At long last: ‘The Jayhawk’ presents definitive mascot history

Issue 4, 2023

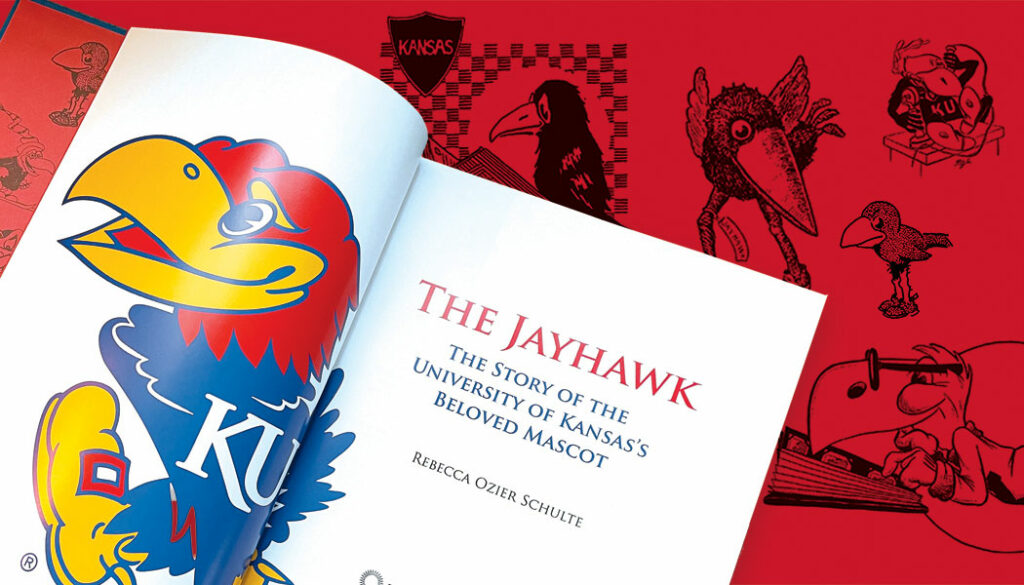

Good news and bad news, Jayhawks: You have homework, but your fun and fascinating reading assignment is the first comprehensive history of our jaunty bird, published in September by University Press of Kansas. So, just to test our Jayhawk knowledge, let’s start with a pop quiz.

The term “Jayhawk” was created and first used by:

a) Free-state fighters, known for their bravado and signature red leggings, who patrolled Kansas Territory’s border counties

b) Chancellor Francis Snow, who joined KU’s first faculty as professor of mathematics and natural sciences

c) Irish immigrant Patrick Devlin

d) Texas immigrant Don Fambrough

Those of you already aware of our University and state’s early days might understandably have chosen a), the border fighters, legendary figures prominent in the pride we take in proto-Kansans fighting the good fight. Some of you deep readers might have circled c), free-state Jayhawk Pat Devlin, “arguably the most important person in the history of the term,” as he’s described by author Rebecca Ozier Schulte in her magnificent new book, The Jayhawk: The Story of the University of Kansas’s Beloved Mascot. b) Chancellor Snow and d) Coach Fam are good guesses in most KU history quizzes, but not this one.

With apologies for the trickeration, the correct answer is: e) none of the above.

