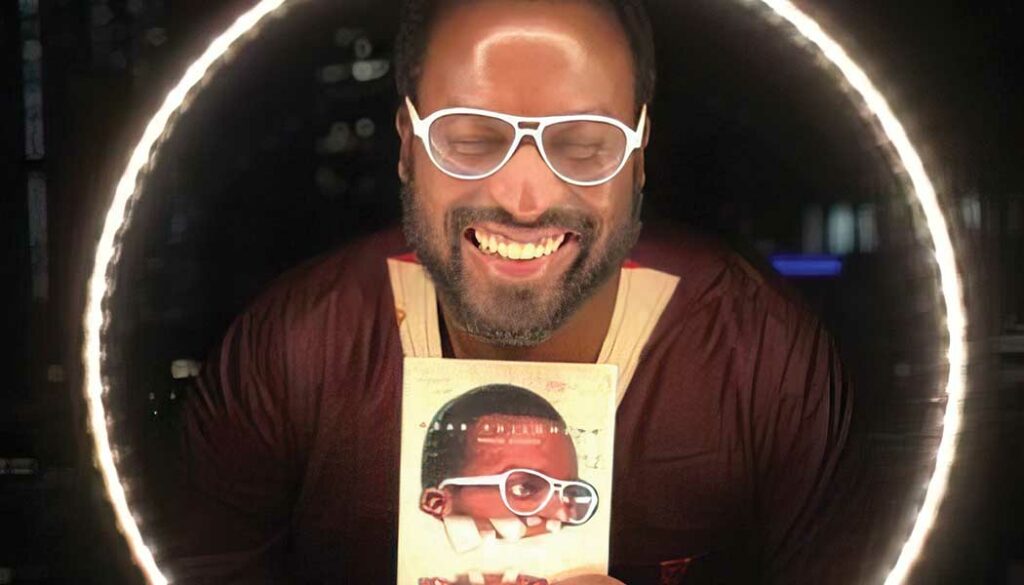

Author’s creative flame burns brightly for others

Novelist Mugabi Byenkya shares his journey of overcoming paralysis and pain.

When Ugandan author and poet Mugabi Byenkya describes his creative emergence as a “very painful form of artistry,” he’s not referencing coffeehouse angst salved with clove cigarettes and expensive leather notebooks. Rather, Byenkya speaks of the paralysis that has clenched the right side of his body since experiencing his first stroke as a 9-year-old schoolboy then living with his family in Bangladesh.

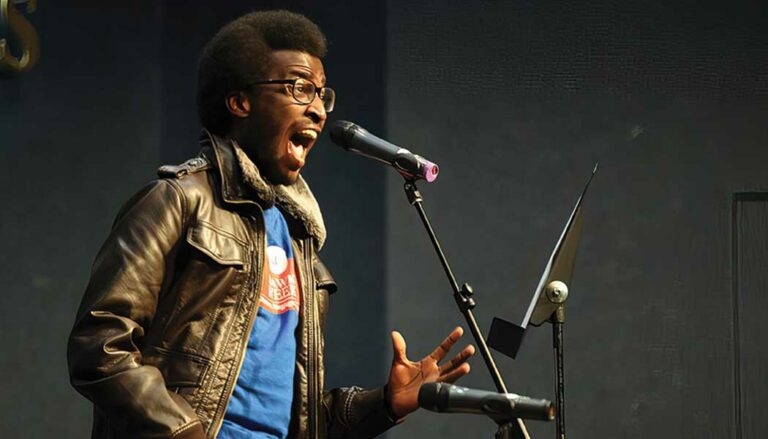

“I would write for 15 minutes, and the exertion that entailed on my body was like having an hourlong seizure afterward,” says Byenkya, c’14, c’14, who makes his home in Kampala, Uganda. “There was a lot of, ‘Is this worth it, all the pain I’m putting my body through?’ Now that I’m removed from it, I can see that it was worth it, for all the lives I’ve been able to impact.”

