First Class

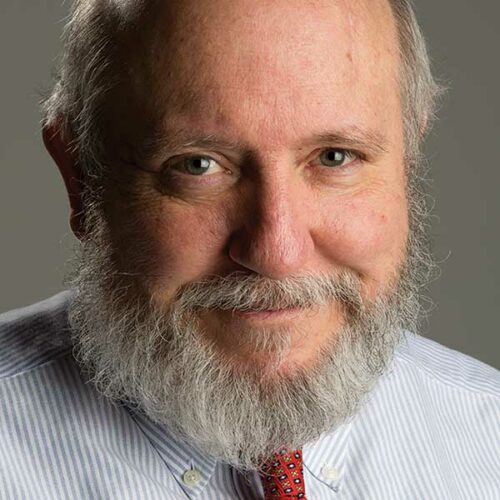

As a young reporter at the Topeka Capital-Journal in the mid-1970s, Doug Anstaett drew on the writing and reporting skills he developed while earning a degree in journalism and mass communications at Kansas State University. But from time to time, Anstaett, now retired from a four-decade career as a reporter, editor and publisher in Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska and South Dakota, was handed a camera.

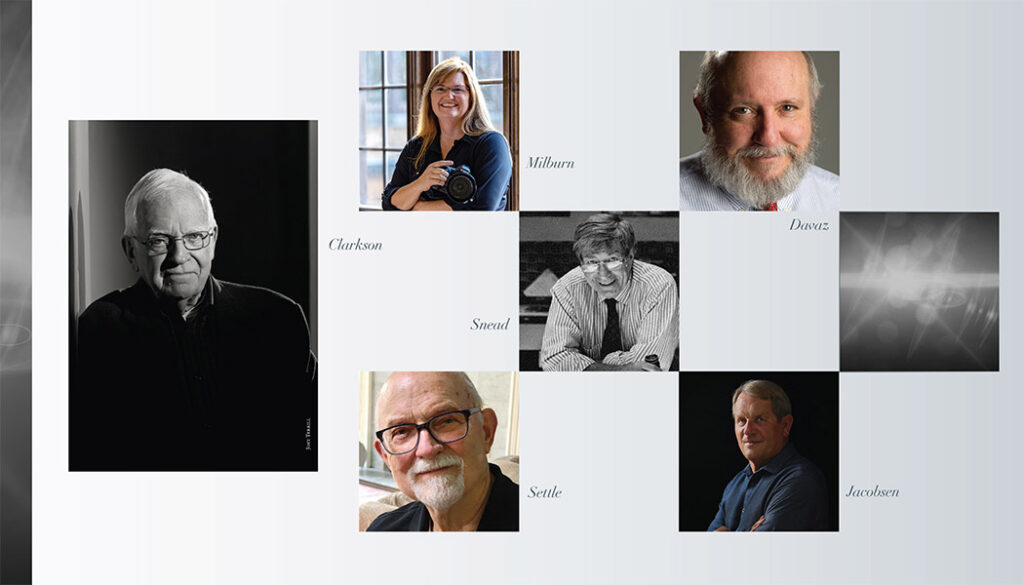

“This was the golden age of photojournalism in Kansas,” Anstaett says, and the Topeka paper’s photo staff was stocked with heavy hitters, a Murderers’ Row of future Hall of Famers, managed by the paper’s highly regarded director of photography, Rich Clarkson, j’55.

But even that deep bench occasionally needed a helping hand.

“Sometimes the photographers would be off taking pictures elsewhere, and the photography department would load a camera with film and give it to us,” Anstaett explains, “with very little coaching beyond ‘push this button.’”

One day, after interviewing—and photographing—the parents of a serviceman who received the Medal of Honor, he returned to the office, turned in his camera and sat down to write.

“As I was writing, Clarkson comes out and says, ‘Anstaett, you have broken every single rule of photography with this. You have terrible backlighting. You posed these people and took the picture straight on. You put the picture of their son on the coffee table in front of them. Every single rule you’ve broken. But it works.’”

