Ripple effect: KU’s Self Graduate Fellowship

Issue 2, 2024

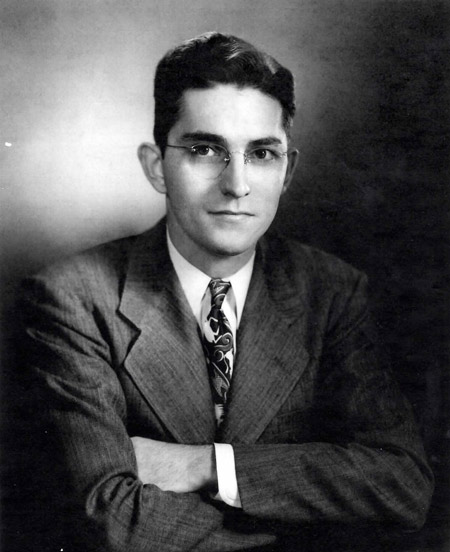

The world was a much different place in 1989, when Madison “Al” Self, e’43, and Lila Reetz Self, ’43, donated $1 million to KU to create the Madison and Lila Self Graduate Fellowship. Yet the couple’s far-reaching vision—that their gift not only would fund exceptional PhD students’ education but also would position promising scholars to become leaders and change-makers—has proved an enduring, successful formula. KU’s Self Graduate Fellows, now an alumni community of more than 200 and counting, have indeed gone on to make vital contributions in addressing some of modern society’s most vexing challenges.

Doctoral students in 22 academic disciplines in STEM, business and economics are eligible for the four-year, highly competitive award that now supports 10 to 15 new graduate students each academic year. Stefani Buchwitz, c’06, g’08, EdD’16, director of the fellowship, says its financial component—which exceeds $200,000, the largest financial package available for any KU graduate student—is only part of its appeal.

“A lot of fellowships throughout the country offer financial support, but very few also include a robust professional development program,” Buchwitz says. “Madison and Lila knew that having a PhD would get you a job, but the development program that they designed as part of the fellowship helps make these students leaders in their field. It’s a distinguishing feature, and it’s incredible that they thought of this 35 years ago and it’s still extremely relevant.”

Madison and Lila met on the Hill—Madison was from Ozawkie, Lila from Eudora—and wed in September 1943. Madison, a chemical engineer, in 1947 co-founded Bee Chemical Co. in Chicago. In his 37 years as CEO, the company, which produced polymer coatings for use on plastics, grew from a staff of three into an international enterprise, with operations in Japan, England and Canada, and clients that included major automakers. After selling Bee Chemical Co. in 1985, Madison founded Allen Financial, a private investment firm, and in 1989 co-founded Tioga International, a supplier of industrial sealants. Despite his immense success, however, Madison, known to those close to him as Al, came to recognize gaps in his skill set.

“Al had a strong professional education, but he knew he would have benefited from leadership training and exposure to other fields to prepare himself for all the decisions he’d later make running a multimillion-dollar company,” says Dale Seuferling, j’77, who, in his role as director of major gifts at KU Endowment in the 1980s, worked closely with the Selfs. “Al hoped that through the fellowship, he could expose students to experience and knowledge outside their own disciplines as a means to better prepare them for the future. He and Lila wanted to make a difference not only in the individual student’s life, but they hoped that student would make a difference for the broader society.

“The Selfs were a very powerful example of a donor reflecting on their own life experiences, what they’ve learned from that, and how they can translate that into the impact of their philanthropy.”

The fellowship’s professional development program comprises an exclusive, customized curriculum that includes oral and written communication, leadership, management, innovation and public policy. The supplemental education aims to expand fellows’ career horizons and fuel their growth into well-rounded, effective professionals.

The value of the development program lies in both the training and in the unique community that arises when top students from a variety of specialties convene.

“When you’re a PhD student, you can hyperfocus on your specific field and not look up and out,” Buchwitz says. “The professional development program gives these highly intelligent, highly motivated PhD students a built-in interdisciplinary network, and that’s where innovation can really thrive. Conversations among PhD students in mechanical engineering, physics, neuroscience, business—those aren’t conversations that exist at KU organically. Bringing these students together in a room is intentional, and that was Madison and Lila’s idea.”

The Selfs (no relation to the basketball coach) continued to fund and refine the fellowship in the years after its launch, and they went on to expand their giving, creating the Self Engineering Leadership Fellows Program, which benefits undergraduate students in the School of Engineering, and a professorship in the School of Pharmacy that honors the late Howard Mossberg, who served as the school’s dean for 25 years and directed the Self Graduate Fellowship from 1991 to 2003. Madison Self received the Alumni Association’s Distinguished Service Citation in 1997, and the School of Engineering honored him with its Distinguished Engineering Service Award in 2000. Self Hall, the Daisy Hill residence hall that opened in 2015, honors the couple.

Both Madison and Lila died in 2013. A $58 million estate gift the following year sustained their existing initiatives and established the Self Memorial Scholarship, which supports outstanding seniors who choose to stay at KU for master’s or doctoral degrees. All told, the Selfs donated $106 million to KU, placing them among the most generous private donors in University history.

“Certainly the size of their gift is historic,” says Seuferling, who led KU Endowment as president from 2002 to 2022. “But what I think is of equal value is the focus on maximizing student potential. The largest portion of their giving, which is focused on graduate studies, is very rare. The undergraduate experience resonates with all college graduates, but it’s more difficult to engage donors in graduate support. It’s really unique, and it’s a difference-maker for KU to have that kind of support for graduate studies.”

Self Graduate Fellows are nominated by their academic departments and chosen by the fellowship’s board of trustees. They are selected for their achievements, lofty goals, leadership potential and passion for lifelong learning. They are employed as graduate research assistants and receive funds to pursue additional professional development.

