Fossil guide evolves

Digital Atlas of Ancient Life adds Android app, Cretaceous specimens

Fossil hunters of all ages—and smartphone preferences—now can use a new and improved digital field guide, thanks to a KU-led team of scholars.

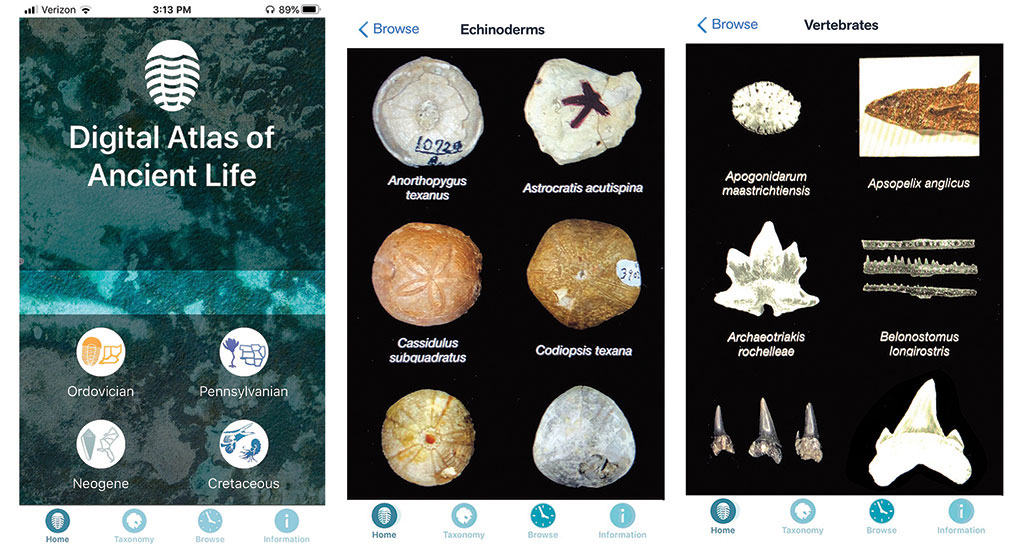

Researchers at the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum in December released Version 2.0 of the Digital Atlas of Ancient Life, a smartphone app now available to Android users. The first rendition of the app, released in 2015, worked only on iPhones.

The digital atlas continues KU’s quest to share the millions of specimens in its collections, not only with fellow scholars but also with everyday discoverers who yearn to know more about the natural world.

“Our collections have great importance for scientific research, and we make sure our data is available to scholars, but we recognize that many people are fascinated by the natural world around them,” says Bruce Lieberman, senior curator at the institute and professor of ecology & evolutionary biology. “We can give them the opportunity to see things that are still locked in cabinets, and that’s a huge advantage.”

Lieberman, who joined the KU faculty in 1998, leads the atlas project, which began with a National Science Foundation grant to launch the Digital Atlas of Ancient Life website in 2014. He collaborated with Jonathan Hendricks of the Paleontological Research Institution in Ithaca, New York, and colleagues from several universities to gather digital images of specimens from their combined collections. A mobile version was the natural next step. “People typically don’t have web connections when they’re out finding fossils; they need something when they’re out in the field,” Lieberman says.

Two additional NSF grants supported the 2015 release of the first mobile app and Version 2.0. Although the first app was available only for iPhones, it garnered 7,500 active users in the United States, Canada and beyond. In only one month since Version 2.0 made its debut, more than 1,750 users downloaded the tool, Lieberman says.

The improved app features 30% more content, including 500 new species from the Cretaceous period (which began 145 million years ago and ended 66 million years ago), along with maps of collection sites in Kansas and regions throughout North America. The first version of the app focused on invertebrate fossils; Lieberman says users of the new app are especially pleased that the additional Cretaceous specimens include fossil vertebrates, primarily from the Western Interior Seaway that covered Kansas and neighboring states. “People seem really psyched about sharks’ teeth,” he says.

The digital atlas team also includes Rod Spears, who built the program infrastructure for the mobile app. Spears previously worked at the KU Biodiversity Institute to create Specify, the software used by museums worldwide to share data from their collections. Zach Spears refined the design for the new mobile app, which features crisp, high-resolution images and easy navigation.

Users can browse specimens from the Cretaceous period; the Ordovician, which began 488 million years ago and ended 443 million years ago; Pennsylvanian, 318 to 299 million years ago; and Neogene, 23 to 2.6 million years ago. The images lead to facts about fossils’ geographic distribution and taxonomy. If proposals for continued grant support succeed, the team plans to add more geologic time periods and geographic regions to the app.

Though the mobile digital atlas is a welcome resource for paleontologists and other scholars, Lieberman and his colleagues hope to promote curiosity and exploration among K-12 teachers and their students and anyone interested in fossils, especially in Kansas, a region rich in specimens.

“Kansans are intuitively inquisitive about the natural world,” he says. “We have a real connection to the land because of the importance of agriculture, and we live in a state that has large amounts of countryside, even near big cities like Kansas City. There are lots of rock exposures, so people naturally come into contact with fossils.”

Though he cautions fossil hunters to steer clear of highways and busy roads, where collecting is illegal, Lieberman says there are countless opportunities to find specimens along local roads and trails. “They are anyplace where you see rocks that outcrop, especially the yellow rocks,” he says. “Those are going to be packed with fossils.

“Someone could walk up to a rock and pick up a shell that lived 290 million years ago under a gentle shallow sea.”

Fossil app at a glance: