History lived here: Montgall Avenue in Kansas City

A neighborhood tells larger story of civil rights struggle.

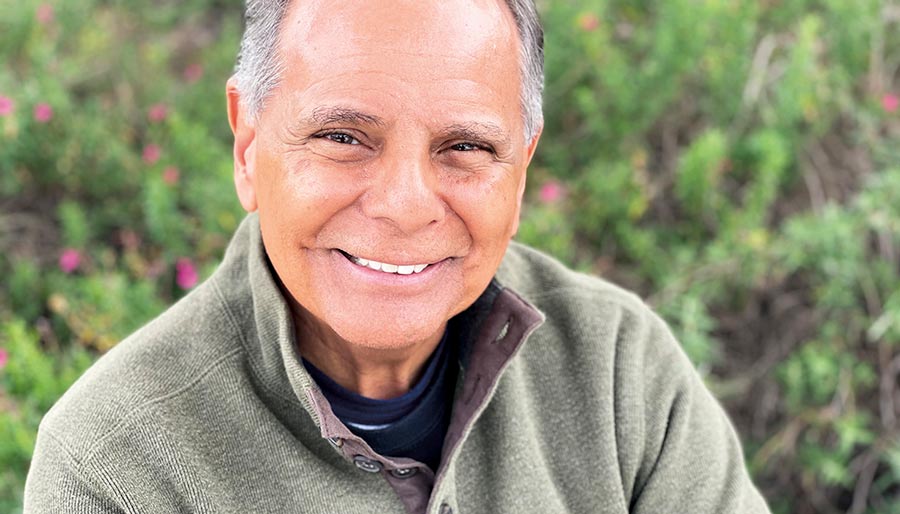

Eleven years ago, writer Margie Carr discovered Montgall Avenue in Kansas City, Missouri, by accident. Reporting a story on a historic Black church in Lawrence, she came across several letters to civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois received from the 2400 block of Montgall.

In a 1919 letter, a World War I veteran shared his experiences in the all-Black 325th Field Signal Battalion. In another, a former Atlanta University colleague of Du Bois’ whose daughter lived on Montgall invited the scholar to visit. And a 1911 letter from Anna Holland Jones told how she and other Black families on the street had been targeted in dynamite attacks that nearly destroyed a house. She asked if Du Bois and his newly formed civil rights organization, the NAACP, might help in their fight against violence.

Research into the people who penned the letters led Carr, d’84, g’89, PhD’03, to conclude that she had to write their stories: They were too rich, too layered and too historical to ignore. “It convinced me I should share not only their stories, but also the story of the evolution and devolution of Montgall Avenue itself,” she says.

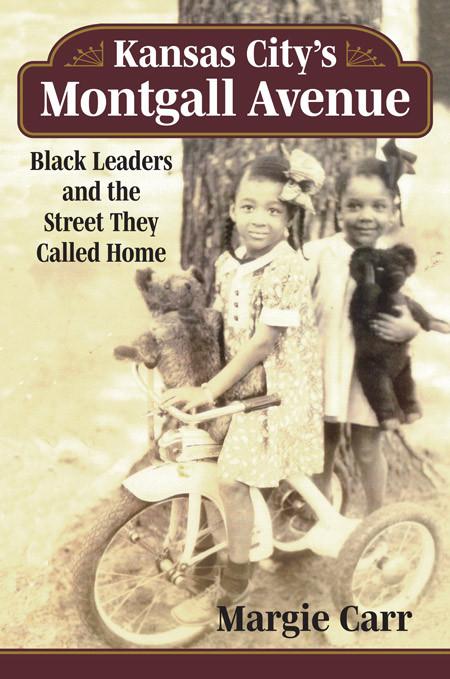

In Kansas City’s Montgall Avenue: Black Leaders and the Street They Called Home, Carr writes that Montgall’s story provides a vessel and a context for the larger story of the African American experience. “The street itself is a microcosm of the changing face of discrimination in the twentieth century as it transformed from a middle class, integrated community to the neglected, blighted place it is today.”

