The Last Cattle Drive Redux

When The Last Cattle Drive appeared in 1977, the comic tale of a prickly Kansas rancher’s quixotic bid to drive a herd of cattle from Hays to Kansas City became an unlikely best seller and Book-of-the-Month-Club selection. After a brief, distracting dalliance with Hollywood—a rumored film starring Jack Nicholson was never made, and a lawsuit prompted by its demise hastened the bankruptcy of MGM Studios—Bob Day, c’64, g’66, got back to writing novellas, novels and short stories. (A 550-page opus of his short fiction, The Collected Stories, will be published in December by Serving House Books.) But never did he pen a sequel of The Last Cattle Drive. Until now.

For Not Finding You, excerpted here, finds Leo Murdock in Paris. Removed by age and distance from his days as a young ranch hand, in search of lost time and a lost love, he looks back on his Kansas adventures from afar, his recollections as immediate as his daily round in the French cities and villages he frequents throughout the novel. That’s a tribute to Day’s keen eye for detail and fine feel for the rhythm and rhyme of ranch life. “In all my fiction,” he has written, “I’m mindful of Hemingway’s remark that he knew the time and place on every page.” That time and place, in Day’s book, is distinctly, indelibly Kansas.

—The editors

I have come to Paris in search of lost love. Many have done it.

I live in a small apartment on Rue de Poitiers just behind the Musée d’Orsay that I share with a character from a short story I recently wrote. In spite of who we are to one another, there is room enough for both of us. Monique’s collection of Montaigne’s selected essays (in both French and English, with her admonishment inscribed on the flyleaf—traduit par Montaigne tout seul) is on the desk where I am now typing—along with her French/English Larousse Dictionary, inscribed: For the first time you see Paris. With me! I have bought my own Plan de Paris.

It is fall here. The Bateau Bus is still on the Seine, dropping passengers at various stops: Eiffel Tower, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Notre Dame, Hôtel de Ville, among others. I am up high enough to watch its wake. I can see the Pont des Arts. I have Monique’s postcard.

By now I have lived here a year. (My fictional doppelgänger has been here a month or so. In this way he has moved in on me.) I do not know what has kept me from what I am now writing, nor did I know I was being kept from it. For Not Finding You is my provisional title; I hope that will change. I walk a lot to make that possible. Like my character, I am keeping a diary.

I once worked on a small ranch north of Hays, Kansas, in Buckeye Township—above the Saline River and the breaks that run into it. Some days I taught school as a substitute. I lived in that country six years before I left for Paris. I did not marry.

One Friday, toward the end of summer, the rancher got a call from the banker who had loaned him money to buy the heifers. We had hopes of breeding them and selling the calves for a fat profit. But the price of money was going higher, and the price of beef was going lower. That’s when the phone rang. I told the banker that the owner was outside but I would get him.

I will use Buck for his name, but that was not his name. I am superstitious about some things, and writing about the dead and using their names is one of them.

“Hello,” Buck said when he got on the phone. He had been walking toward the Home-House when I called him. Long, even strides. He was a tall man with big hands. The phone vanished in his fist. He listened and frowned.

“I don’t have that kind of money unless I sell the herd, which I won’t,” he said. “They’re just bred. And the price is piss-poor.”

He was shaking his head back and forth. That usually meant he was about to swear. He was gifted at it, and the more he shook his head before he got started, the richer the gift—and the better it gave.

“Tell those pig buggers on your board that’s what they get for lending money at 14 percent.” Hanging up, he said: “You guys are lower than snake shit at the bottom of a posthole.”

It wasn’t funny, but later that night when we poured ourselves Black Jack it got us laughing as we retold the story more than once, back and forth, adding something with each version. Not about bankers being lower than snake shit at the bottom of a posthole; that was for real.

There were just the two of us working the place in those days. The ranch had been in Buck’s family for three generations; however, Buck and his wife, Ellen (also not her real name), had lived most of their lives in Hays. When their hired man died they sold the Hays house and moved to the ranch. And I was to move out from my apartment in Gorham to be with them, living in a small Sears and Roebuck cabin that I was fixing up to the north of the larger Home-House. But then Ellen died in a crash with a grain truck on the Seven Hills Road from the ranch to Hays. I was still in Gorham when it happened. It took me the fall to fix up the cabin and then I moved in and began helping Buck more or less full time.

