My Son’s Story

I studied journalism with no idea that the most important story I would ever tell would be the tragedy of my own family.

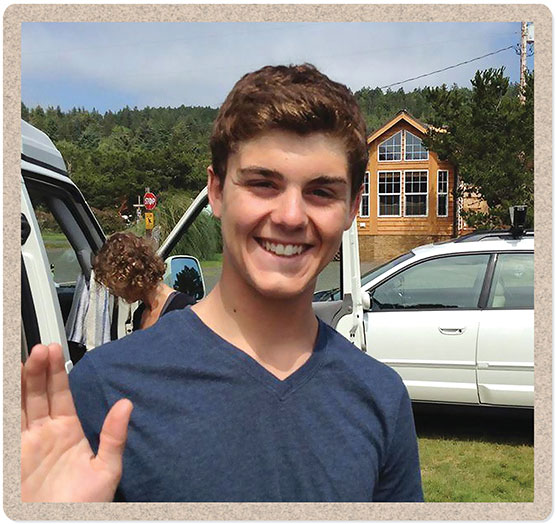

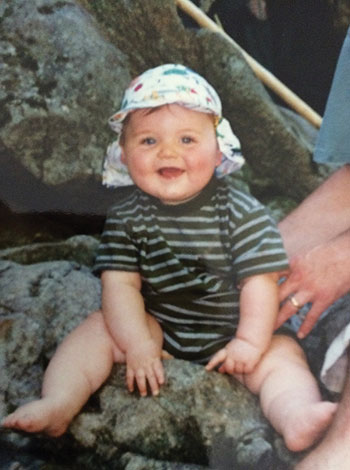

My son, Calvin, was a happy baby, a solid student, a successful athlete. He grew into a clever, curious, compassionate person. He also developed a serious mental illness in his teen years that devolved into psychotic episodes. A mental health care system in disarray meant that instead of helpful care, our family met heartbreak.

In disbelief, I watched my son’s world tilt away from a bright future punctuated by academic accolades and toward incarcerations, suicide attempts and hospitalizations in locked wards that didn’t make him better. Along the way, the everyday bad news cycle got personal. I’m not at all surprised that homelessness and suicide rates are rapidly rising or that so many police encounters end tragically. These are preventable social ills, but our service systems are not built to prevent them.

Families like mine strive to keep loved ones from hitting rock bottom, discovering that there really is no bottom and that help doesn’t prevent but instead requires a radical freefall. I watched my son delivered into society’s underbelly by design. He spent months homeless, met law enforcement again and again, and tried multiple times to die. These traumas are part of a tragic inventory of the requirements for public assistance when someone has a serious mental illness. Calvin was 23 when he died from suicide March 18, 2019.

As I try to reconcile what happened to my son and our family, I have been compelled to dust off my journalism skills to write and holler my way into public view. While I work, the title of a book by Ron Powers spins me like the stanza of an unlikable but unshakeable song: No One Cares About Crazy People.

Powers fathered two sons who developed schizophrenia and lost one to suicide. His book is among a dozen or so by family members whose children have gotten sucked into the void of serious mental illness. I’ve contacted most of those writers, including Pete Earley, who wrote Crazy: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness.

Like Powers, Earley and other families in this fight, I refuse to let people not care.

I also refuse to slink away in despair. When I was new to advocacy, I posted a quote from Anne Frank above my computer: “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.” When I doubt whether my voice will ever matter, I consider that quote, take a breath and get back to work.

I testified in the Washington State Senate for the first time January 18, 2019, when I believed there was still time to influence changes that might save my son. Lawmakers were reconsidering the Involuntary Treatment Act (ITA), a state law that determines criteria for behavioral health intervention. (Washington passed a new ITA law in 2020—see story, “What can be done?” below) My hands were shaking as I held my printed speech. I leaned toward the microphone, made eye contact with the senators and tried not to cry as I began: “ITA law in Washington State traps an individual in an illness state so that the only way out is through violence.”