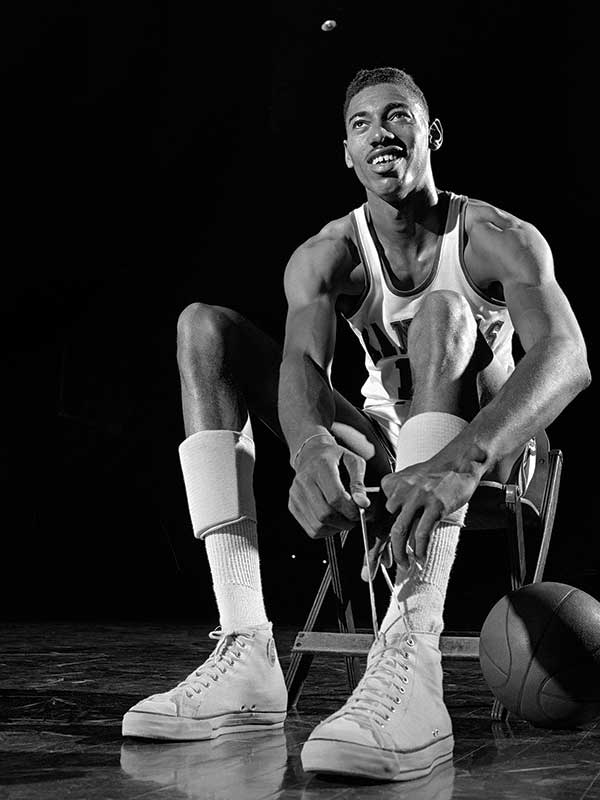

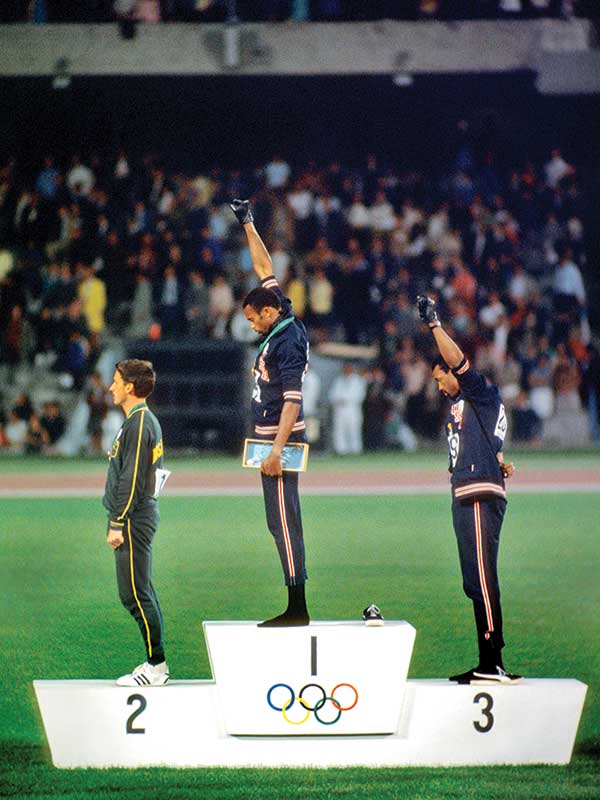

Left: Wilt Chamberlain laces up for the Kansas Jayhawks before his years as an NBA star. | Photo by Rich Clarkson. Right: The silent protest made by Tommie Smithand John Carlos on the 1968 Mexico City Olympic victory stand was a quiet gesture heard round the world. | Photo by Rich Clarkson

“There was a significant portion of journalism history in Kansas that we were missing,” Bradbury says of the decision to establish a hall dedicated to photojournalists. “We have so many award-winning photographers from Kansas that we really need to honor.”

The first class, inducted during a Nov. 19 banquet in Topeka, includes Pulitzer Prize winners, National Geographic Magazine staff members, and an official photographer to two presidents. Many of the 12 inductees have connections to KU and to Clarkson, whom Bradbury calls “the father of photojournalism in Kansas.” Tom Harden, former director of photography at the Louisville Courier-Journal, deemed the 90-year-old Clarkson “the most important voice, mentor and leader that photojournalism has known.”

“We often talk about the ‘coaching tree,’ where a coach like Bill Snyder or Bill Self has created this long list of people they have coached who have gone on to become head coaches themselves,” Anstaett notes. “We found that Rich Clarkson was that person in photography. His coaching tree includes about half of this class. These were people who came to Topeka during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s to work under this icon who, for so many, was a tough, tough coach, but he created some really noted photojournalists through his tutelage.”

Clarkson was director of photography at the Capital-Journal for 25 years, led the photo and art department at the Denver Post as assistant managing editor/graphics, and was National Geographic’s director of photography in the 1980s. For decades he worked as a contract photographer for Sports Illustrated. He photographed six Olympics and 59 NCAA Final Fours, and since 1964 more than 30 Sports Illustrated covers have featured his images. Clarkson’s numerous awards include the National Citation from the William Allen White Foundation, the Fred Ellsworth Medallion from the KU Alumni Association, and the Sprague Award from the National Press Photographers Association. He is now retired from the publishing and photography company he founded in Denver, Clarkson Creative.