The following spring Monique started coming out. We had known each other at the university but got separated the way you do when you are young: she went on a student exchange to France; I took a job teaching school in Gorham. Before we found each other again there had been another woman in my life. Very crazy. There had been a man in Monique’s life. Not that she talked about him much. His name was Bruno. That was his real name. As Monique is hers. They met here in Paris.

Monique would drive out Fridays from Lawrence and stay through Sundays from teaching grade school. In summers she’d live with us weeks at a time. Monique was tall and trim. Hair cut just above her ears. A pail of fresh milk, as Buck called her. And blond nearly to cream. We lived together that way for about five years until she returned to Paris.

Well, we had Amos, a black lab of mine, and later, Murphy, a mutt that Monique found at a rest stop. Everywhere were chickens scratching and hens running to hide their eggs—plus rabbits and squirrels and cats mixed in for good measure.

At the beginning there was Milky, who was past her prime, but now and then I’d give her a try. I thought it might please the old cow to be of use, the ranch cats gathered under her, milling and meowing. “You get in some good thinking putting your head into the side of a cow,” Buck said when he saw me going into the barn with a bucket.

The first summer Monique stayed with me, she put her head into the side of Milky as much for what I’d told her Buck had said as for the cats.

“It works,” she said.

“Good thinking?”

“Yes,” she said.

“What do you think about?”

“Us. That you are mon coeur. ‘My dear heart,’ in English. I will teach you more French as you want to learn.”

I went to get a Polaroid Ellen had bought when they first moved to the ranch.

Later that summer, Milky died one night and it was Monique who found her in the morning. Buck hooked up the backhoe to the tractor and dug a burial pit south of the Home-House, where, after Buck hired Patsy a year or so later, she planted her first garden, never knowing why it came on so well from the beginning—and for all the years afterward. It seemed a pleasure to keep the secret.

The evening we buried Milky, Monique sang a version of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” in her fine alto voice, with the chorus as “The Night Old Milky Died,” and there was no irony in her version, only woe, even though she had not known Milky but that summer.

“She’s a fine woman,” Buck said to me the next morning when we were alone over coffee. “A pail of fresh milk to be sure, but more than that.”

Later, there was Moshe, a one-eyed tomcat that Patsy brought out to catch mice but whose specialty was not mice, but anything bigger than himself: chickens, box turtles—in addition to the pheasants, ducks, turkeys, rabbits and deer we’d hang in the well house behind my cabin. Moshe would get to the game with a leap and a hiss and hang on. I’d find him chewing as best he could on a shot mallard until he fell off and went to look for a yard rabbit. Without Milky and with the arrival of Moshe, the other cats hit the dusty trail. Buck used to say that the farms and ranches in Western Kansas were so far apart each had its own tomcat. Moshe was ours.

One blue blizzard night the first winter after we hired Patsy she brought Moshe into the house and fed him grocery-store cat food.

“You know what that is?” Buck said, pointing at Moshe.

“A cat,” said Patsy.

“That’s the only animal in the world that can turn money into cat shit.” It was Monique who gave Moshe his name.

Sometimes you’d see rattlesnakes. Two owls: Dame and Monsieur Pas Blanche as Monique named them, saying that meant “Not White” in French. Doves came in and out of the shelterbelt. The summer he got rattlesnake bit, Moshe took himself into the heat of the south pasture to die.

“Leave him be,” said Patsy when Monique thought she might drive him to the vet. “Leave him to himself. He knows what he’s doing. When he’s gone the fire ants will finish him. ‘What goes around comes around’—Jesus-God.”

We had hired Patsy to help with the chores around the Home-House, cook our meals, and make a garden—and for her company—in exchange for her wage and meals.

We were good company, and not hard to please with what she fixed: Stews and soups in winter at noon, what is called “dinner” in that country. Chicken or pig for supper in the evening. Buffalo meat from a bull Patsy’s hippie nephew and his girlfriend won in a lottery and had us kill. Channel catfish out of the pond. Ducks we shot. Pheasants. A deer in winter. Cold beet and vegetable soups from Patsy’s garden in summer. Salads as well from the garden for what Patsy called our “cesspool systems.”

Patsy was no rose. Not even a shriveled flower at the stem’s end. Mostly thorns—especially if you crossed her. And given to “Jesus-God.” That was her word: Jesus-God. Also, we didn’t live in Buckeye Township, Ellis County; we lived in West Jesus Land, Kansas. Every place else was The Rest of America.