This statement was not hyperbole. A scene that haunts me still is a night when Calvin was on our back deck in the dark, swinging a large stick and “preaching.” On the patio table he had assembled bizarre altars built with playing cards from the Magic: The Gathering game, sticks and bits of food. He was interacting with unseen individuals, speaking words that were loud but not really intelligible. I encouraged him to come inside. His eyes were wild and dark. He didn’t hit me, but I was afraid when he blocked me with the stick and said, “Stop!” He was there, but not there. As I slipped inside to call for help, his manic raging continued.

The disinterested county crisis responder on the phone suggested I lock my bedroom door and use earplugs to sleep. “It’s not illegal to be psychotic,” she said, clearly reciting something she had said many times. She explained why she wouldn’t do anything to help: “We’re protecting your son’s civil rights.” If he hurts someone or himself, she went on, then call police. I connected the dots in my head: My son had the civil right to avoid the hospital, but protecting that right put him at risk for arrest and possibly jail. To restore him to sanity, we would have to catch him in a narrow window between violence and crime.

There were so many times that the madness of mental illness policy crashed full force into my family. Calvin’s treatment took many wrong turns because of systemic disorganization, discrimination and underfunding. Still, I often circle back to the brokenness of that pivotal moment when we had no idea how to help our super-sick son and were told that violence and crime were the missing elements for intervention. Most infuriating was the smug crisis responder’s position that this lack of help served my son’s best interest— to protect his “civil rights.”

Civil libertarians who might be reading, please settle down. I’m one of you.

I believe in the right to agency and self-determination. What I have learned in the harshest way possible is that when someone is that sick, agency is already gone—stolen by the disease. Involuntary treatment is the only kind. A mind so unwell cannot see its illness or a need for care. A person as sick as Calvin was that night is not saying “no” to treatment but instead is leaning into an alternate reality where Magic: The Gathering characters come to life and the world is on fire with excitement and opportunity. Of course, I suggested we go to the hospital that night. My offer made absolutely no sense to my delusional son.

Years later I learned the term anosognosia—a symptom of brain-based disease when a person is unable to “see” the illness because of disordered connections in the brain itself. When he was symptomatic, Calvin had no idea he was crashing toward disaster. As his mother, I saw clearly what was coming, just like knowing a small child who darts into the street is going to get hit one day. I had no power to prevent any of it.

Even before he could walk, he enjoyed the forests of the Pacific Northwest. Calvin, Jerri and Matt hiked near Lake Sammamish on Christmas Eve 2017. Calvin body surfed in Hawaii in 2016. His tattoo says, “Surf Your Waves.” Courtesy Jerri Clark

I remember a time when happiness and health felt normal. I left Lawrence and my position as an assistant editor for Kansas Alumni in 1995, newly married and five months pregnant. My husband, Matthew Clark, g’92, settled into a career with Hewlett-Packard. I became mother to baby Calvin and Michelle, 10 years older than he. I taught yoga and children’s ballet, work that blended well with parenting. We loved our Pacific Northwest home in Vancouver, Washington, where through the years we surfed off the Oregon coast and skied down Mount Hood.

Calvin became a state-champion debater and earned a scholarship to Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. Midway through his freshman year, he called in a rambling, tearful rant about being abandoned by fellow debaters. The details did not make sense. We brought Calvin home. Well past midnight, on February 16, 2015, I realized my baby boy had lost his mind.

Calvin’s speech was alarmingly disorganized and frantic. He did not sleep and was convinced a bathroom in our house was possessed and should never be entered again. A family doctor prescribed lithium. Calvin was at first relieved to have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, like his paternal grandfather. This explained some of his confusion, so he agreed to take the medication. He got a job at the local farmer’s market selling cookies. He bought a Cookie Monster T-shirt. We were rearranged, but we were a family and happy to be together. There was even a magical day of surfing that spring when we all successfully caught overhead rides.

We came up for air, but the dangerous waves we would try to ride were just setting up. Events in the years to come tossed me around enough to reorder my understanding about what it means to be a parent, a compassionate person and an activist.

That first year ended badly, when Calvin got tired of the jitters and mind fog that were side effects of the medication and stopped taking it. His mind exploded with life plans—tour with a rap band, sponsor a homeless benefit on the lawn of the Oregon Capitol, travel the world, join a commune, become a minister and drive, drive, DRIVE! It was like watching a train speed up just as the track started to crumble. A crash was soon to follow.

