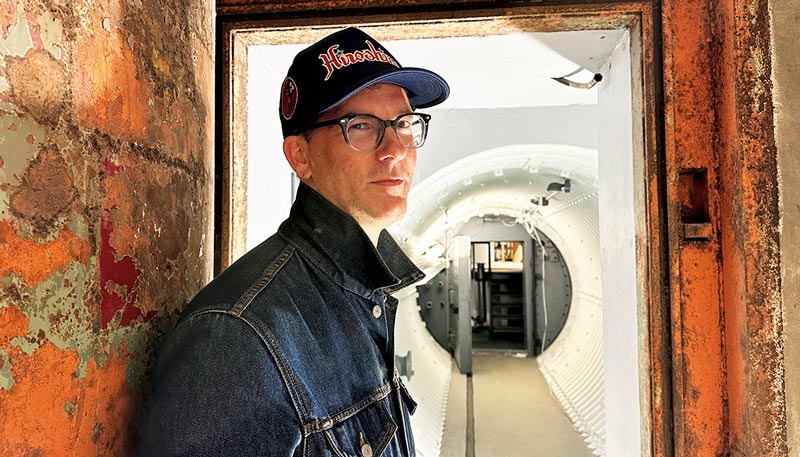

The big reveal: Portrait artist John Boyd Martin’s enduring eye

Issue 2, 2024

John Boyd Martin earned his first commission at age 11, when a friend asked him to sketch a likeness of Notre Dame’s Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback Johnny Lujack. Having already provided his buddy with a pencil drawing of another Heisman winner, Army’s Doc Blanchard, Martin was quick to realize that his talent for creating images of famous people had value.

“I said, ‘Well, I could use a little money for this,’ so he paid me a dollar,” Martin recalls, joking that the forfeiture of his “amateur status” came at such a young age and for such a modest fee.

That was in 1947, and Martin—who grew up across the street from Ottawa University, the Baptist college south of Lawrence where his father, Andrew Martin, served as school president—had already been drawing for years, starting with the preschool art he scribbled in the blank pages of his father’s books. He later created pen-and-ink campus scenes for the university Christmas cards sent out each year by his family. After a KU degree in commercial art led to a productive career in advertising, he came back to portrait work in the 1980s, “a bit of a late bloomer” in his mid-50s. Decades later, at 87, the prolific painter has completed an estimated 900 commissioned portraits of sports figures, medical researchers, business executives, university leaders and U.S. military commanders in formats that have included massive murals, traditional oil and watercolor canvases, books, game programs and even, in a throwback to his first post-college job as a commercial illustrator, Pizza Hut place mats.

A tour of Martin’s work would include stops at Allen Field House, Wagnon Student-Athlete Center, the Chancellor’s Office in Strong Hall, the Adams Alumni Center, the Lied Center, Kansas Memorial Union, and the Phi Gamma Delta and Phi Delta Theta fraternity houses. And those are only the KU campus sites (see “True blue Jayhawk,” below).

Martin, f’59, also has work hanging in the Pentagon, the U.S. Capitol, the Marine Barracks and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. His paintings are a highlight of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, as well as the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame in Wichita. Before the NCAA moved its headquarters to Indianapolis in 1999, the organization’s Overland Park campus was home to Martin’s biggest project, a 92-foot-long mural depicting key figures and great teams from the NCAA’s first century.

Even as a few of his largest, most ambitious installations have been edged out of the public eye because of building renovations and the digital-age emphasis on interactive, screen-based exhibitions, Martin has continued to produce traditional portraiture at a high rate. Commissions completed in the past year include oil paintings of manager Ned Yost for the Kansas City Royals Hall of Fame; Vanessa Beasley, the first female president of Trinity University in San Antonio; and U.S. District Judge Julie Robinson, j’78, l’81, the first African American appointed to the District Court in Kansas. Although Martin decided earlier this year to cut back on his workload, commissions continue to roll in: Over the next few months he will produce portraits of Bo Jackson, Cedric Tallis and John Schuerholz for the Royals Hall of Fame; portray founders Virginia and James Stowers for the Stowers Institute; and complete a panel depicting the 2022 NCAA champion men’s basketball team for a mural at KU Athletics that he began in 1979, when Ted Owens coached the Jayhawks.

“It’s been a great run as far as the amount of work through the years and the people I’ve met,” Martin says. “I’ve just been blessed. I can’t describe it any other way.”

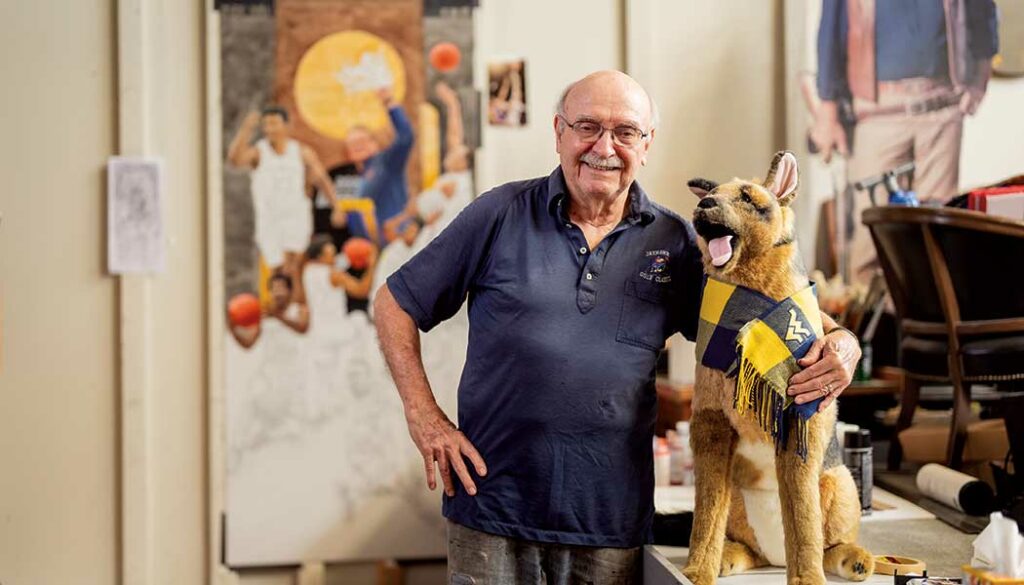

Martin works out of a studio he built onto his Overland Park home, where he lives with his wife, Ruby Sterlin Shade Martin, d’59. The cathedral-ceilinged space is awash in northern light and packed with art supplies and an abundance of curiosities, including a snooker table from the early 1900s, a life-sized German shepherd plushy, and a scale-model replica of Louis Bleriot’s Type XI monoplane (the first airplane to cross the English Channel), complete with Snoopy in the cockpit.

The dog—the German shepherd, not the Peanuts mascot—is an artifact of Martin’s portrait process, and he acquired the toy after earning a portrait commission for John Bilbrey, CEO of The Hershey Co.

“A lot of your CEOs have security dogs for protection,” Martin explains, “and Bilbrey wanted his dog in the painting.” With the help of his wife at the time, Bonnie Martin, who died in 2021, he found the prop online and had it ready when the CEO showed up for the sitting. “I said, ‘You’ve got a friendly visitor in the studio,’ and when he saw the dog he about fainted,” Martin recalls, chuckling at the thought of a captain of industry momentarily taken aback by what would seem to many, at first blush, a laughable prop.

The stuffed pooch was a stand-in, of course, a placeholder for the real dog, which would be painted later. It had a practical purpose. But springing it on Bilbrey the way he did—as a lighthearted icebreaker—was also a calculated move, one of many that Martin undertakes to establish a connection with each person he paints.

Once he secures a commission, he schedules an initial meeting with his subjects, usually on their turf. Setting up that meeting can be difficult, especially with CEOs, Martin notes. “These are executives; they don’t have any time,” he explains. “And the thing you have to keep in mind is that—for a lot of them—having a portrait made wasn’t their idea.”

The face-to-face visit is an essential first step in getting to know the subject and putting them at ease.

“We talk about it over food,” Martin says, “preferably dinner with their spouse.” The social setting allows him to observe the subject’s facial expressions and gestures, to ask important questions about how they want to see themselves presented in the painting and what setting, poses or props might be appropriate. It’s a chance to establish rapport while also getting a glimpse, hopefully, into key elements that bring a portrait to life—what Martin once described in a newspaper profile as a subject’s “inner beauty, their quirks, their history, their hearts.”

“John is one of the few artists who wants to sit down informally and learn a lot more about his subjects,” says Ann Fader, founder and president of Portrait Consultants, who has matched Martin with about 70 clients since she began to represent him in the 1980s. “When he sits down with a subject, he is observing their facial expressions, their delights, at a time when they don’t believe they are being observed. Most people of power and accomplishment have already learned how to fix their face for the camera, but this is John’s way of seeing what they are like when they’re not in front of a camera. And that is a key to his talent. You not only have to know what to do with a brush, but you have to see your subject beyond just his or her facial features.”

Mary Overstreet, an associate at Portraits Inc. in Nashville, Tennessee, represents more than 100 artists. “John Boyd Martin is my favorite,” she says. “I have some artists who might meet with the family, but no one goes as deep as John. I mean, he just is on a different level.”

The sitting, which consists of a two- to three-hour photo study followed by a three- to four-hour painting study, usually takes place the next day. Afterward, Martin returns to his studio to prepare a series of sketches that are sent to the client to select a pose for the final painting. From there, he uses the photographs, painting study and sketches to produce the finished work. Once it’s done, he packs and ships the painting to its destination and travels there himself to present it for the client’s final approval. Any touch-ups or adjustments are accomplished with the input of the subject (or, in the case of a posthumous portrait, the person or organization who commissioned the piece).

The unveiling is the moment of truth, and Martin manages it carefully.

“You don’t unfold it in front of ’em like a package,” he says of the reveal. “You have it all set up, lit the way you want it. I always try to get into a conference room somewhere, so when they come in and see it for the first time, it’s ‘Ta-da!’ It’s the old adage that you don’t have a second chance to make a first impression. You’ve got to wow ’em, because that’s the moment: Either it’s there or it’s not.”

“It”—that certain something that makes a portrait work—is hard to define. It involves a surface likeness, of course, but something deeper, too.

“For the delivery of a portrait, you do have to have a good likeness,” Overstreet says. “I mean, it’s got to look like the subject, clearly. But to be a superior portrait artist, you have to be able to reflect the spirit of the subject, the personality, the twinkle in their eyes, the little crooked smile or whatever it is that people who are close to the subject will see and say, ‘That’s our guy. That’s our guy.’”

Baseball legends Joe DiMaggio, Buck O’Neil, Willie Mays, Ted Williams, Hank Aaron and Stan Musial. Kansas City sports icons George Brett, Lamar Hunt and Len Dawson. Golfing greats Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino and Tom Watson. Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Richard Myers, Secretary of the Army Louis Caldera and Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman. Texas billionaire and U.S. presidential aspirant Ross Perot and more than a dozen of his business associates. They and many others have posed for Martin, usually after getting the painter’s full hands-on treatment—sometimes literally.

For a portrait of Arnold Palmer that hangs now at the USGA headquarters, Martin visited the Hall of Famer at his course in Orlando, Florida.

“I said, ‘Arnie, I have this idea: You’re looking down the fairway and you’re pulling a club out of the bag,’” Martin recalls. “We’re out on the tee, and he gets in position, and I said, ‘No, that’s not quite right.’ I went up behind him and showed him what I wanted.”

The mischievous smile creasing Martin’s face breaks into a delighted cackle.