If Patsy had a dress we never saw it. (Well, I did: once.) Summer or winter she’d wear blue-striped bib overalls and work boots. In winter she layered shirts and sweaters. In spring and early fall she’d wear T-shirts, and in summer, when it got up past “Hell’s high roast number” (100), she’d wear nothing but her bib outfit and sockless boots.

In the side straps and pockets Patsy carried pliers, gloves, a beer opener (bottle or can), baling twine, a snub-nosed .22 revolver, golf balls she’d put in the hens’ nests to fool them into setting, a small cloth bag for eggs, and, always hanging at her side, a hatchet for beheading chickens and snapping turtles on the cottonwood stump by her garden.

Buck’s ranch was small, but good grass. No plow land. Springs that flowed into the draws, deep water wells, one big pond and a few smaller ponds in the horse back pastures. We had windmills that fed the stock tanks, and there were limestone outbuildings from an abandoned homestead on the northwest quarter. Good fences, solid gates with deep-buried dead men to hold both corner posts straight. Stout corrals. Rattlesnake quarters with rock outcroppings and soapweed down to the river.

There is a man on Rue Bonaparte who is especially curious because he is not so much woebegone as a man of more than modest accomplishment in another life: a man who went out one afternoon from a wife and family in a remote French village in the Dordogne to get a bottle of wine and never returned.

Here in Paris he has used what funds he has to buy a sturdy three-wheel bike with a tow-behind small camper of sorts. He arranges himself out of the way under an arch, and unlike the other homeless he does not beg, but instead has a small bowl set out should you want to leave some change. And a bowl for the dog as well—a dog that reminds me of Murphy. I am trying to make friends with “Murphy” by bringing him table scraps. As to the man, we do not talk but nod to one another. In his leaving where he came from

to live in Paris we are camarades. And if my editor comes here she will observe that the man and I look alike. I think so myself.

I have also seen a woman now and then in a café on the Right Bank where I sometimes take a coffee. She has a battered mink coat she wears when the weather is cold and carries when it is not. I am reminded of a character out of a Jean Rhys novel: Good Morning, Midnight, I think. At first we just looked at one another; more recently we have begun to nod. I think we have resolved never to talk, but how I sense this (in myself and as well for her) I do not know. The transmigration of tristesse. And then there is this from Montaigne:

The Italians do well to use the same word for sadness, “la tristezza,” as for malignity: for it is a passion as harmful as it is cowardly and base—and always useless.

Our herd was about 200. First-calf heifers. They had been bought cheaper that way, even though we’d have trouble calving them—which we planned to do in January so we could beat the late summer market at the sale barn when everybody was bringing in their cattle before the grass dried up and winter came on. Supply and demand. But with the cattle market, it’s mostly luck.

One day we lost two heifers on the Saline when they got into quicksand. I found them up to their bellies, dead, the water going around them, making eddies. Maybe one wasn’t dead, but trying to rescue her was foolish. My horse got his front hooves stuck at the edge of the river, and I had to rear him up and spin around to firm ground. Across the river was Mencken Cody’s ranch, so when I got back I told Buck he might give Mencken a call about the quicksand should he have any cattle along the Saline. It was Mencken’s Gomer bull we were using to mark the herd.

A week later when Buck and I rode back to check our fences the heifers were mostly skin and bones. Both heads were on the carcasses. Eyes gone.

“At least someone got to eat,” Buck said. “‘What goes around comes around’ isn’t bad thinking.” We rode back to the Home-House, and when we got there Patsy was ringing the yard bell for dinner.

There were lodgepole pine fences around both the Home-House and my cabin, and the larger yard of about five acres was fenced with barbed wire. In that yard were tool sheds, calving pens, horse stalls, and a storage garage where we worked on trucks and parked equipment. To the north, west and south ran a WPA shelterbelt of shrubs and trees, leaving the east side open. One year we found a beehive in a dead cottonwood tree on the south side. We let it get started until the following year, then every year after that I’d put on a long-sleeved shirt and gloves and stretch a ski mask stocking cap over my head and dig out a few combs with a small trowel, while leaving most of it intact. From the honey Patsy made syrup and oatcakes.

We also had a pack rat named Gone. Whatever was missing: gloves, hats, light tools, a washed dish towel that blew off the clothesline, T-shirts left out overnight from a summer day, rags from the shop bench, once the ski mask I put on the porch of the cabin—it was Gone. For some unspoken reason we all agreed to leave Gone alone—with Buck only saying that what goes around doesn’t always come back around.

“He is our archaeologist,” I said.

“What’s that?” asked Buck.

“They find out who we were by sorting through our trash.”

