Ode to joy: KU orchestras conductor Creston Herron

Issue 1, 2025

On a brisk night in Swarthout Recital Hall, the 23 musicians of KU’s Prairie Fire Chamber Orchestra appear jazzed, as does their conductor, Creston Herron.

Never mind that it’s Dec. 12, the Thursday before the gauntlet of final exams—or that the students and Herron began the long week by performing twice on Sunday, with the KU Symphony Orchestra, in the School of Music’s 100th edition of holiday Vespers.

Tonight’s concert marks the giddy debut of Prairie Fire, an ensemble that Herron founded this fall to “expand the string orchestra repertoire, focusing on new voices, underrepresented populations and varied composers,” he explains to the Swarthout audience. Two of the night’s selections, in fact, are world premieres of new music, commissioned especially for Prairie Fire.

But the program will begin with an “old gem,” Herron says, as he introduces the “fiery and feisty” first movement of Tchaikovsky’s “Souvenir de Florence.”

“Fasten your seat belts, because from beginning to end, this is true Tchaikovsky at his best,” Herron continues, “with wonderful flurries and excitement, beautiful melodies and dissonances that leave the listener just in awe.”

“Souvenir de Florence” also hints that the night’s performance is prelude to Prairie Fire’s upcoming tour in Italy, the first international trip in the history of KU orchestras. From Jan. 8 through Jan. 15, the students will present concerts in Florence, Rome, Venice and Cremona, birthplace of the violin.

Allegro con spirito, the first movement of “Souvenir,” also describes the lively, effusive Herron, f’08, now in his second year as the School of Music’s director of orchestral activities. Witness his preconcert frenzy: Before his players assemble on stage, Herron warmly welcomes and prepares the youthful guests seated in the first two rows of the audience for the music they are about to hear. They are music students at Gardner-Edgerton High School and Kansas City’s Sumner Academy, Herron’s high school alma mater. He is oh-so-subtly recruiting them to KU by explaining the abundant musical opportunities they could encounter.

He then dashes out of the hall to retrieve the printed programs for the concert, quickly returning to distribute copies, row by row, greeting individual audience members. Eventually, he makes his entrance on stage to introduce Prairie Fire and the night’s repertoire.

“He’s an unstoppable force,” says Margaret Marco, professor of oboe, associate dean for performance activities and a 26-year School of Music faculty member. She credits Herron for rejuvenating the orchestral programs, which in addition to Prairie Fire, include the KU Symphony Orchestra and the KU Philharmonic Orchestra.

Marco first encountered Herron when he was an undergraduate student in her music theory class. “I knew then he was going places,” she recalls. “He was just a sponge—full of curiosity and asking insightful questions. When he applied for graduate school at Rice University, I thought, ‘Yeah, this kid is going for the stars.’ He was just a joy.”

Last fall, for the 100th Vespers, Herron asked Marco to perform an oboe solo with the Symphony. As she entered the Lied Center stage during dress rehearsal, “the change in the atmosphere was palpable,” she says. “The students responded to him with such enthusiasm, and this lush, gorgeous sound was coming out of the string section that I had not heard from the KU Symphony Orchestra for many years. I started crying.”

Melanie Lysaught, Topeka sophomore and a violin performance major, praises Herron’s “amazing ability to draw you in and engage you in the music.” The Prairie Fire ensemble has introduced her to new music and ideas she never encountered during her years of classical music study. “It’s cool to experience these pieces and know that no one has ever played them before,” she says. As a conductor, Herron has helped her play better as a member of an orchestra. “He emphasizes in every rehearsal that it’s so important to listen to one another and play as one breathing ensemble rather than just a bunch of individuals playing at the same time.”

Prairie Fire member Sofia Lefort, a Lawrence sophomore majoring in music and psychology, recalls meeting Herron in fall 2022, as the School of Music was beginning its search for a new director of orchestras. Herron accepted the school’s invitation to lead the KU Symphony as a guest conductor. Lefort was a high school senior who had been invited by a KU faculty member to perform, but when she arrived for the concert, “they had forgotten to put out a chair for me because I wasn’t on the roster,” she recalls. “Professor Herron flagged people down to get me a chair, and then he took a selfie with me.”

She was delighted when Herron accepted KU’s offer to return as a faculty member. “I was really happy when he got the job,” she says. “He has a way of managing massive ensembles while making everyone feel heard and seen. He even asks about our families.”

The memory of his fall 2022 “audition” lingers with Herron, too, because it transported him back to his years as an undergraduate violin performance major. “It brought back so many wonderful memories for me,” he says. “I could see myself then, and I could see what the experiences here afforded me. I can support my family because of the experiences that I had here at KU. And I thought, ‘This is my opportunity to give back and inspire that next generation and hopefully give them the opportunity to pursue their passions and have their own careers.’

“I felt so connected with the students, and they were so responsive. It just felt very organic.”

Herron and his wife, Dawn, and their young children moved to Lawrence in 2023 after 15 years in Houston, where he served as director of fine arts for the Klein Independent School District. He also conducted the Shepherd School of Music Campanile Orchestra at Rice University, where he earned his master’s degree.

In only his second year on the KU faculty, Herron has overseen impressive growth in the three orchestral ensembles, says Marco, who notes that the string sections have doubled in size. The Symphony now includes about 85 players, most of whom are majoring or minoring in music. The 40-member Philharmonic Orchestra comprises students from all majors as well as members of the faculty, staff and community; Herron renamed the group and has challenged the musicians with a more rigorous repertoire.

