Life, amplified: Audiologist shares hearing loss experience

Issue 4, 2023

Jessica Whitfill Johnson suspected she was missing out. Although the sociable 24-year-old was frequently in the company of friends, classmates and co-workers, sharing in the spontaneous magic of conversation often proved elusive. The world seemed muffled by an invisible barrier that kept genuine connection and all of its joys just out of reach.

“I would try to be a part of conversations, but I was bluffing,” recalls Johnson, c’17, AUD’21, now 28. “I’d laugh along when other people were laughing, but I didn’t know what the joke was. I’d completely missed the joke because I couldn’t hear it.”

The feeling was, unfortunately, familiar. Born with an atypical right ear, Johnson had first experienced hearing loss even earlier in her life. She began using a hearing aid at 14, and while the technology saw her through high school and her undergraduate years at KU, by the time she was a student in the University’s doctor of audiology program, it was no longer powerful enough to overcome her hearing deficit.

“My hearing loss had progressed, and for a long time I had quite a bit of social anxiety,” she says. “I think a lot of it stemmed from being fearful of saying the wrong thing or laughing at the wrong time or responding inappropriately to a question because I couldn’t hear it. It was very isolating.”

Today, thanks to a hearing implant, Johnson has a full range of hearing, and equipped with her KU degrees, she is often a first refuge for others struggling with hearing difficulties. Her own experience allows her to offer both care and compassion.

“I understand what they’re going through on a personal level, and I think a lot of patients appreciate that,” says Johnson, who practices at American Hearing + Audiology in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Being able to spend my career helping people hear better when that’s what I needed myself—it makes me feel so fulfilled.”

Johnson was born with microtia, a condition that caused her right ear to be small and malformed. “With microtia, I was essentially born without an ear canal, and then the tiny little bones in the middle ear, called the ossicles, weren’t structured properly,” Johnson says. Microtia commonly results in conductive hearing loss, which occurs when sound can’t be effectively transmitted into the cochlea, the hearing-sense organ in the inner ear.

Doctors informed Johnson’s parents, Charles and Kindra Whitfill, that her right ear’s inner components functioned well, and that a series of surgeries—best started at age 6—to open up her ear canal and restructure the middle ear bones could counter the hearing loss.

As Johnson grew from an easygoing baby to a thoughtful young girl, the Whitfills weighed the decision and worked to instill in their daughter confidence around communication. “Raising her, we made it a priority to make sure she understood conversations, and we taught her to ask, ‘Can you repeat that?’ if there was something she didn’t hear,” says her mom, Kindra. “We worried that her hearing loss would have social effects, but for Jessica it never did. She was always very active, always trying new things.”

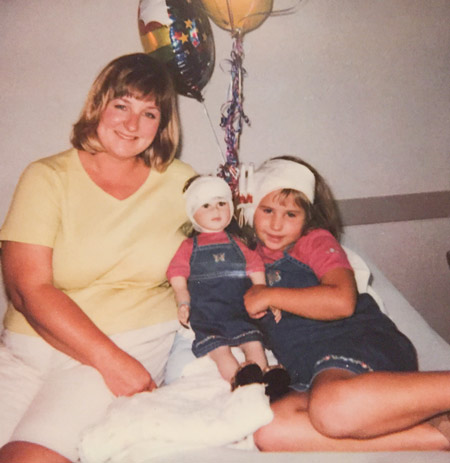

Still, the Whitfills wanted to take every step to ensure Johnson’s hearing loss wouldn’t hold her back as she got older. They opted to move forward with surgery, and from age 6 to 9, Johnson underwent nine procedures to restructure her outer and middle right ear.

Johnson didn’t detect any trouble with her hearing during her younger years, but by the time she was in high school—in Wichita, after growing up throughout the Midwest as her dad completed his training as a physician—she’d begun to notice gaps in her perception. “When I was little, I think I just kind of got by. I probably wasn’t paying much attention to it,” Johnson recalls. “But in middle school and high school, the auditory environments we’re in get much more complex. I have this distinct memory of being in high school and my friends telling me they would yell my name down the hallway, and I just flat out couldn’t hear them. I’d have no idea they were trying to get my attention.”

A hearing test at 14 confirmed Johnson’s hearing in her right ear wasn’t at full capacity. Her audiologist presented two courses of action: more surgery or a hearing aid. Johnson chose the hearing aid, and the device’s immediate impact left an impression.

