral degree in microbiology and immunology and assisting with clinical trials for potential AIDS vaccines.

“Barney represented to me the ultimate synthesis of a visionary, brilliant scientist, who is also exceptionally kind, generous and collaborative,” Dr. Mark Denison, c’77, m’80, director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, told Vanderbilt magazine. “I don’t remember him ever putting down the science of anybody.”

As a talented team of researchers and physicians assembled at Vanderbilt, studying an array of challenging and dangerous diseases, it was Graham, according to Vanderbilt magazine, who served as “the bridge among the various disciplines of adult and childhood diseases, as well as the basic science and clinical research.”

The Grahams in 2001 moved to Maryland. Graham had been hired the previous August as chief of the National Institutes of Health’s Viral Pathogenesis Laboratory and Clinical Trials Core. (He was promoted in 2013 to deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center [VRC] at NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.) Turner-Graham established an adult psychiatry practice in Rockville, where they lived, before also becoming medical director at a clinic in downtown Washington, D.C.

Graham’s ongoing work on an RSV vaccine—fueled in part by a nephew’s 1990 diagnosis with the frightening disease—helped create blueprints, both intellectual and, at the protein level, structural, for his lab’s COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough. As at Vanderbilt, Graham built a team that was, and remains, dynamic and fearless.

“We’ve been in a hurry at the VRC from the very beginning,” he says. “At the time we started there were 14,000 new infections in the world every day from HIV. It felt like a disaster. We all went there with the pledge that we would not let paper sit on our desks overnight, we would not waste any time. So we’ve always gone as fast as we could on everything. Not skipping steps, but just not wasting time.”

He recruited a multicultural, multiracial team that is, in Turner-Graham’s estimation, “like the United Nations. There are people from every continent except Antarctica.” Graham proudly explains that his “expanded world view,” directly attributable to his wife’s profound influence, teaches him to be “willing to listen to, and notice and pay attention to, people from other cultures.” That self-awareness, he explains, also makes for good science: “It enriches our laboratory environment. People just have different ways of thinking. There have been some very unique minds that have come through my lab, with very interesting ways of seeing the world or solving problems or reacting to things.”

Graham’s lab could be on the brink of even greater vaccine research: Fauci in July announced his hope that billions of dollars be allocated for developing pandemic vaccines in advance of future outbreaks—an idea cited as “… the brainchild of Dr. Barney Graham,” according to The New York Times. Fauci said Graham first pitched the concept in 2017, to directors at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and followed up with a paper published in 2018.

“It would require pretty large sums of money,” Fauci told The Times, “But after what we’ve been through, it’s not out of the question.”

Of course, the pandemic was not the world’s only existential challenge of 2020. There was, and remains, a long overdue racial reckoning. While his wife grieved deeply—and grieves still, aching about the world awaiting her grandchildren—Graham had to pull himself away from the overwhelming daily news reports and trust that his ongoing work on COVID-19, RSV and a fast-approaching universal flu vaccine were appropriate contributions to a better world.

He found solace in his Saturday-morning Bible study group, where he listened and learned from Black men who talked through the social crises in the context of their Christian beliefs, and of course in deep conversation with his wife, but he could not give himself over fully to the angst and fury.

“My main job last year, and even encouraged by the men [in his church group], and by my wife, was to focus on the biology. That is probably what I’m best at, and so that’s what I did,” Graham says. “There’s a lot of things that have to be staged and done in the right order so that you don’t waste time. So there was a lot to think through and figure out. I noticed all of the things happening, it was breaking my heart, and we talked about it a lot, at home and in the men’s group and with the children, but my focus was pretty much on the biology.”

Janice Olker says she still thinks of Barney as “a big kid at heart.” Her favorite picture of him was taken in her backyard, while he blew bubbles with her children. She happily admits that she noted the date for Nobel Prize announcements in her calendar—“The world is going to recover from this pandemic because of his work,” she says—but even if the Nobel proves elusive, Graham has already received one of his field’s highest honors, the Albert B. Sabin Gold Medal, for “extraordinary contributions to vaccinology.”

Olker says her brother exemplifies their mother’s favorite saying, from the Gospel of Luke: To whom much is given, much is expected. “And that was normal for us,” she explains. “We grew up in a family that helped when we could. My dad bought a house for somebody who used to clean his office. My mom was a teacher and worked at the state hospital, and one summer somebody came home to live with us and work on the farm. We just did stuff like that, and we all always have.”

She recalls asking her brother what he thought about the distrustful, even angry, reception much of the country gave to his lifesaving vaccine.