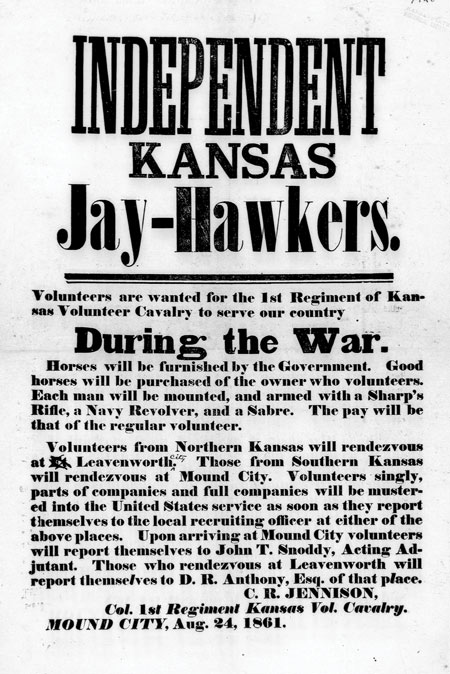

As Schulte, c’76, tells us at the outset of The Jayhawk, “Documented references trace the first use of the term ‘jayhawker’ to the California gold rush of 1848.” Citing The Jayhawkers’ Oath and Other Sketches, by William Lewis Manly, Schulte writes that “jayhawk” appears to have originated among fortune-seekers whom Manly joined on the trek from Illinois to California. As the company of men crossed the Missouri River near current-day Omaha, Nebraska, and navigated the vast Great Plains via the Platte Valley, “it occurred to them that their caravan should have a name, and then and there they dubbed themselves the ‘Jayhawkers,’” Manly wrote, as shared by Schulte.

So it seems we can be fairly certain about the who, when and where of the birth of “Jayhawk.” And yet, Schulte says, “It doesn’t explain why they decided to call themselves ‘Jayhawkers.’”