“Sort of like they are the socialists of the dead?” he asked.

“That will be Gone when he’s gone,” I said.

One Friday in late summer Monique was to come out after a teacher’s workshop to stay a week or so until school started. Saturday was Patsy’s birthday and the plan was to fix her a meal in the Whorehouse Room. That was the big room in the Home-House with a Woodsman stove at one end and a large fireplace at the other that we’d stoke up with cottonwood on special occasions. After Patsy started cooking and cleaning for us we let her decorate it.

“She wants to buy red wallpaper,” I had said to Buck. “It’s furry with gold gilt in it. And paint the window trim red.” There were two windows on the north side of the room, on either side of the Woodsman. By this time Patsy and Monique had met and, for reasons that were mysterious to both Buck and me, become chères amies—as Monique put it.

“And hang framed mirrors,” I said.

“Just as long as she doesn’t get scared away for seeing herself,” Buck said.

“And chandeliers. When she’s done it will look like a whorehouse.”

“Good thinking.”

One weekend early in the summer when Monique came out we went to Hays with Patsy to buy what she wanted. She had us put down a purple shag carpet. She covered the chairs with deerskins, and the couch with a large bedspread that had a stag’s head in the middle. We weren’t allowed in with our work boots. I bought a player piano from the Woodcutter’s Widow in Bly who was selling out piece by piece. The deal came with 50 rolls of old-time songs—all of them in good shape. Even though Monique could play the piano (and a guitar that she’d leave so she didn’t have to bring it out each time), she’d pump the pedals and we’d all sing along: You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are gray, you’ll never know dear, how much I love you, please don’t take my sunshine away. Patsy would join in.

“She can’t carry a tune in a pickup,” Buck said. But when we went “goodbye” with a stout glass of Black Jack, we didn’t much care.

After I bought the piano, Buck and Patsy bought Monique a French horn we also kept in the Whorehouse Room.

“I don’t know how to play it,” Monique said when they gave it to her.

“Well, it’s French and on sale,” said Patsy, “and I know how you like France so…”

“I can learn. And thank you,” Monique said. “Both of you.” I suspect she knew it was Patsy’s idea and Buck’s money.

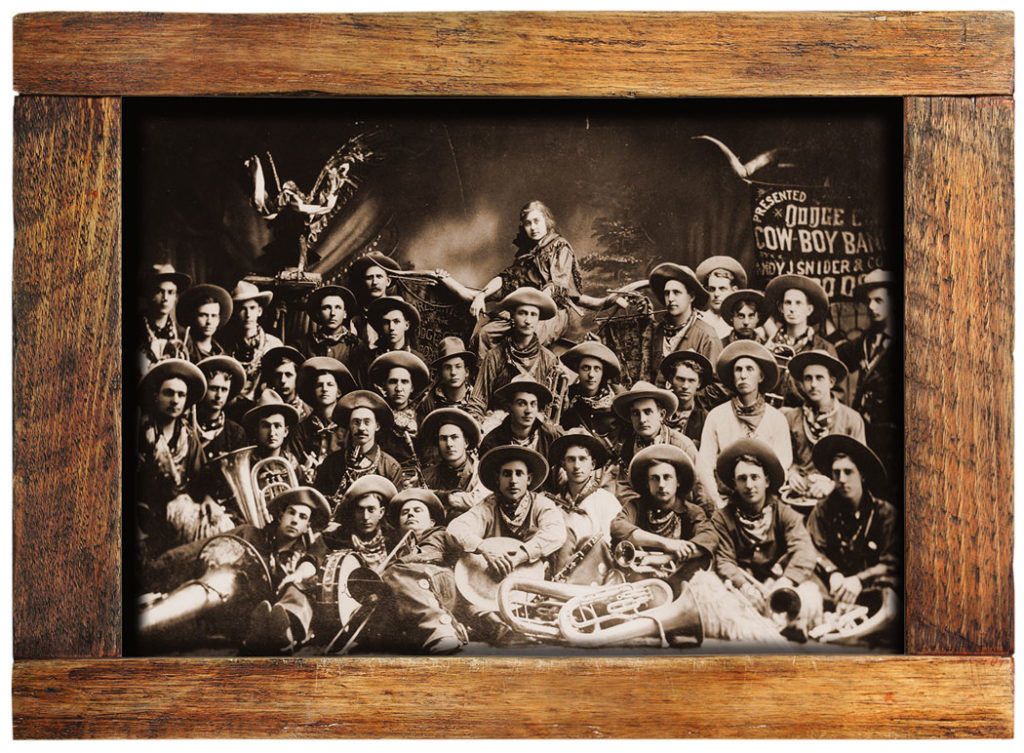

The next time out, Monique brought an enlarged photograph of the Dodge City Cowboy Band from the 1900s that she got from the Kansas Historical Society. It showed 20 or so bug-eyed and half-drunk cowboys with their instruments, some men lounging on the floor in the front, others on risers leading up to a lone woman, young to be sure, but not a pail of fresh milk, sitting on a set of very large longhorns. There were tubas and trumpets and tambourines. Drums and clarinets. One man was holding a pistol. But no French horns.

