Reggie Burrows Hodges: Snapshot and memory

Remembered scenes of childhood and images of sport draw artist Hodges’ watchful eye.

By the art world standards that most easily catch the general public’s eye, painter Reggie Burrows Hodges has been on a roll lately.

Hodges, ’89, won prestigious fellowships and prizes from the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation, in 2019; the Joan Mitchell Foundation, in 2020; and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, in 2021.

He landed solo exhibitions in New York City (January through March 2021 at Karma gallery) and Rockland, Maine (May 28 through Sept. 11 at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art).

His work has been acquired by prominent museums across the country, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Art Institute of Chicago, and by famous collectors. Among those buying Hodges’ paintings at the Karma exhibition were Barack and Michelle Obama.

Hodges has also grabbed headlines for his paintings’ performance at auction. During a 2021 sale at Phillips, the 226-year-old London auction house, his painting “For the Greater Good” was estimated at $40,000 to $70,000 but sold for more than $600,000.

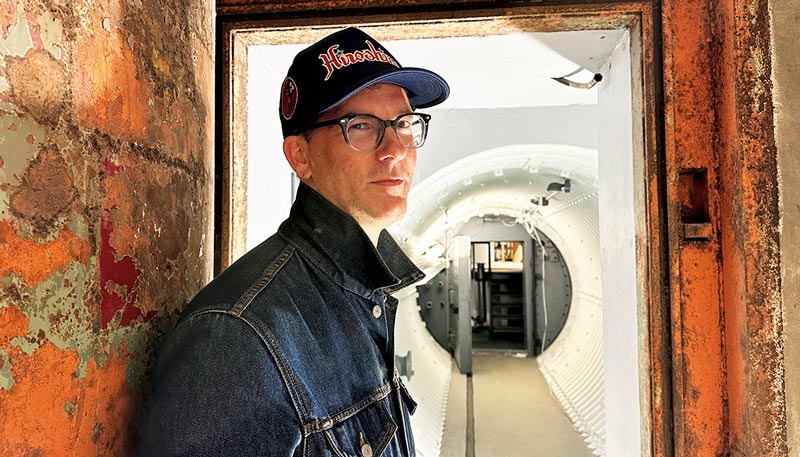

All wonderful—and unusual, for an artist in his mid-50s—says Timothy Peterson, executive director and chief curator at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA).

“His career has hit incredible heights, with a growing waiting list for his works,” Peterson says. “They have entered into museum collections coast to coast all within the last two or three years, which doesn’t often happen for artists in their 50s.”

But more noteworthy in Hodges’ breakout as an artist is the creative breakthrough that underlies all that attention.

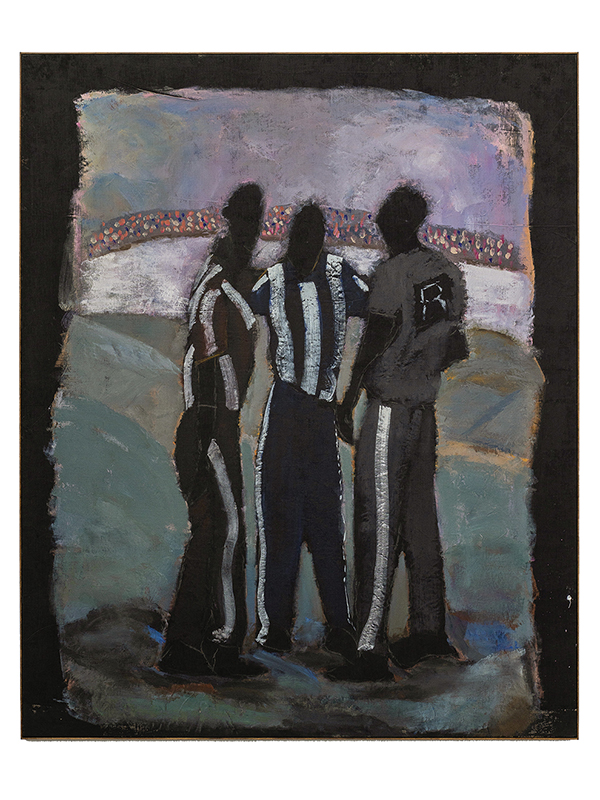

“What’s really special about his painting is that he starts by painting his entire ground black,” explains Peterson, who worked with Hodges to shape “Hawkeye,” the artist’s first museum solo show. “Whether it’s canvas or linen or paper he’s working on, he paints the entire surface black and then paints everything but the exposed skin and hair of his subjects.”