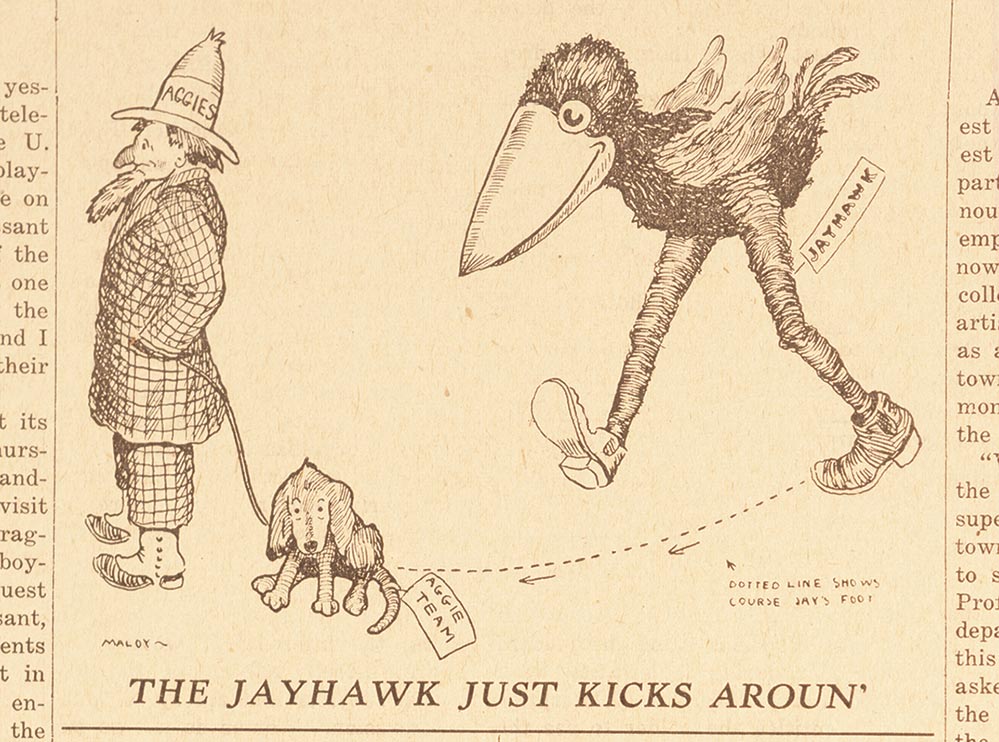

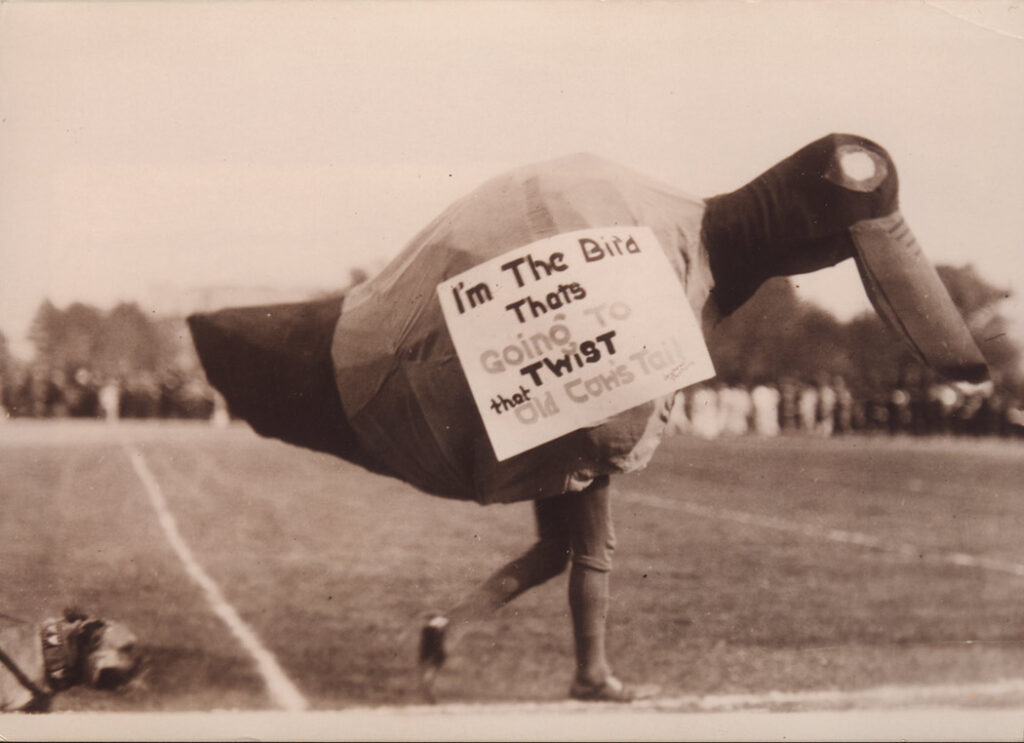

Such are the mysterious voids of history left undocumented while still fresh, the gaps Schulte sought to bridge in her quest to uncover true stories of our mythical bird. Alas, no chancellor ever issued a decree stating, “As of today and forevermore, the Jayhawk is our University mascot!” No 19th-century marketing committee pronounced, “And this is how our new mascot shall look!” And of the countless Jayhawks drawn by spirited artists over the decades, how did a select lineup of six, beginning in 1912, somehow become the officially sanctioned Jayhawk roster?

And yet the haziness, it turns out, is the good stuff. As with all things crimson and blue, the reward is in the long path of discovery that leads to knowledge, appreciation and delight, while also proving endlessly entertaining.