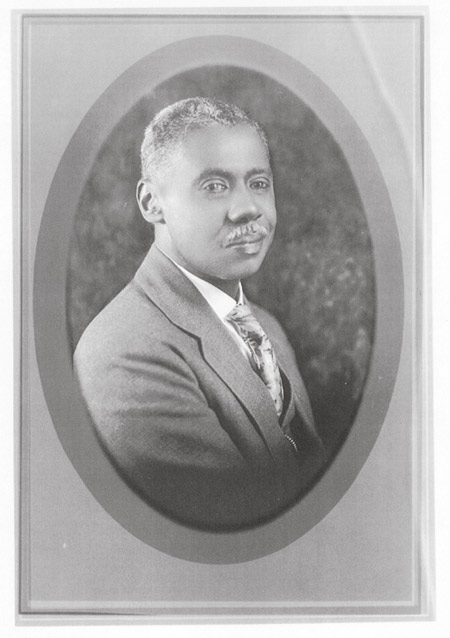

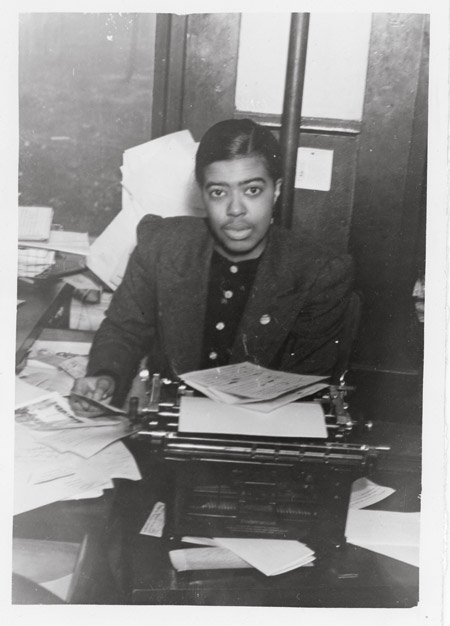

The Black residents who settled there alongside white residents founded or led some of the most important institutions in Kansas City’s Black community, including Lincoln High School, Wheatley-Provident Hospital and Roberts Motor Mart, the first car dealership in the country owned by an African American. Montgall also was home to two longtime editors of Kansas City’s The Call, one of the most influential newspapers in the country: founder Chester Franklin and his successor, Lucile Bluford, c’32.

Although not a trained historian (her degrees are in education and museum studies), Carr appreciates how difficult it is to study populations who have been marginalized historically. “Very little has been written about most of these residents,” Carr says, “and only the Franklins and Lucile Bluford have some of their personal papers in a public institution.”

So, Carr had to be creative when it came to research. “Fortunately, the earliest Black residents of Montgall were active politically and socially. They belonged to groups, and I was able to find them in the social pages of various Black-owned newspapers,” she says. “They also wrote letters to political leaders, so there is some of their correspondence in the collections of Missouri governors like Arthur Hyde and Forrest Donnell and even President Truman.”

The lives of Montgall Avenue residents were informed by attitudes within the white community that morphed into government policies such as the Depression-era federal program that redlined neighborhoods like theirs. “It can be hard for people to appreciate the impact that government actions can have on people, because the effect often isn’t immediate.” Carr says. “How can one examine how redlining affected an individual person? But it’s hard to deny the devastating consequences of the policies when you focus on a street.”

Although the 2400 block of Montgall housed many of the city’s most important Black leaders, Carr wasn’t thinking about residents’ professional accomplishments on a recent visit to the street. Rather, she focused on the more intimate connections that tie neighbors together. Pointing out the home of John Edward Perry, the physician who founded Wheatley-Provident, Carr noted that he attended the deaths of several neighbors. “John Bluford died at home,” she said, pointing to the home of Lucile Bluford’s father, “and Perry signed his death certificate. He also signed George Gamble’s death certificate,” she said, pointing out another home on the street. “I think about those things a lot. Things that happen in our homes: the celebrations and the arguments with our loved ones. Our home is where we eat and sleep. It’s where we get dressed every morning. The most intimate things people do take place in our homes.”

Kansas City’s Montgall Avenue, which last fall won Historic Kansas City’s George Ehrlich Award for an outstanding publication, illuminates a street in the heart of America by lovingly sharing the stories of the people who lived there. Carr hopes it continues to find an audience.

“I wrote this book because I care about Montgall Avenue,” she says, “and I want others to as well.”

Editor, publisher, activist

In 1939, Bluford was accepted into the University of Missouri’s graduate journalism program; when she tried to enroll, she was told the school wasn’t open to her because of the state’s separate but equal policy. With support from the NAACP, she sued the school, pursuing her case to the Missouri Supreme Court, which ruled in her favor. But Bluford never attended: The university closed the program, citing a shortage of students and faculty caused by World War II military service.

Bluford remained a civil rights leader and used the pages of The Call to speak out, especially on Jim Crow laws. She was later honored by both Mizzou and KU, which awarded her the Distinguished Service Citation in 1990.

Photos courtesy of University Press of Kansas

/