Calvin’s disinterested “provider” (medical doctors rarely work with someone this sick—see story, p. 55) warned in a monotone that stopping the medication would be unwise. The choices were up to Calvin, and he felt no motivation to stay in “treatment” when the callings of mania were much more enticing. The first big crash happened in January 2016, when Calvin was hospitalized for suicidal ideation wrapped up in manic psychosis. While he was there, my father died. Jerome Niebaum, d’61, who retired in 2004 after a long KU career in academic computing, died on my 50th birthday, January 5, 2016.

While grieving the death of my dad and my son’s worsening mental health, I found life support from yoga. My practice went beyond physical postures into the philosophical underpinnings. I trained in a meditation technique called iRest (Integrative Restoration), which helped me understand the possibility of being with many emotions at once. I could find joy in the ocean while dripping salty tears onto my longboard. While my dad was in hospice, I wrote a poem for Thanksgiving that ended with this stanza:

The thanks I am giving this year is deep, and dirty. Thank you, world, for showing me what it feels like to be. In all its complexity. The raw, red-eyed reality of love and loss. I am grateful for the opportunity to feel. Grit/Great. Full. Real.

Pema Chodron, a Buddhist nun, advises in one of her books, “Give up hope.” As my son fell through rock bottom, this direction helped. My thoughts formed an essay published by a website for mental-health topics, “Brave Expressions.” Here’s a segment:

I started to consider that giving up hope might help me heal and continue to function. Hope is stuck in the future. Agency is right now. I decided to focus on what I could do instead of waiting with hope for things to sort themselves. I also had to give up hope that doing the right thing would get me what I wanted. Seeking right action was worth it either way.

I started Mothers of the Mentally Ill (MOMI) in May 2018. At the time, Calvin lived in Seattle, unstably housed and often unwell. Calling for crisis intervention always took me back to that earlier phone call, when I learned that being psychotic was “not illegal” and that my son’s civil rights meant he had to be dangerous to get help. He did prove dangerous on several occasions, but hospitals barely kept him long enough for the “imminent” threat to pass.

Calvin’s final arrest happened after a hospital released him into homelessness. After wandering the streets for a week, he hallucinated that he had found his “true home” and broke into a stranger’s apartment through a window. He called his grandmother with the address, wanting her to visit or write. Police already had him in custody when we called 911.

He was incarcerated for six weeks in the downtown Seattle jail. Matt and I had the surreal experience of locking up our personal effects, going through metal detectors and riding a clanky elevator to the seventh floor, where psychiatric inmates were housed. We told our shackled son we loved him, through Plexiglas. His eyes were not tracking. I knew delusions and hallucinatory voices were pulling him deeper inside himself.

Jail is often viewed as a better access point to services than an emergency department. Calvin’s case manager encouraged me to celebrate his incarceration. “This could be good news,” she exclaimed. “Maybe now he can get more help.” These words infuriated me. Somewhere around that time I learned that individuals with severe mental illness are 10 times more likely to be incarcerated than treated in state hospitals.

Calvin’s first incarceration for being sick was while he lived with us in Vancouver, not long after that night on our back deck. Unable to see his illness, Calvin leaned into mania. The highway beckoned. He loaded up with Halloween decorations, cat food and other random items but didn’t fill the car with gas, believing his own energy would be fuel enough. Out of gas with his car halfway onto the shoulder, he was discovered by a law enforcement officer who took him to a hospital for a toxicology test, presuming he was on drugs. Hospital staff determined him to be dangerously unwell and he was detained to a psychiatric facility. The court held a hearing related to the DUI charge and issued a bench warrant when he didn’t show up because of being in the hospital. (Explaining this obvious conflict to the court didn’t matter.) When he was discharged—still unwell—and encountered police, he was taken to jail on the bench warrant.

During that debacle, I joined a support group at the local affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), which became the first place I felt solidarity. I started sharing my story in a NAMI Southwest Washington training, “See Me,” which spreads understanding about psychiatric conditions for first responders and others who encounter the mentally ill in their work. I found myself merging my journalism training with skills I learned judging speech-and-debate contests during Calvin’s high-school days.