“If you could have taken a picture of that, it looked like I was giving him a lesson! I mean, are you kidding?”

Producing a portrait that reveals the true character of the subject is a collaboration between painter and poser.

“Being a portrait artist is different,” Martin says. “A portrait artist, first of all, you have to love to be around people. You can’t be one of these my-way-or-the-highway types and do your own thing. You’re actually delivering a painting that has to be approved by who you’re painting, so you have to work in concert with them.”

Ann Fader says Martin is definitely not dictatorial, but he does have a knack for getting more out of a subject than they expect. She recalls one meeting in which the painter was promised only 45 minutes with a busy executive who did not want to sit for a portrait. “Well, they wound up visiting for almost three hours,” she says. “He’s extremely professional, but it comes so naturally to him to want to know anyone who’s in front of him. He wants them ultimately to be proud of this portrait. It is their visual legacy and probably the only part of their legacy that future generations are going to see, and so he excites them with that. And then there’s his natural warmth. One subject was pretty nervous at the beginning, but she said as soon as John walked in, it was like putting on an old shoe. It was just so comfortable.”

The collaboration continues right up through delivery of the portrait. Sometimes there are minor changes—touch-ups, tweaks—to get a painting just the way the client wants it. The approval process is the last leg in a monthslong journey from conception to completion, and sometimes that final step is a real doozy.

Around 2000, Martin completed a posthumous portrait of a doctor for a hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina. The schedule was tight: He planned to show the painting to the subject’s family on a Saturday, and the formal unveiling by the hospital would take place the next day before an audience of nearly 200 medical professionals from across the country. He shipped the painting, as always, in a specially constructed wooden crate and received an email confirming its arrival. But when Martin got to the venue on Saturday, the painting was nowhere to be found. It was finally located in Louisville, Kentucky, and the shipper promised to get it to Raleigh by the next morning.

“The next day we drive to the airport, locate the crate in cargo, and it had been lacerated,” Martin recalls. “A forklift went right through the box and through the painting. Here we are, it’s noon, the event is at 2, and we’ve got a painting with a 10-inch laceration.”

Martin patched the canvas with packing tape, touched up the image and raced to the event, arriving 15 minutes before the scheduled start. Cars were already pouring into the lot, so he parked in a far corner and had the family come out to the van. “People are going into the building and here we are with the family looking at the painting in the parking lot for approval,” he says. “But they understood.”

After the ceremony, where Martin spoke briefly about the mishap, it was decided that salvaging the painting would not be possible. He’d have to redo it.

“There isn’t anything more difficult than redoing a painting that’s already been approved,” Martin says. “That was a tough one, but I got it done.”

Martin may not be able to put into words that certain something, the “it” factor, that makes a portrait work. But he knows it when he sees it.

Or, more precisely, when others see it.

After completing a painting of Deane Malott commissioned by the former chancellor’s son, Bob Malott, c’48, Martin won a second commission to provide a posthumous portrait of Eleanor Malott for the dedication of the Malott Room in the Kansas Memorial Union.

Martin recalls Bob Malott as a tough boss and an intimidating presence. “He was a big, aggressive guy, demanding, a real perfectionist.”

At the Spencer Research Library, Martin found a “wonderful picture” of Mrs. Malott—remembered for her extensive efforts to beautify Mount Oread with flowers and trees—next to a blooming spirea. Working from family photos, he was able to establish important details—hair and eye color, skin tone—missing from the black-and-white image. “That whole painting just fell into place wonderfully,” he says. “But Bob hadn’t seen it yet.”

So, on the day of the dedication, it was with no small measure of trepidation that Martin took Malott in for the big reveal.

“We went into the room and unveiled the painting,” Martin recalls. “And big Bob Malott walks up to that painting, and a tear comes to his eye and he says, ‘That’s my mom.’”

Reactions like that, Martin says, give him the feeling that “I’ve captured what I set out to do.