“For the Whorehouse Room,” Monique said when she gave the picture to Patsy. It was framed in barn wood.

“I like the men with the tubas,” said Patsy.

“They are upright E-flat altos,” said Buck. “Not tubas.”

“How did you know that?” Monique said.

“I used to play one in the high school band,” Buck said.

“Then you can play my French horn.”

“I only play upright E-flat altos,” Buck said.

“I’d like ‘Red River Valley,’” said Patsy, when she saw that Monique had brought a book of French horn instructions and sheet music. For my part, I had bought a music stand also from the Widow Bly.

“I’ll try,” said Monique. “I’ll try.”

Over time we’d hear Monique doing what she could with the French horn, and when she was not around, we’d find Patsy giving it a polish.

“Jesus-God told me to keep it shiny for Monique,” she said.

To Patsy’s credit the Whorehouse Room was always clean, and it looked as if a high-dollar Dodge City dove of low moral character might leave her perch on longhorns and join us at the player piano to sing “Red River Valley.” And, as it turned out, the Whorehouse Room was where we had our Black Jack every night after work—but not before we had showered, tended to cuts and bruises, combed our hair (Patsy was big on combed hair) and put on clean clothes. “‘Be clean and combed for Jesus-God once a day.’ Evaticus 7:3.”

“Goodbye,” Buck would say by way of a toast when he tipped his whiskey glass. Goodbye, so said we all as the pain of work began to fade.

Sometimes I’d cook for Patsy. She’d sit in the sunshine on the south side of the house by her garden, pulling on her long-necked Coors. She liked being called to dinner or supper instead of ringing the bell for the calling. Not always, but for a break. Small luxuries are better than big ones if you live in the country. And I liked fixing the meal. Even setting the table and washing up.

Buck didn’t cook. Only slabs of venison on the pit grill when we shot a deer. Patsy knew how to make jerky, and we had a hand-crank meat grinder for everything but the good cuts. A deer could feed us through to spring if we portioned it out: steaks, ground meat for chili, a couple of roasts, jerky for the truck when we were windshield ranching. Patsy would mix the ground deer with the ground buffalo and call it “two-beast burger,” and she’d use it for meatloaf, chili, or “two-beast burgers.” We tanned and tacked hides on the south side of my cabin to cure.

Patsy grew hot peppers that she’d string and hang in the kitchen to dry for the chili. And braid onions and hang those in the well house. Keep carrots and potatoes covered with straw so sometimes we’d have them into December. She planted sweet corn and tomatoes and green and red salad peppers. One year she had me bring sand up from the Saline and mix it in on the south edge of the garden where she grew watermelon. She also asked for the ashes from the woodstove and the fireplace and she’d mix those into the topsoil. The garden got better until it became “abundant.” It was a word Buck had once used and Patsy borrowed. “The abundance of Jesus-God,” Patsy would say when looking over the garden. Most anything good in those days was “abundant” to her. Patsy liked words. We all liked words. Propensity was a favorite. “She’s an abundance of Jesus, that’s for sure,” Buck would say after Patsy had gone off on one of her religious benders. “With a propensity for Hell,” I said.

“That too,” said Buck.

“Have you decided to tell her about Milky?” I asked.

“No. Let her have Jesus-God as the tomato deity and we’ll worship the old cow.” Patsy had me build a “moat” around her garden by putting up a chicken-wire fence so she could keep a dozen or so hens there to eat the grasshoppers before they got to her plants. The other chickens ran in the yard, but Patsy thought the best ones for cooking came from the moat because of the grasshoppers they ate. The yard chickens were for soup or stir-fries. And eggs.

“When Jesus-God made a chicken, He was thinking of women,” Patsy used to say. “You take a chicken and a woman who knows how to pick it and she can feed all of West Jesus Land, Kansas, and half of The Rest of America, and be pleased to do so.”