“He says, ‘You know, I’ve worked my whole life …’— in his quiet way, sometimes so quiet it’s even hard to hear—‘… I have worked my whole life to try to help people, and I don’t understand why anybody would think I would hurt them. Why would I hurt anybody?’”

Recalls School of Medicine-Wichita Dean Garold Minns, m’76, then a resident in the fledgling Wichita program when Barney and Cynthia arrived in January 1978, “He was always thought to be a very compassionate and kind individual who bent over backwards to help anybody who needed help, whether it was a patient or a colleague or anybody in the hospital. Everybody felt he was a real gem of a guy.”

Dr. Robert Simari, m’86, executive vice chancellor of KU Medical Center and Franklin E. Murphy Professor in Cardiology, recalls that he first met Graham when he was named a Distinguished Medical Alumnus in 2017, the year after the same honor went to Vanderbilt’s Mark Denison—whose lab in early May confirmed that blood serum taken from the first trial patients showed the vaccine’s efficacy exceeded not only their expectations, but even their hopes and dreams. When the Grahams returned for this year’s Commencement on the Lawrence campus, they first participated in the Medical Center’s “electronic hooding,” conducted over video, before joining Doug and Susan Girod and Dr. Akinlolu Ojo, dean of medicine, and his wife, Tammy, for the first dinner party thrown by Rob and Kelly Stavros Simari, b’82, in 16 months.

That night happened to be the debut of a CNN special, “Race for the Vaccine,” hosted by Dr. Sanjay Gupta, so the group gathered after dinner to watch along with the Grahams.

“When Barney came on the screen,” Simari recalls, “Cynthia reached over and they held hands. It was sweet. They’re an absolutely amazing couple and an amazing story.”

Simari notes that until the pandemic, coronavirus research struggled for funding and attention; even after the 2002 SARS outbreak and 2012’s frighteningly deadly MERS scare, breakthrough research by Graham and colleague Dr. Jason McLellan, then a Vanderbilt postdoc who is now at the University of Texas and a primary collaborator on the COVID-19 vaccine, struggled to find an audience. Graham and McLellan in 2017 had to submit their research to six scientific journals before finding one that would publish it. Even Graham’s now-embraced concept of vaccine development ahead of the storm languished as previous viral outbreaks waned before the efficacy of his new generation of vaccines could be developed and proven.

“He’s classic grit,” Simari says of Graham. “He did not waver from his goals, in spite of perhaps lack of funding or lack of interest or lack of attention, and the world is very lucky that he did not waver. The medical profession has always been very full of purpose. People with purpose. We value what they do, caring for individuals or parts of society, on a daily basis, but never before have we seen the potential of the impact of our profession in biomedicine on the planet.

“Barney says that 10 people live for every thousand vaccines. Two and a half billion vaccines given. That’s just … daunting.”

During the pandemic year, Turner-Graham managed an outpatient psychiatric practice while continuing her civic activities, adapting them all to a virtual environment. She is immediate past president of the Suburban Maryland Psychiatric Society and a board member of the Washington Psychiatric Society. Turner-Graham recently accepted an appointment to the board of directors of Genius Brands, which creates and licenses multimedia entertainment for children, and in 2022 she assumes the presidency of Black Psychiatrists of America. But she also intends to slow down, alongside her husband, who in August retired from the federal government.

They are leaving Washington for Atlanta, where they will be close to their eight grandchildren, eager for personal time denied them while they quite literally saved the world.

“The one thing that we are still confident in,” Graham says, “is that no matter how difficult it is between us, or how difficult life is in the world, if we get to spend time together, without too many distractions, we will be happy. And we will have fun.”

“We’ll take a walk, a bicycle ride, we might cook together,” Turner-Graham continues, almost dreamily. “It’s kind of funny. We’ve been so busy for so long that when we do get time—even three or four hours—to be together, without distractions, it’s like, ‘Wow, I’d forgotten how fun this was.’ It’s a surprise every time.”

When discussing retirement, Graham is precise in his choice of words: He is retiring from the government, not from work, or life, so he can still be expected to find projects dear to both their hearts. Health inequities, both here and abroad, are sure to get some attention, as will their church and community.

They won’t have that silver Mustang fastback to tool around in—“He drove that thing until it turned to dust,” his sister says, and Cynthia recalls that he eventually sold it for $5—but, hey, it is Atlanta, so who knows what surprise might await.

“He says ‘retire from government,’ but I know he’ll always be busy,” Olker says. “It’ll be more like Jimmy Carter, you know what I mean? He’ll probably build houses for Habitat. He’s a wonderful woodworker.”