The technique creates an almost ghostly effect, in which the faces of the African American artist’s Black subjects are featureless but nevertheless riveting. The facelessness of the people in the paintings directs the viewer’s attention to their surroundings.

“Blackness remains a very powerfully spoken- about identity really shaped through the attention paid to the environment around his figures,” Peterson says. “He is really painting in a way that is commenting on Black identity within an environment. That is not an easy thing to capture visually, and he has found a way to do it over and over again in a really compelling way.”

Hodges grew up in Compton, California, and attended KU on a tennis scholarship, studying in the theatre department. After a stint in New York City, where he founded the reggae band Trumystic, he moved to Maine, where he lives now in Lewiston. He is an adjunct instructor at the Maine College of Art and Design.

The artist is not granting interviews and did not do a gallery talk in conjunction with the CMCA exhibition. But in an interview with Suzette McAvoy, former CMCA executive director, that appeared in her 2021 monograph Reggie Burrows Hodges, he said that his embrace of a black background was the result of a conscious decision to change the way he paints.

“When I arrived at the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation, I knew that I wanted to break out of where I was as a painter and use this incubation time to land somewhere different, to be able to paint differently than when I came in,” he said, referring to a residency he completed from fall 2019 to winter 2020. “Through a lot of experimentation, I arrived at the language of the black ground, specifically in a painting called ‘The Red Umbrella.’”

Hilton Als, a critic and New Yorker staff writer who has written extensively about Hodges, argues that the people in Hodges’ narrative figurative compositions “are made sharper, and more haunting, not because we see … things in their eyes, but because we see it in their bodies, their postures, the endless desire for humans not to be alone, and to connect.”

The dozen paintings in the CMCA exhibition are large canvases, and the scenes they present are a mix of memories from Hodges’ childhood and images from sporting events. The common theme of these disparate subjects is surveillance. In the huddled basketball referees conferring on a call, the parents supervising their playing children, there’s a sense of being watched over, Peterson says.

“Much of Reggie’s work has to do with memory, and there are portraits of his parents in this exhibition, portraits of himself as a child, but I think the new element in this exhibition is the idea of surveillance.”

That theme comes out in three paintings that reference Hawk-Eye, a tennis surveillance system that uses computer-linked cameras to generate replays that line judges use to check if a shot was in or out. Close-cropped images of bouncing tennis balls, their round shapes elongated by the force of impact, juxtaposed against the truncated geometry of a tennis court’s green and pink surface and white boundary lines create an abstract effect that’s new to Hodges’ work, Peterson says. Yet even here the artist is dealing in recognizable scenes—recognizable, at least, to anyone who watches tennis on TV.

The black ground, tightly contained within the oblong shapes of the balls, gets freer rein in the nine paintings that depict childhood memories. In those nine works, the black ground is used not only to depict faces, but also as a framing device for the entire painting, a softly brushed border that applies—as the exhibition notes, co-written by Hodges and Peterson, phrase it—“a light touch to snapshots of the past, rendering them hazy and indistinct.” Like the soft focus sometimes applied to flashback movie scenes, the technique is a signal to the viewer that this recounting of the past is personal, not documentary.

We are shaped not only by our environment, these paintings seem to say, but also by our imperfect memory of it.

“Referees: And Then There Were Three,” 2020, and “Fault,” 2021, were among the dozen recent Reggie Burrows Hodges’ works featured in “Hawkeye,” the artist’s first museum solo exhibition. View the exhibition online at cmcanow.org/virtual-tours. Photographs courtesy CMCA.

RELATED ARTICLES

/