As I found my voice, I started to network. A series of contacts led back to Kansas, and a kind NAMI Kansas director was the first person to explain Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) as perhaps the most evidence-based option for outpatient care. That smart tip was frustratingly difficult to apply, as were other snippets of advice that never manifested a coherent strategy. “Evidence-based” doesn’t mean available or well-funded.

Losing my son in such a tragic way has galvanized me to inspect key moments where something could have gone differently. I’m forced to relive our traumas as I unpack them for advocacy. Along the way I’ve decided that happiness isn’t my most important mission.

That’s not to say I haven’t met happy moments through the work. I’ve enjoyed connecting with grassroots advocates nationwide who are moved by their own awful experiences to speak out and demand change. We befriend one another through local networks and social media. Many have united around a pivotal book by D.J. Jaffee, Insane Consequences: How the Mental Health Industry Fails the Mentally Ill. Jaffee, who died in 2020 from cancer, derided systems that promote “mental health for all” over care for the seriously mentally ill.

I read Jaffee’s book while Calvin was in the Seattle jail. I struggled to find a specific direction for my own finger of blame. The governor seemed to oversee most systems that had failed Calvin, so I called Gov. Jay Inslee’s office.

I learned that Inslee preferred to meet with groups. About a dozen friends and I quickly bonded under the name MOMI and met with Inslee for the first time on June 26, 2018. Since then, I have been invited by public officials into work groups and press conferences. Calvin died during the 2019 legislative session, while I was actively testifying on various bills. Lawmakers sent flowers and mentioned Calvin during hearings. The governor has been kind and sent our family a personal letter. At a bill signing, he privately encouraged, “Tend your heart.”

When MOMI began, I sponsored several public forums that got press attention. Austin Jenkins, a reporter from a National Public Radio affiliate in Olympia, interviewed Calvin and me for an Aug. 27, 2018, broadcast. Calvin talked about his first serious suicide attempt, when he jumped from a highway bridge into the Columbia River, and he expressed disbelief that such an extreme cry for help was needed.

Jenkins connected me with Steve Goldbloom, who produces “Brief but Spectacular” for PBS NewsHour. Goldbloom interviewed me for a segment that aired Jan. 11, 2019. On March 21, three days after Calvin’s death, anchor Judy Woodruff honored Calvin on the show.

My work to help scaffold mental health care and detangle it from homelessness and criminal justice has put me on legislative work groups, advisory committees, coalitions and more. The day after the second anniversary of Calvin’s death, I testified in the Senate Subcommittee on Behavioral Health. The lawmakers were considering a bill to improve the state’s crisis response system as part of implementing a new 988 behavioral health crisis line. The 988 number goes live nationally in July 2022 to replace the hard-to-remember National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255).

Washington passed HB 1477 to establish the 988 system. I will press to participate in a work group that will oversee how that goes. My March 19, 2021, testimony included a key story from Calvin’s life: “In the spring of 2018, my son’s landlord in West Seattle called with grave concerns. Calvin was bizarrely confrontational with other tenants in the house where we paid to rent him a room. He had dug up the landlord’s garden and would scream and mutter in the street. They wanted to evict our son but also were kind people who wanted to make sure he was OK. The landlord asked me what she should do next. Should she call the county?”

In my testimony, I described the confusion about which number to call, what to demand, and how that entire process of “crisis response” took more than a week.

“The crisis system requires a severe level of illness,” I said to lawmakers, “yet responds in a slow, underserved and disorganized manner.”

The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 5% of the U.S. population experiences serious mental illness (SMI), which severely impairs daily living. Common SMI diagnoses are schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The 2019 data estimate that only 65% of individuals with SMI received treatment, and those numbers do not capture detail about treatment scope or outcomes.

Shortly after Calvin’s death, a great horned owl swooped low over my head and landed in a treetop nearby. We gazed at each other for several minutes before he flew away. In this grieving moment, I believed I was experiencing something spiritual. I told my cousins about it on the day of Calvin’s memorial service. At twilight, we stood in my backyard garden, which backs up to the wooded greenspace where I first saw the owl. A cousin asked why I believed the owl carried a message from Calvin. Because, I said, with awe and wonder, “He’s right there!” In that moment, a great horned owl flew by, low and closer than I have ever seen.