Marco hails the Philharmonic as a prime example of Herron’s impact. Previous orchestras for non-majors and community members had been hit or miss, she says. “We had a revolving door of conductors, so the consistency and the coherency of the program wasn’t there—unlike the band programs, where directors have stayed for long periods of time. The secondary orchestra was a ship without a rudder, and it needed somebody who’s going to be here and have a commitment.”

One of the Philharmonic’s community members has an especially personal stake in Herron’s success: His mother, Courtney Wells of Kansas City, plays violin, the instrument she inspired her son to take up as a child. Mother and son share not only a passion for the violin but also the same vivacious, gift-of-gab personalities. He fondly describes her as “a hoot.” It takes one to know one.

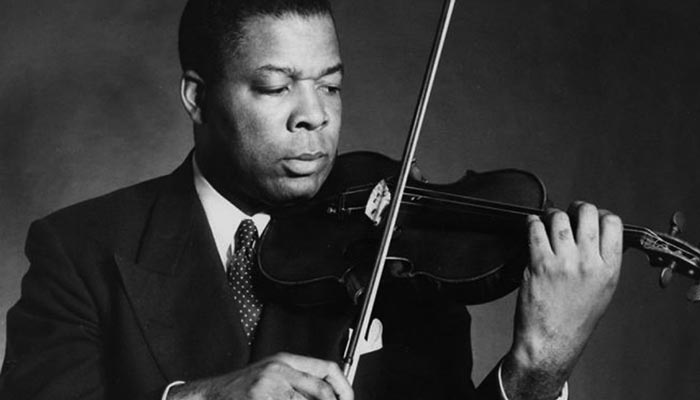

Herron continues a musical tradition that cascades through several generations of his family, including his late great-uncle and fellow Jayhawk, Reginald Buckner, d’61, g’66, who founded the jazz program at the University of Minnesota and gained national attention for his TV series and lectures on jazz. Buckner is the latest graduate to be inducted into the School of Music’s Nicholas L. Gerren Sr. Hall of Achievement.

Although Herron is too young to have truly known his great-uncle, “his name was synonymous with musical excellence,” Herron says. “He was a force in the field of music, and I grew up knowing there was musical excellence that came before me. It set a tone for me, where I know what the bar is; I know what the possibilities are. And so why not reach for those possibilities? I know they’re attainable.”

Herron clearly announced the possibilities for KU’s orchestras before he returned to the Hill. “The minute he signed the contract,” Marco recalls, “he said, ‘We are going to have a string orchestra, and we’re going to have a vibrant orchestra for non-majors and the community to play.’ He’s got so much vision, and those are just two tiny tentacles of his vision.”

Herron clearly states his bigger plan. “In the next five years, the KU orchestral program will be one of the top 20 in the nation. That is our goal,” he says. “We will be seen as the mecca for music education, especially string education, in the Midwest.”

Last summer, he established the first Midwestern Music Educators Retreat, which coincided with KU’s well-known Midwestern Music Camp, for decades a fertile recruiting ground for KU music students, including Herron. The new retreat attracted teachers from six states who met with faculty from KU and across the nation to discuss rehearsal techniques and classroom innovations. The retreat was a “resounding win,” Herron says, and plans for this summer’s retreat are well underway.

Teaching and conducting were not part of Herron’s plan as an undergraduate, but on a whim, he enrolled in an elective course on conducting taught by Professor Paul Tucker, then KU’s director of choral ensembles. When Tucker presciently suggested that Herron might one day trade his bow for a baton, Herron dismissed the thought: “My vision for myself was to go be a performer, playing overseas with professional groups. I thought I would be a concertmaster. Conducting just never really appealed to me.”

Until it did. As a master’s student in violin performance at Rice University in Houston, Herron was an Alice Pratt Brown Scholar in the Shepherd School of Music and a faculty member in the school’s preparatory program for young children. “I realized that I like working with kids, helping them experience their creative side through music and seeing how they light up,” he recalls.

But when he learned that a Houston public charter school was looking to hire an orchestra director, Herron resisted, at first ignoring his professor’s suggestion to apply. Ultimately he relented—and discovered true joy. “The first time I got on the podium, the energy flew through me,” he recalls. “It was overwhelming. I almost cried. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh. I want this.’ I’ll never forget that experience. I was just blown away. That’s when I knew.”

Herron explains that his performance background feeds his role as conductor. “Your study of the score and your interpretation are enhanced,” he says, “because the conductor’s job is really to portray what’s not on the page. What’s the character? What’s the color? What’s the story? That’s my job.”

And when the conductor and musicians truly connect, every gesture speaks volumes, Herron says. “The word itself, ‘conduct,’ means you’re a conduit of energy. It goes through you. It’s not a dictatorship, but it’s a collaboration. We’re making the music together. That’s why I like to be within the sound and see the players’ eyes up, out of the score. I show them what I want, and if it’s clear and concise and decisive, the musicians understand. It’s organic.”

In this new, allegro con spirito era of KU orchestras, all eyes are on Creston Herron and the musicians he inspires.

You may also like: Read about many of the trailblazing Jayhawks honored in the KU School of Music’s Nicholas L. Gerren Sr. Hall of Achievement in A legendary legacy of jazz at KU.

Jennifer Jackson Sanner, j’81, is editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photos by Steve Puppe

Rome photos by Fally Afani, School of Music