An orthopedic surgeon’s combat lessons

KU alumnus and hand surgeon Matthew Drake shares his war experience with Ukrainian colleagues.

With two tours of duty as a combat surgeon in Iraq and years spent treating traumatic war wounds at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Dr. Matthew Drake was confident in his preparations for a late-March webinar with hand surgeons in Ukraine. Drake quickly discovered that, while his skills and experience would indeed be invaluable, he, like his Ukrainian colleagues, had much to learn.

“The guy who was hosting the webinar was in Kyiv, and right when it started he said, ‘We’re being rocketed right now.’ He could hear the bombs going off,” Drake recalls. “It’s overwhelming. You’re dealing with injured people, innocent people, people with injuries that you’re not totally sure what to do with, and you’re worried about your own family. That’s the layer that we didn’t experience here.

“I can’t even imagine what they’re going through, because at least when I was dealing with this, whether it was overseas or back here stateside, I was never wondering if my family was OK. I really, really feel for them.”

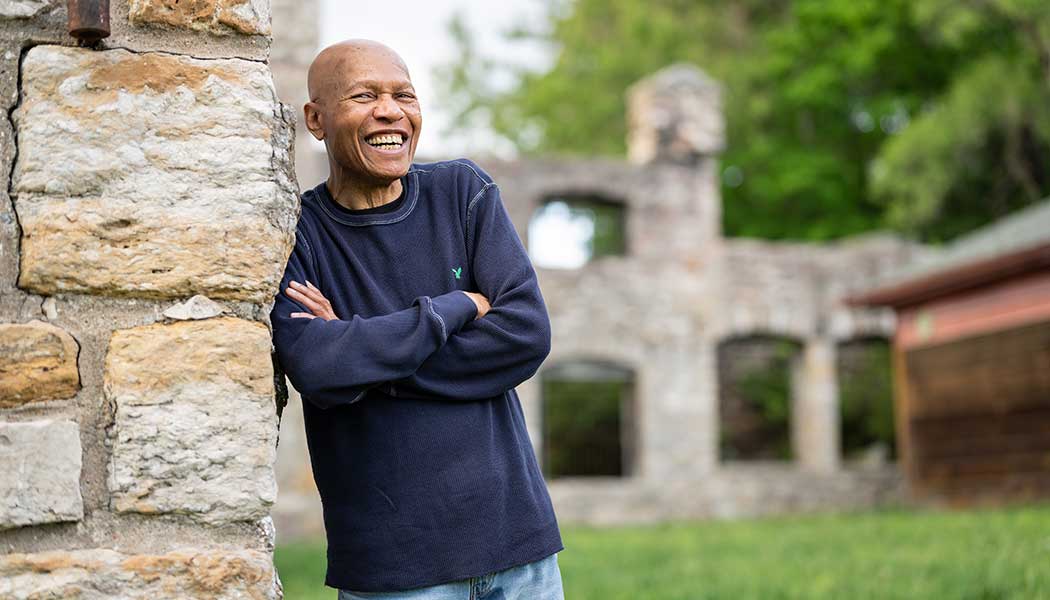

Drake, c’00, associate professor of orthopedic surgery, was one of a small group of U.S. hand surgeons with battlefield experience who in late March joined an online conference organized by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, at the request of the president of the Ukrainian hand-surgery society. Suddenly faced with traumatic, high-energy wounds to soldiers and civilians alike, Ukrainian surgeons realized weeks into the Russian invasion that they needed help.

“It’s not a matter of competence,” Drake says. “It’s a matter of experience.”

The KU surgeon explains that modern warfare’s traumatic injuries are on a different scale than those typically experienced in any civilian hospital: Falls from heights, traffic accidents and even handgun wounds are nothing like what surgeons find among those struck down by rockets, explosives and high-powered rifles, and the nature of those wounds, Drake says, requires specific techniques that are not taught in textbooks.

For instance, surgeons must learn patience: Before applying a skin graft, allow the wounded flesh time to prove it’s stable enough to heal.

“That tissue that is injured maybe looks alive right now but maybe doesn’t stay that way over the course of a couple of weeks,” Drake says. “These are the lessons that we learned. And it seems like we’ve had to go through this multiple times in our own country. When we started dealing with Middle East stuff in the early 2000s, there was really no institutional memory of war wounds, so we were going back and reading some of the literature from the Vietnam era.”

Drake grew up in Leavenworth and attended KU on an Army ROTC scholarship, which saw him through his undergraduate degree and medical school at Johns Hopkins University. He completed his internship and residency at Tipler Army Medical Center in Honolulu, after which he was assigned to a hand surgery fellowship at Walter Reed, a specialty that emerged through a combination of inspirational mentors and Army needs.

“What was unique about that fellowship was the time,” Drake says. “We were really engaged in Afghanistan then, and we were getting a lot of war injuries. When our folks would get injured overseas, they kind of get patched up and then shipped home, where we do a lot of the definitive care. Walter Reed was one of the hospitals where that was happening, so I had the fortunate experience to have that during my training, to gain some experience on the difficult war injuries for which there aren’t any good answers and really no books to read up on it. We were all learning together on what works and what doesn’t work for some of these horrible injuries.”

Six months after completing his training, Drake was deployed to Baghdad—“Definitely a unique experience to be thrown into so early in your career,” he says—where he was the only orthopedic surgeon in a combat support hospital that also included two general surgeons and a vascular surgeon.

He returned in 2016 to join a forward surgical team supporting 700 Marines who were assisting Iraqi forces fighting ISIS. His time overseas taught Drake to understand that young, fit soldiers suddenly faced with the loss of an arm or leg “feel like the person that they were is dead.”

He learned to match the healing soldiers with others who have endured similar injuries, and Drake says he’s carried those lessons to his civilian career, including at KU Medical Center, which he joined in February.

Just as soldiers had difficulty verbalizing their fears after traumatic injury, so do patients struggling with far less severe ailments as tendinitis in an elbow or hand that they fear will forever limit their movement.

“I will say something like, ‘You probably are concerned that your elbow is never going to work again, but it is going to work again and you’re going to be totally fine.’ And that person will let out a sigh of relief and say, ‘Wow, I was really worried about that.’”

As heartbreaking events have recently illustrated, grievous wounds from high-powered weapons are no longer limited to combat zones. That’s why Drake now talks through procedures with his KU Medical Center residents while treating traumatic injuries such as motorcycle accidents with exposed fractures, which require extensive cleaning and quick action to determine how much can be repaired and what is beyond saving.

“In trauma cases with our residents, I make sure they know what’s going on in my head. I talk out loud the whole time to tell them what I’m thinking, what I’m seeing, why I’m doing this.”

Drake notes that the training he helped supply to Ukrainian surgeons yet again proves the unfortunate truism that war makes for better surgeons. His own specialty of hand surgery was created by World War II-era surgeons, and the need for expertise in battlefield surgery will not soon evaporate.

“Conflicts like this are not going away. I don’t want for Americans to have to gain this kind of experience, but I think it’s going to continue. It’s unfortunate, but I’m a better surgeon because of my involvement in war, because I’ve had to deal with harder things. I’m not proud, I’m not happy about that, but that’s the nature of war.”

And yet, Drake remains optimistic: Outside of combat trauma, he praises advances such as seatbelts, motorcycle helmets, drunk driving laws and safety devices on power tools for reducing the frequency of troubling cases facing orthopedic surgeons.

“It seems like some injuries that we used to see a lot of, we don’t see as much anymore. I think those are the stories that don’t really get written because they happen slowly, over time, and very incremental. We look up 30 years later and it’s, ‘Wow, we don’t have as many people getting ejected from vehicles in drunk-driving accidents like we used to.’ I do think things tend to get better over time.”

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

/