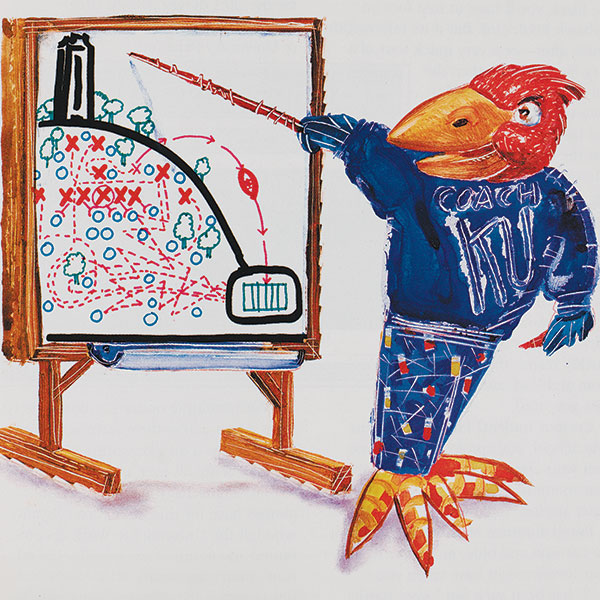

“I tried to have representation of the different decades,” Schulte says of her bold, beautiful book. “It really does take you though the history of the University, and I think people will find that interesting on a lot of different levels. And even for children, it’s very colorful, there are a lot of cartoons, and there’s a little bit of history mixed in here and there. You know, kids might think that’s cool.”

It seems somewhere in the neighborhood of accurate that every journalist, artist, designer, photographer, marketer, songwriter, librarian, blogging historian or public-facing phone-call-and-email answerer in the past century of KU’s existence has dealt, in one way or another, with Jayhawk history and lore.

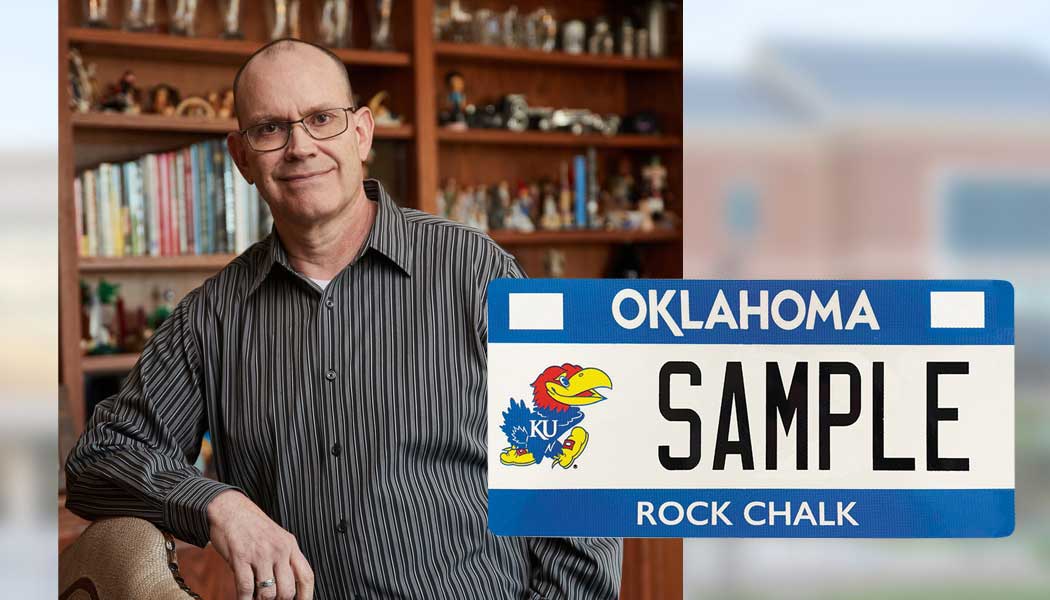

Those of us who have long sweated the details and yearned that someone might one day do the heavy lifting required to preserve, protect and defend the history of such a critical element of our collective heritage should all be thankful that the task fell to Becky Schulte, KU’s third University Archivist, who also happens to be the niece of KU’s first University Archivist, John Nugent, her late uncle and brief landlord.

After beginning her higher education at Labette Community College, in her hometown of Parsons, Schulte transferred to KU as a 19-year-old junior. She was the eldest of nine children, and her family had no money for frills—“We were very poor,” Schulte recalls. “I wasn’t going to be living in a sorority”—so she roomed her first year in Lawrence with Uncle John and his family.

Perhaps following his lead but certainly with no eye toward a career path, Schulte worked as a student assistant in Watson Library’s reserve room while majoring in Renaissance humanities. Mutual friends introduced her in December 1974 to fellow student Dan Schulte, c’76, g’84, and they married the following June.