“I remember it was fall, and I could hear the leaves rustling the first day I got my hearing aid,” she says. “I wasn’t sure what the sound was, and I remember having to ask my mom.” It’s a memory she shares frequently today when fitting patients with their first hearing aids, to prepare them for the minute sounds that may suddenly surface. “Most hearing loss typically comes on so gradually that people don’t notice it’s gone until they get tested, someone tells them it’s gone, and they get fitted with a hearing aid,” Johnson says. “My patients will say things like, ‘I had no idea the turn signal in my car made a noise.’”

Johnson’s enhanced hearing transformed her time in high school. “Participating and following along in class became so much easier,” she says. “I could hear the conversation at the lunch table. I could hear what was going on when we broke into groups in class. I could hear my friends whisper to me.” Singing in choir, a favorite activity, was no longer an exercise in guesswork. “It was a little bit easier when I could hear my cue to come in,” she jokes. “I did a lot better in choir after that.”

A diligent student, Johnson set her sights on college and ultimately decided to follow in the footsteps of her big sister, Madelyn, d’15, and attend KU. Her next chapter would bring a rewarding career path into focus and an old obstacle back to the forefront.

When she arrived on Mount Oread in fall 2013, Johnson was undecided on her major. One day, casually discussing her options on the phone with her mom, the conversation turned to audiology.

“I remember my mom saying, ‘What about audiology? You know what it’s like to have hearing loss.’ And my first thought was, ‘Why would I do that, Mom?’” Johnson laughs. The suggestion stuck, however, and the following semester, Johnson took the introductory course in the department of speech-language-hearing, part of the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences. The class, particularly the section about the ear, intrigued her.

“Ears and hearing aren’t things we think about a whole lot,” Johnson says. “For me, I think my fascination with the ear probably came from the fact that I didn’t grow up having two normal ears. In a sense, I understood that I was born with microtia and that I had hearing loss, but I didn’t know how the whole system worked, where the breakdown was exactly. So learning about this very complex organ that has a very fine-tuned way of working was so fascinating to me. I declared my major after I took that class.”

She earned her bachelor’s degree in speech-language-hearing and started her graduate work in August 2017. In KU’s doctor of audiology program, her affinity for ears and their functioning broadened into a passion for working with patients. “I remember coming home after my first couple of days of clinical rotations and being so excited,” she says. “I loved every moment of it, and I remember thinking, ‘This is how I know I’m supposed to be doing this.’”

When Johnson was about midway through the four-year program, she began to suspect her hearing ability had regressed. Keeping up with conversations had become increasingly difficult, and everyday sounds had slowly dulled. She asked a classmate to test her hearing, and discovered that even with her hearing aid, her hearing was again not at full capacity. Her unique external ear structure from her surgeries limited her options for hearing aids.

In a serendipitous turn, Johnson was taking the class on hearing implants around the time her hearing loss reemerged. She learned about a system made by the brand Cochlear called the Osia. It consists of two parts, an implant and an external sound processor. The implant is positioned behind the ear, just under the skin. The sound processor, held to the implant via magnetic connection, converts sound to a digital signal, which the implant uses to generate mechanical vibrations. To Johnson, it seemed the perfect solution. “The implant sends vibrations to the inner ear, the cochlea, and I’ve got normal hearing there,” she says. “All my hearing loss is in the middle and outer ear structures. So the implant bypasses everything that doesn’t work properly.”

Her professor pointed her toward specialists in the Kansas City area, and in September 2020, Johnson had her hearing implant placed. When her doctor activated the sound processor a month later, the difference surprised her.

“The first couple of weeks, I was amazed and somewhat baffled at how much better I could hear,” she says. “I was working full time in my residency, and I remember people calling my name down the hall in the clinic, and I could hear them. That was a bizarre experience for me. Going out to restaurants and group gatherings in general, I didn’t have to struggle and stress and strain to hear what people were saying. I could finally be a part of the conversation again.”

She graduated with her doctor of audiology degree in spring 2021 and began working at an ear, nose and throat practice in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. She joined the American Hearing + Audiology clinic in Tulsa in March 2022.