Owl iconography seems to find me. In a town hall to discuss mental health care access, an owl mural adorned a wall. A fellow parent giving testimony had an owl tattooed on her arm. Sitting down with a state senator, I noted an owl calendar in her office. I have the wisdom to know this is the story I am responsible to keep telling. Calvin’s spirit guides me.

Jerri Niebaum Clark, j’88, works from her home in Vancouver as a resource coordinator for PAVE, a Washington State nonprofit organization that supports families dealing with disability. She is grandma to two little boys.

A call for Kansas photographs

Serious mental illness policies and priorities

Here are a few key learnings from my long, strange trip through the chaos of mental illness law, policy and practice:

The private-pay medical system fails to serve really sick people. During my son’s first year of illness, 2015, I called 25 to 30 psychiatrists and was turned down by all but one, who offered an appointment in nine months. The insurance network provided a list, but most refused care or were retiring.

State insurance is better and covers some case management, but a determination of disability is required if an individual is not eligible based on income. Getting Social Security took years, with multiple appeals. Calvin’s initial access to Medicaid happened in tragic, traumatic fashion when he was arrested and involuntarily hospitalized. His discharge included a court order for public-health case management, so the hospital fast-tracked his Medicaid application.

Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) is the highest-level of outpatient care in Washington, but it’s a fail-first model. Calvin’s eligibility was determined from a history that listed jail time, homelessness, involuntary hospitalizations, suicide attempts and state commitment. He completed that tragic inventory too late, qualifying for PACT with housing six months before he killed himself. Another helpful option would have been Assisted Outpatient Treatment, a therapeutic court protocol for helping individuals with persistent, disabling mental health conditions maintain stability and/or sobriety.

Calvin’s symptoms included anosognosia, which presents as lack of illness awareness. A person with this symptom is not in denial; the brain is blocked from seeing its impairment. This symptom can occur due to stroke or brain injury and is present in many patients with the most severe forms of mental illness, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Dr. Xavier Amador’s book, I’m Not Sick, I Don’t Need Help, taught me about this complication, which was never explained by providers.

States have a variety of laws to “protect” individuals unable to care for themselves due to psychiatric impairment. Most Involuntary Treatment Act (ITA) laws rely on a standard of “imminent threat.” In other words, they require violence. Our family learned this in the harshest ways possible, and this issue feeds controversy about the role of police in deciding what to do when someone finally gets sick enough to meet a threshold for commitment. I testified to support a new Washington State ITA law that lowers the threshold a modicum for someone who is “gravely disabled” due to mental impairment. The new law might save lives. My testimony began, “My son met criteria for involuntary treatment the moment that he stepped off the roof of a hotel and fell to his death.”

Advocacy families are coalescing to promote a national agenda, which is included in the appendix to Tomorrow Was Yesterday, by Dede Ranahan and 64 co-authors, including me. One goal is to lobby Congress to repeal a 1965 law that forbids Medicaid reimbursement for inpatient stays at psychiatric hospitals with more than 16 beds, known as Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD). Intended to discourage institutionalization, the IMD Exclusion instead has resulted in fewer hospital beds for treatment, leaving more people with mental illness unhoused or incarcerated. The pandemic has worsened their plight.

From the start of his illness, Calvin wanted to live independently. Unfortunately, he was too sick to do that safely. There is no pathway into supportive housing that does not include significant time spent on the streets; homelessness is required, not prevented. I remember a night in October 2017 when Calvin called from a copse of trees near the University of Washington campus. He was wrapped in a tent we had used for camping before he was born. He had lost the poles and his coat. Using the cell phone that was still on our family plan, he called to say goodnight. “I love you to the moon and back,” I told him, before crying myself to sleep. No system would help unless I let this disaster play out. I have recently joined the steering committee of Hope Street Coalition, led by Paul Webster, a former director at the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We are shining light on the unsheltered mentally ill and the changes needed to reverse this humanitarian crisis.