As was typical of the culture of the times, Schulte immersed herself in her studies while giving no thought to her career prospects. “A big blank,” she says. “Zero.” After her 1976 graduation, Dan was already in graduate school, so Schulte applied for a KU Libraries job as clerk typist II, which, at the time, required taking the state’s civil service exam and a typing test—only one of which she passed. “I think I can type only 32 words a minute, with mistakes.” Schulte instead applied for a clerk II job—sans typing—and began her full-time career with KU Libraries.

Schulte realized within a few years that she wanted to be an actual librarian, so, driving north with a friend who was studying for a doctorate in Madison, she visited the library sciences school at the University of Wisconsin. Schulte and her young family—including their 18-month-old daughter, Emily—in 1981 moved to Madison. After she earned her master’s in library science, they returned to Kansas, where Schulte found work at the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka.

With Dan working in Kansas City, the family struggled to afford day care for Emily and her younger sister, Lizzie, so Schulte in November 1985 returned to KU Libraries to manage a $250,000 U.S. Department of Education grant to catalog the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements, an important holding of the Spencer Research Library. When Spencer Librarian William J. Crowe in 2000 reorganized the research library, he named Schulte the first head of public services, and in 2003 Crowe promoted Schulte to University Archivist.

Six years later, the Alumni Association and KU Libraries hit upon the idea of delivering history-related content at nationwide alumni gatherings. Alumni leaders hoped to generate interest and boost attendance, while KU Libraries—which has long bemoaned the fact that while everybody uses the library, nobody graduates from the library—was eager to spark within alumni fond memories of, and appreciation for, KU Libraries’ crucial role in their education.

Schulte recalls that it was Rebecca Smith, then director of communications and advancement at KU Libraries, who suggested she prepare a presentation on the history of the Jayhawk.

“I knew that we had hundreds of photos, tons of journal articles and little bits and pieces of this and that, and the yearbooks are, of course, full of Jayhawks,” Schulte says. “And so it seemed very doable. I created my first PowerPoint and we took it on the road. It was our way of showing that the libraries had content—interesting content—and not only books. People think the library is just a building with books in it, and an archive is even further away from that.”

In the basement of a Chicago bar where the Association regularly hosted alumni events, an alumna pulled Schulte aside and suggested she write a book.

“I remember thinking, ‘Yeah, the last thing I need is to write a book, for heaven’s sake. I have so much to do!’ But, I guess, maybe, you know, a seed was planted.”

As part of her required faculty research duties, Schulte secured small grants to visit archives at Kansas State, Nebraska and Missouri, where she hoped to learn how other schools portrayed the Jayhawk. (It was in Manhattan where Schulte first came across documentation confirming that, for a time in the state’s early history, all Kansans, even those fiercely loyal to K-State, considered themselves “Jayhawks.”) Along the way, Schulte sensed a book project taking hold.

“I was getting closer and closer to retirement,” Schulte says, “and I think I just felt like I needed to get some of this cumulative knowledge that has come down through the generations compiled in a format that people would enjoy.”

In 2014 she pitched her idea to University Press of Kansas. And UPK declined, reasoning, understandably, that the audience for such an undertaking would be too localized to justify its expense. Schulte recalls that it was probably 2017 when Joyce Harrison, UPK’s then-new editor in chief, visited KU Libraries to deliver a presentation on how to get published.

“So I made an appointment to talk to her,” Schulte says, “and when I read her my idea, she said, ‘That sounds wonderful!’ She was really excited.”

Schulte applied for a research sabbatical, and in 2020 stepped down as University Archivist to work part time as curator of the Wilcox Collection while writing her book. She fully retired at the end of June, 50 years after first arriving at KU as a student, and soon held in her hands a beautiful career capstone—which included thrilling surprises (to Schulte) of a foreword from Chancellor Doug Girod and endorsements from notable Jayhawks of the highest order.