“That’s my goal. That’s priceless.”

True blue Jayhawk

At KU, John Boyd Martin has painted five chancellors: official portraits of Gene Budig, Del Shankel, Robert Hemenway and Bernadette Gray-Little, which hang in Strong Hall, and a painting of Chancellor Deane Malott, c1921, that was completed for Beta Theta Pi fraternity. His portrait of Dean Smith, c’53, hangs in the Phi Gamma Delta house, as do Martin paintings of Stewart Horejsi, b’59; Stephen Bunten, b’60; and William Morgan, c1885, who founded the fraternity’s KU chapter. Martin painted the portraits of Ernst Lied, ’27, and Christina Hixson at the Lied Center of Kansas; the likeness of James Naismith on the second floor of Allen Field House; and the murals depicting Jayhawk Olympians and All-Americans that enlivened the All-American Room in the original Adams Alumni Center. Several panels of that mural were incorporated in the recent renovation of the center—including those depicting KU’s basketball and football All-Americans—and the others are in storage as the Association looks to find a new home for the works.

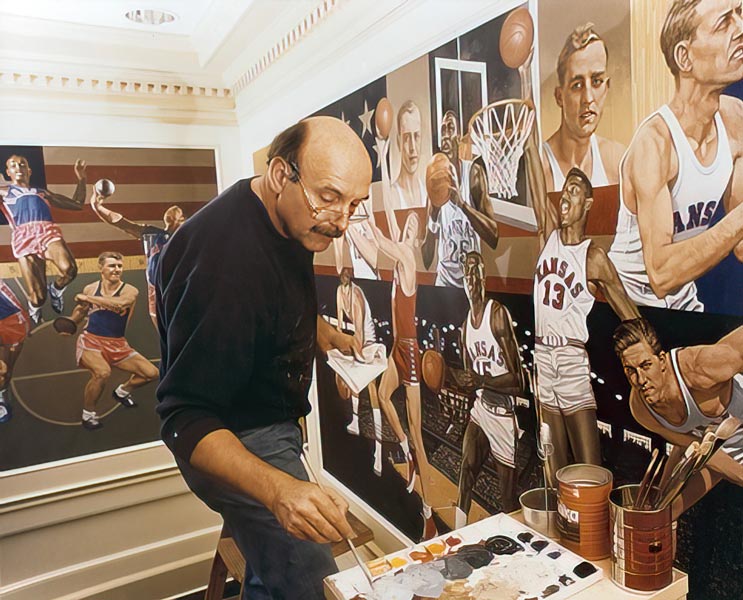

Perhaps Martin’s longest-running project at KU—or anywhere, for that matter—is the mural that stands in a long hallway leading to the men’s basketball offices. Begun during the Ted Owens era, the mural forms a technicolored timeline of Jayhawk basketball, starting with images of James Naismith and Phog Allen, and ending with the on-court celebration of coach Bill Self and the 2008 NCAA championship team. In between are depictions of KU’s Final Four and championship teams, national players of the year, Big 12 conference streaks, and other key moments in the program’s storied history—all updated over the years by Martin as needed. His panel depicting the 2022 championship team, now underway, will be added soon.

“It’s great for recruits to see,” says Chris Theisen, assistant athletics director for communications, “because it’s really an embodiment of the rich history of Kansas basketball. And John’s contribution just adds to it.”

“His face just lights up when he talks about the mural,” Theisen adds. “You can see his pride in KU and his passion. It’s clearly a labor of love.”

Martin was able to meet with Owens when the former coach returned for the 125 Years of KU Basketball reunion in January 2023.

“I think it was meaningful for him to see how it has been carried out and carried on since he originated the idea in 1979,” Martin says. “And it meant a lot to me to hear that from him, and to see him again and show him how the mural has grown over the years.”

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photos by Steve Puppe

All-American Room photo courtesy of John Boyd Martin

Owens and Martin photo by Ruby Sterlin Shade Martin

/