The inaugural class also includes Pete Souza, a Pulitzer Prize winner who served as official presidential photographer for Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama; the late photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks, the Fort Scott native renowned for his searing portraits documenting racism, discrimination and poverty in America; Brian Lanker, who won the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography while working for Clarkson at the Capital-Journal; and Jim Richardson, who also worked for Clarkson in Topeka before his 30-year career with National Geographic, where he earned acclaim for capturing global landscapes and the Great Plains while documenting life in rural Kansas.

In addition to Clarkson, five other inductees have KU connections:

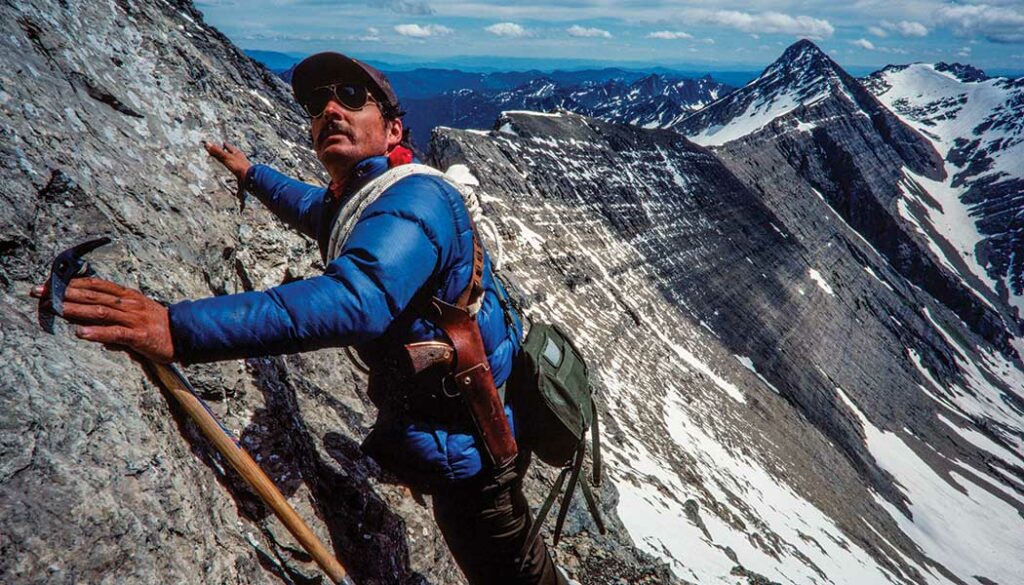

Carl Davaz Jr., ’75, won the intercollegiate photojournalism competition in the 1974 Hearst Journalism Awards Program, the first KU student photographer to claim one of “the Pulitzers of college journalism.” A college internship at the Capital-Journal led to a position on Clarkson’s staff. In 1979 Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian, where his project to visit each of Montana’s 15 federally designated wilderness areas led to a collaboration with two reporters and, eventually, a book. He later worked for three decades as director of graphics at a family-owned newspaper in Eugene, Oregon, the Register-Guard.

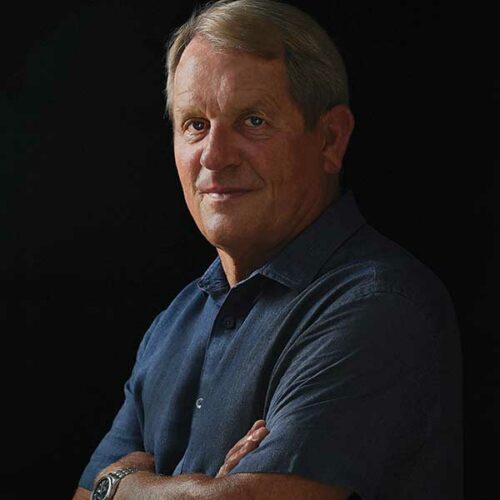

Jeff Jacobsen, former photographer for Kansas Athletics and frequent

Kansas Alumni contributor, started at the Capital-Journal in 1969 as an 18-year-old, sharing photography duties with Clarkson’s talented staff. After a stint at the Arizona Republic, he returned to the Cap-Journal in 1983, rising to managing editor of photography. He began working for Kansas Athletics in 1997, becoming the department’s first full-time photographer. Since retiring in 2020, he has been at work on a long-term project to document the people and events that make sports an integral part of Kansas, traveling to all 105 counties in the state.

Sandra Watts Milburn, j’89, worked for the Hutchinson News as a summer intern in 1988 while studying at the William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communications. A year later she joined the paper full time, rising to photo editor in 1995. Her aerial photograph of the Greensburg tornado was named the 2007 Photo of the Year by The Associated Press. In a farewell column earlier this year, she noted the many changes she worked through in her 32-year-career, including the transition from slide film to color negative film to digital cameras and videography. Since 2019 the sole photojournalist on staff, she was laid off by Gannett in a round of nationwide cuts.