“The Jayhawk has been my companion and my protector during my whole life,” wrote Juan Manuel Santos, c’73, former president of Colombia and winner of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize. “This book is a great reminder of what makes the Jayhawk special!”

And what of this Patrick Devlin, perhaps the person most often commonly identified as the earliest Jayhawk?

Thanks to that first-person account that Schulte uncovered in Watson Library’s stacks, her research identifies an 1848 band of gold prospectors as the first to self-identify—for reasons unknown—as Jayhawkers. And within the archives of the Kansas State Historical Society, she also found an account by John B. Colton, a member of Manly’s expedition, who offers the first, and now familiar, description of a “jayhawk” as a fictional bird of prey that sails along on the hunt for its next meal, until an “audience of jays and other small but jealous and vicious birds sail in and jab him,” and the irritated hawk “slides out of trouble in the lower earth.”

By 1856, however, “Jayhawk” had arrived in Kansas—as a verb—thanks to Devlin. Citing accounts uncovered in her research from the border counties Miami, Linn and Bourbon, Schulte writes that as Devlin returned to Osawatomie one morning with a heavily loaded mule in tow, a neighbor asked what he’d been up to. “Jayhawking,” Devlin said of his foraging and harassing across the Missouri border. Devlin further explained that back in Ireland, a bird called the jayhawk “worried its prey before devouring it.”

The Jayhawk, it is clear from the outset, is about far more than a mascot held so dear by all who love the University far above the golden valley. It is about the history of a state that found its footing in times of the country’s greatest upheavals, and subsequent generations of students, faculty, staff and alumni who dedicated themselves to grand ideals of teaching, learning, research, service and school spirit.