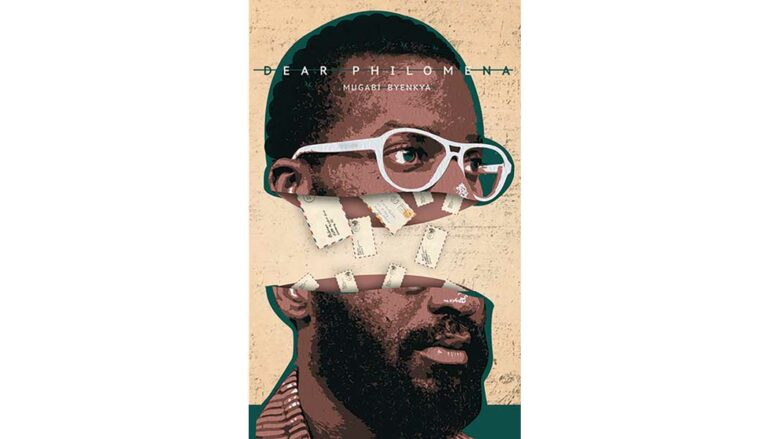

Byenkya “very deliberately” crafted Dear Philomena, his 2017 debut novel-memoir, with text-message conversations between himself and a character named Philomena, interspersed with diary entries and social media posts, to make the book accessible for readers, such as himself, who find heavy blocks of text incomprehensibly dizzying.

“I’ve had people tell me it was the first book that they’ve been able to read in years, because of their disabilities,” Byenkya says. “I’m still in awe, and uncomfortable, because of the power that words have, but it teaches me that it’s a power that should be wielded responsibly.”

Byenkya’s father worked for the United Nations Development Programme, which took the family to stations around the world, and he fondly recalls gaining awareness of the power of books during happy Sundays spent with the entire family curled up on the couch, lost in their books.

Although he experienced occasional migraines, Byenkya felt the first stirrings of the childhood stroke that changed his life at a school carnival; later that day, during an argument about whose turn was next in their board game, he grew frustrated as his brothers and friends ignored his shouts: “It’s Nadine’s turn! It’s Nadine’s turn! And then I realized, no sound was actually coming out of my mouth. The only thing coming out of my mouth was an awkward croaking sound.”

His mother, a nurse, took him to a doctor, who dismissed the episode as dehydration from playing outside all day at the carnival. The next day, his teacher commented that his beautiful handwriting was faltering, his mother asked why he kept clenching his right hand, and he even walked with a limp—none of which he was aware of.

Thanks to benefits provided by his father’s job with the U.N., Byenkya was soon being treated in Singapore, and he began a new life filled with physical therapy, intense pain, and growing feelings of anger and confusion. He was 13, living in Thailand, when his father died unexpectedly. Along with the emotional pain, the family suddenly faced financial ruin and the loss of their health and education benefits.

After five years in his parents’ native Uganda, Byenkya began sending out college scholarship applications; KU answered his call, and on Mount Oread he found welcoming communities in residence halls, where he lived and worked, and the University Honors Program. He graduated with departmental honors, earning degrees in global & international studies and environmental studies.

Although he had yearned to become an author since he learned to read, Byenkya opted for a “practical and stable” career path, and won a fellowship to the University of Michigan’s graduate program in environmental justice. Everything crashed to a halt at the end of his first year in Ann Arbor, when a pair of strokes struck within a week, leading to chronic pain and fatigue, a seizure disorder, and a “volatile” recovery process.

When doctors told him he would not live to see his 24th birthday, Byenkya heeded his heart’s longing to write.

“I wanted to be an author my whole life, but I never fully embraced that,” he says. “So I was like, I need to at least try my best to write a book before I die.”

Dear Philomena was a 2018 bestseller in Uganda, and he continued his creative burst with poetry, comic books and theatre residencies. With his second book already with his publisher, Byenkya, now 31, recently released a “concept mixtape” titled “Songs For Wo(Men) 2.”

“When somebody calls me an inspiration, it honestly makes me uncomfortable, because I feel like I haven’t done enough to be an inspiration,” Byenkya says. “The most important thing I’ve learned is that you can’t overcome everything in life, but you can figure out ways to manage. And I’ve managed pretty well, so I’m proud of myself.”

Chris Lazzarino is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

/