One spring when we had good rains the plum thickets around the edge of the ranch bloomed. I cut the flowers for Monique when she came out, and for Patsy as well.

“We’ll have sandhill plums in the fall,” Pasty said. “I can make jam of them.”

“You can also put them on the table for treats,” said Buck. Sometimes that fall when we were windshield ranching, Buck would get out and pick plums for ourselves and to take back to Patsy.

My diary seems to have grown a self unto itself; now there are three of us here in Paris, plus of course shades from the past as we go along, one of us (moi) looking over my shoulder at the other two—or maybe we are arm in arm.

In any case all of us wonder at my extensive details about the food in Kansas, given that here in Paris all along the rues and mansard roofs there are gifted cafés and restaurants.

My list of Kansas foods might be only a slim pamphlet, but Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Taste at over 400 pages is a très fat one. I like his English title: The Joys of the Table. I hereby steal it for our Kansas fare.

It is my diary (he/she needs a nom de plume) who wonders why we were all more pleased with sandhill plums and caught channel catfish than a homard thermidor. And it is also true that all the time I lived there we never went out for dinner.

We had horses to work the pastures down along the river; two old four-wheel-drive pickups with granny gears; a John Deere 4010 for ground we leased west of us to grow oats for the horses; a square baler (that was always breaking down) for the prairie hay when we could get a cutting, and for a small alfalfa patch in a creek bottom leading to the Saline. All of it mortgaged to the bank. Not the horses. Not the Home-House nor my cabin. Not Milky. They can’t take what you ride or where you live. Or what’s dead. It was good while it lasted, and to be fair to the fates, it lasted quite a while. Even with Ellen’s death partway into it. And even after we were broke. There’s a lot you can do without much money if you put your mind to it, and it’s not a bad use of your mind. In this way, we ate well and lived well, being careful. For a long time nobody got badly hurt or sick. We stayed together.

When the end came, it was Patsy who helped me bury the dogs, dead two months apart, in the shelterbelt west of my cabin, their nametags nailed to a tree near their graves. With the Polaroid I took Patsy’s picture by the tree, then we went to town where Patsy put on her dress for the service, what there was of it, just the two of us standing by the flat stone marker with no name on it. “I wonder where he went,” said Patsy.

“Maybe nowhere in particular. Maybe somewhere,” I said.

“Not to be found,” Pasty said. “He once told me that was where he wanted to go.”

After that we drove back to the ranch and Patsy packed up pots and pans, stuff, the French horn, books, and three live chickens to take to town. I helped her move. There was snow in the air. Later, Mencken Cody wrote me here in Paris to say Patsy had come back out to the ranch the following summer and they found her half-crazed in the heat and the wind of a bad August, tearing down the chicken moat around her garden and shooting pistol shots into the sky at the Anti-Christ. Mencken took her to Blaze to live with her sister.

Since i have been in Paris I have written a dozen short stories, some of them set here, some in Western Kansas, others set one place or another in The Rest of America. I have published them in various magazines and now I am arranging them for a book. The publisher is not a large New York firm, but rather a fine small publisher, and I am grateful for their offer. My name is Leo Murdock, but I use another name for my stories, and now for this book.

What I like about living in Paris is the distance it gives me on America, and paradoxically on Paris itself. I doubt a French writer would feel the same way were he or she to live in New York, and I cannot say why I feel a distance from Paris even as I am living in it. Perhaps if I were fluent in the language that distance would close. Translations of Montaigne help. Also, this from Twain (by my memory): “The French are amazing, even the children speak French.”

The proof for the book of short stories came the other day. The cover is the picture of the Dodge City Cowboy Band—unless I save it for something else. I am to choose the title from one of the stories.

I need to think about it. And a dedication. Maybe a preface.

It has become a late fall or early winter here in Paris. Proust’s memory is triggered by scents. Mine, as it turns out, by memory. The other day I found a bistro that served poule au pot, the flavor of it floating into Place Dauphine. I have not found soupe éternelle. I suppose I could make it myself but I don’t cook here. Instead, I take a coffee and a pain au chocolat at the café where I first met the sad woman in the mink coat. Some days she is there, some days not. The same for me.

It is as if we are avoiding each other in order not to meet one another: A woman out of a Jean Rhys novel probably does not want to step into the fiction of West Jesus Land, Kansas—or even The Rest of America. Nor do I want to be absorbed into Rhys’s triste world of misery and woe, even if she does write better than I do. Here’s not looking for you, kid.