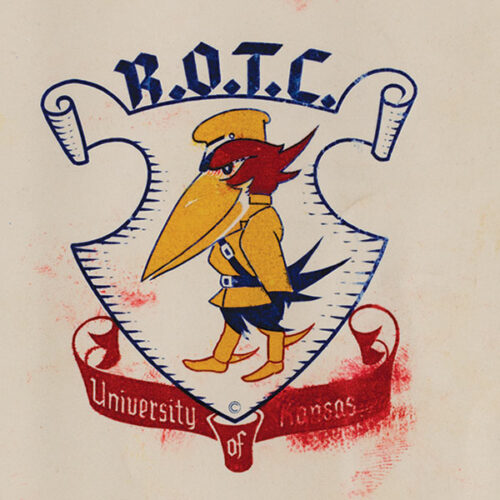

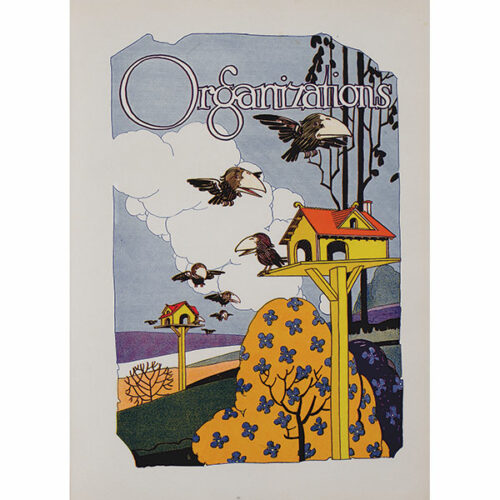

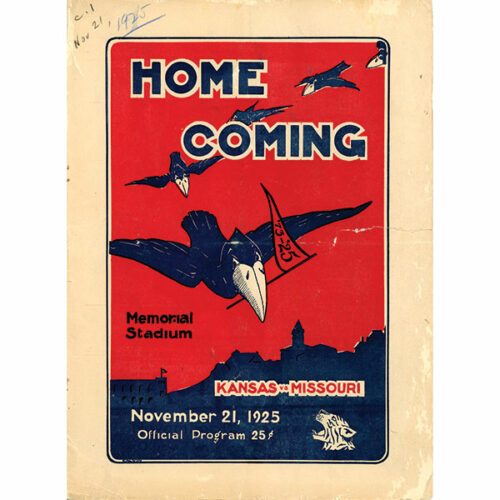

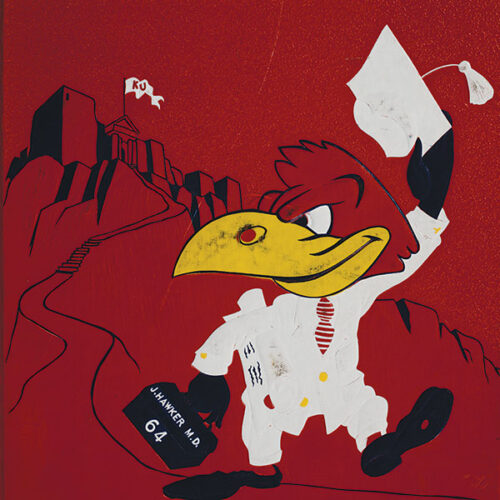

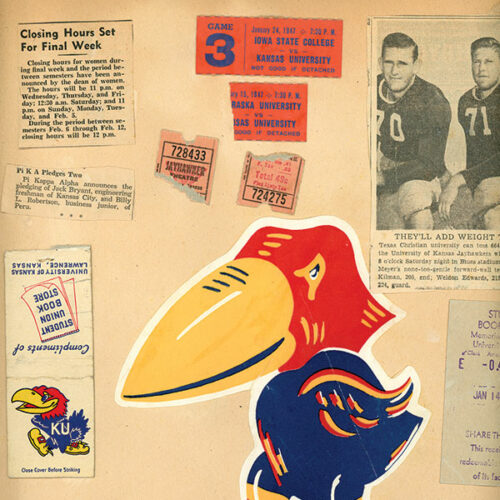

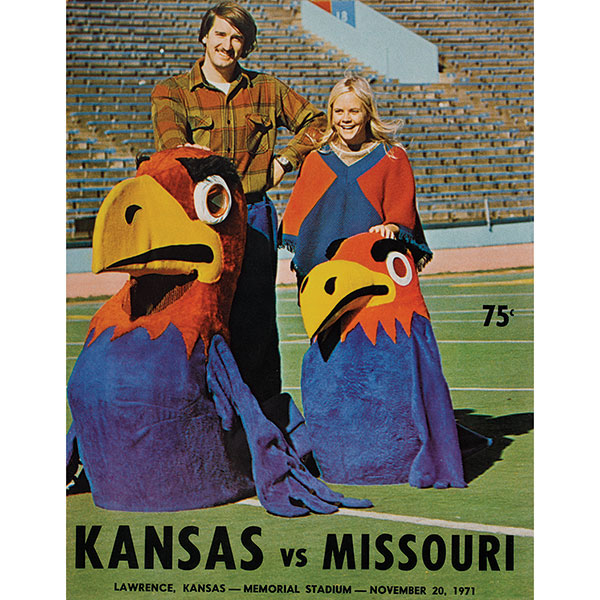

Thanks to Schulte’s gifted narration, the path through her book, through the story of the Jayhawk, can be navigated at the reader’s pleasure—typically, she says, first by flipping through pages to sample the more than 300 images. Most have long been locked away in such treasure chests as student scrapbooks, boxes of ephemera dutifully preserved and cataloged in University Archives, collections of Jayhawker yearbooks, and the Alumni Association’s Graduate Magazine and Kansas Alumni magazine.

Then comes a pause to glance through captions, which ignites an interest in the nearby text, which in turn spurs a reader to turn back a few pages and start putting the unfolding story in order.

“You just go back and back and back and back,” Schulte says, “and then you get to the beginning and it’s like, ‘OK, well, maybe I’ll just sit down and read this.”

See? We promised the homework would be fun.

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Portrait of Rebecca Schulte by Steve Puppe

Archival images by KU Archives and Elizabeth Schulte Esparza

/