Gary Settle, j’61, learned photography from his father and had already worked behind the camera—on his high school paper and yearbook and as darkroom boy/photographer at the Hutchinson News-Herald—when Rich Clarkson hired him in 1958 as a summer intern at the Capital-Journal. In a long career that included stints at the Wilmington (Delaware) News-Journal, the Chicago Daily News and the Seattle Times, Settle was named photographer of the year twice by the National Press Photographers Association. His beat for the New York Times’ Chicago bureau took him to dozens of states—including to Houston in 1969 for the return of the Apollo 11 astronauts.

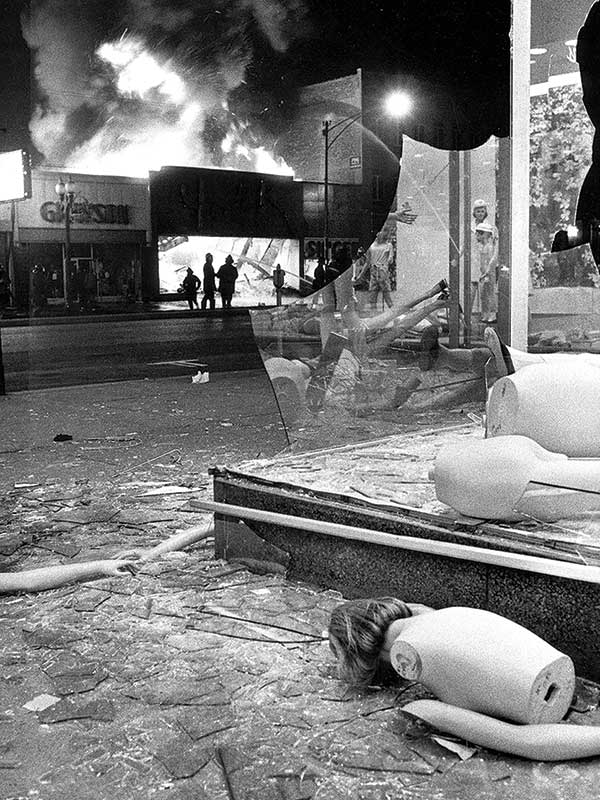

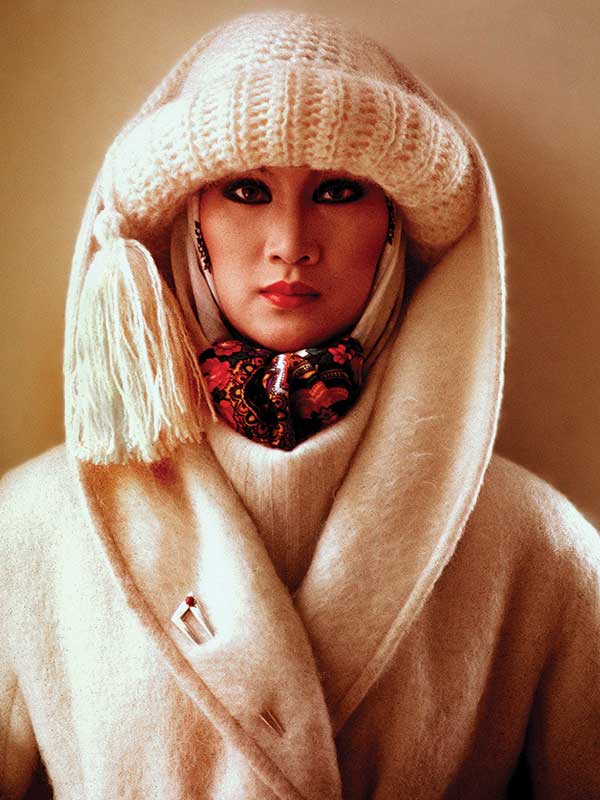

Left: Following Dr. Martin Luther King’s murder in Memphis, in April 1968, undressed mannequins litter a sidewalk on Chicago’s West Madison Street, where more than a hundred businesses on the city’s west side were looted and burned. | Photo by Gary Settle. Right: New York fashion shoot, 1978. | Photo by Bill Snead

Like many who worked for Clarkson, Snead considered his mentor a tough, demanding critic whose high standards proved a firm foundation for a long career in photojournalism.

“My good fortune started when I was hired by the Journal-World’s photo-boss-from-Hell, Rich Clarkson,” wrote Snead, who died in 2016. “‘That’s good enough,’ was not in his vocabulary. His emotional kicks in the [butt] gave me a head start in a trade I care for as much today as I did a hundred years ago.”

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photos courtesy of the photographers and the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame

/