Johnson evaluates patients for hearing loss, tinnitus—a ringing in the ear—and a condition called auditory processing disorder, which relates to the brain’s interpretation of sounds. She also sees patients for hearing aid fittings and checks. Empathy and problem-solving are at the heart of her practice.

“One of my biggest goals is to make sure that every patient feels like they’ve been heard and that they’ve gotten answers to what they came in asking,” she says. “In the medical world, sometimes we can feel like we’re just another number, just another patient getting pushed through the system, so it’s important to me that patients know I’m always going to do my best to get them hearing better, to get them more relief from their tinnitus, to give them the right recommendations for their auditory processing disorder.”

Empowerment around hearing is another emphasis for Johnson. “You have every right to advocate for yourself and let your friends and family and those around you know what you need from them in order to be able to communicate,” she says. “That’s one of the takeaways I hope my patients get: that it’s OK to ask somebody to repeat themselves. You don’t have to fake your way through a conversation just so you don’t make the other person uncomfortable—because they’ll get over it,” she laughs.

She hopes, too, for a shift in attitudes toward hearing loss and assistive technology. “When people have unclear vision, they go get their eyes checked and get glasses, and it’s not a big deal,” Johnson says. “My hope is that people who struggle with their hearing go to the audiologist and get hearing aids, and it’s not seen as a big deal.”

Since getting her hearing implant, Johnson has volunteered as a resource for others considering the Cochlear Osia system. She meets with prospective users virtually to talk with them about the process and answer their questions. “I feel like I get to, in a way, calm their fears, give them a better picture of what surgery looks like, what recovery looked like for me, and what it’s like to hear through an implant, which is kind of an abstract thing to try to explain to people,” she says.

She lives in Tulsa with her husband, Luke, and their dogs, Lucky, Lando and Lily. Outside of work, she enjoys reading, crafting and live music, and delights in the little pleasures her better hearing affords her: listening to birds chirping, the breeze through the trees, wind chimes dancing.

For Johnson, her path epitomizes a lighthearted lesson—“Sometimes mom is right!”—and is a testament to the satisfaction that comes from heeding one’s calling. “The saying, ‘If you find something you love, you’ll never work a day in your life’—that’s how audiology has been for me,” she says.

Equally evident in her story are themes of resilience and purpose. “You can persevere through anything,” Johnson says. “Even if you go through something difficult or feel very different from other people, you can learn and grow from that experience, and can even build a career and a whole life out of it. It doesn’t have to be something that shapes you negatively.”

KU audiology: A distinguished program

The audiology profession, which focuses on the evaluation and treatment of hearing and balance disorders, is relatively young, having emerged in the 1940s when soldiers returned home from World War II with hearing loss. KU’s audiology program began at KU Medical Center in the late 1940s and was among the first in the nation.

“When the disciplines of audiology and speech pathology were established enough that there was a credentialing body, KU was the very first program to be accredited in both,” says Tiffany Johnson, associate professor of audiology and chair of the department of hearing and speech at KU Medical Center. “So our accreditation number is 1.”

Today, KU’s doctor of audiology degree is part of the intercampus program in communicative disorders, which comprises audiology and speech pathology and brings together faculty from the Lawrence campus and KU Medical Center to teach in the graduate programs. Students on the four-year audiology track complete rotations in a network of 36 clinics in the Greater Kansas City area. “We want students to get exposure across the scope of the profession, because they often don’t really know what they’re going to enjoy doing,” Johnson says. “So it’s to their benefit to try all of it out.”

Lauren Mann, AUD’11, PhD’21, clinical associate professor of audiology and director of the neuroaudiology clinic in The University of Kansas Health System, says such variety gives students valuable insight into audiology’s wealth of professional possibilities. “An audiologist might work in a school, in a hospital, a private practice, a VA system, a research setting,” Mann says. “A lot of people won’t have the same job throughout their career, and it’s cool to see when students graduate, all the different shapes their careers take over time.”

U.S. News & World Report consistently ranks KU’s audiology program in the top 10 at public universities, and Johnson credits alumni for adding to the distinction. “We have a lot of students who stay in the area, but we also have people who go around the country and around the world to work, teach and research. I think people interact with them and see how well prepared they are, and that contributes to the rankings—the quality of the students who graduate from this program.”

Megan Hirt, c’08, j’08, is assistant editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Portraits by Charlie Neuenschwander

/