Jennifer Roberts, managing trustee of the program and senior vice provost for academic affairs and graduate studies, says Self Graduate Fellows create a ripple effect that strengthens KU. “They elevate the level of inquiry, the work ethic and the innovation within their laboratories and departments, so there is a value-add that goes beyond just the fellows themselves,” Roberts says. “Having these students be part of the fabric of the student body enhances the educational experience in a way that sets KU apart.”

Below, Kansas Alumni spotlights a handful of current fellows and alumni of the program who are applying their expertise to critical challenges.

“These are extraordinary students who are being trained at our University,” Roberts says, “and they will go on to make great discoveries and contribute to our society in ways we can’t even imagine yet. We can all be proud of that as part of KU.”

Mary Krause, PhD’11

Amid the upheaval and uncertainty of 2020, Mary Krause was among the scientists who swiftly shifted focus to fast-track a treatment for the COVID-19 virus. Although the antibodies she and her colleagues at the pharmaceutical company Bristol Myers Squibb worked on never came to market, for Krause, the experience still yielded meaningful returns.

“Overcoming some pretty significant stability challenges with the product to get it into clinical trials was probably my proudest moment,” says Krause, who is based at Bristol Myers Squibb’s facility in New Brunswick, New Jersey. “One lesson we learned is that there are always opportunities for acceleration. Being forced to think outside the box to make things happen faster taught us some important skills that we can now apply to get our other drugs to clinical trials faster and hopefully on the market sooner.”

Krause’s path into drug product development was paved by the Self Graduate Fellowship. The Springfield, Missouri, native had always thought she’d apply her lifelong fascination with the natural world—“I was the kid out on the playground picking up rocks,” she laughs—to teaching. She arrived at KU in 2005 after earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in chemistry from Missouri State University, and through the fellowship discovered a compelling new course. “I was going to be a professor all along, but there were other pharmaceutical chemists in the Self fellowship, and seeing their passion helped me identify a different path,” Krause says.

Krause has been at Bristol Myers Squibb for nearly 10 years, currently as director of formulation development in sterile drug product development. She and her team of 10 work primarily on injectable drugs for cancer and autoimmune diseases. “For me, that very tangible piece of taking the active ingredient and going from a molecule to a medicine is the piece that I love,” Krause says. “When a drug product, with different formulation components to ensure it’s stable for its entire shelf life, is actually in a vial or injection device that a patient can touch, it’s incredibly rewarding.”

Her career also satisfies her yearning to teach. “At BMS, we have the opportunity to dig into science, and I get the joy of mentoring and coaching people, which is what I always loved about academia,” says Krause, who leads the STEM group in the company’s global Network of Women. “Getting to help people grow and learn, but getting to do it in a place where we’re also working on very applied science to improve patients’ lives—it’s the best of both worlds.”

And Krause is thrilled to add more of the flock to her team: She hired two fellow Jayhawks earlier this year. “One of the really cool things about being a Jayhawk in the pharmaceutical industry is that there are a lot of us,” she says.

Along with leadership skills, Krause cites the emphasis on communication as a standout part of the Self fellowship. “One gap we often have as scientists is being able to communicate our thoughts in a very clear way, and sometimes people can be afraid of what they don’t understand,” she says. “Having a community of leaders who have that fundamental knowledge and ability to solve a problem that they’re getting from their primary PhD program, combined with the skills that they’re learning from the fellowship about how to communicate and translate that information in a cohesive and clear way—it really can benefit the overall community. People are then learning how scientists can impact their lives.”

David Ménager, e’15, g’19, PhD’22

The robots and computers in Saturday morning TV shows intrigued young David Ménager. “Those shows captured my imagination and ignited a curiosity about what it means for a computer to ‘think’ and if that was really possible,” he says. “As a kid, those questions and the unknown of it all were very interesting to me.”

Now, as an AI scientist at Parallax Advanced Research, Ménager is at the forefront of exploring those grand possibilities as he works to develop higher-functioning, more autonomous AI systems for complex, real-world situations. His niche, cognitive artificial intelligence, focuses on creating AI systems that can reproduce the full range of human intelligent behavior.

“My specific area of expertise comprises theories of event memory, incremental concept formation and cognitive architecture,” Ménager says. “What distinguishes cognitive systems from other areas of AI is that we focus on high-level cognition and we take a systems perspective, thinking about how different cognitive abilities fit together within one implemented system while embracing constraints, such as computing resources and time.”

Medical triage is one such time-sensitive, high-stakes context to which Ménager and Parallax are applying AI to improve decision-making. “In triage, AI systems can leverage my work on event memory to think about what happened in the past, what its experiences were like, and reason from the basis of similar cases to make predictions for the patient,” says Ménager, adding that much of Parallax’s work ties to national security.

Ménager, who grew up in Topeka, came to KU to study computer science in the School of Engineering. As an undergraduate, he was selected as a Self Engineering Leadership Fellow and worked as a research assistant in the lab of Dongkyu Choi, a former assistant professor of aerospace engineering. Ménager went on to earn his master’s and PhD in computer science, exploring cognitive AI systems with Choi and Arvin Agah, professor of electrical engineering and computer science, as his co-advisers.

For Ménager, who now lives in Fort Worth, Texas, perhaps the biggest benefit of the Self Graduate Fellowship was the freedom it afforded him to immerse himself in research. “It allowed me to set the foundation for all the things I’ve done in my career to date,” he says. “I’m getting to make new discoveries in my field and finding new applications for my contributions, getting to work with interesting folks, and it’s all because I had that opportunity to focus on research during my PhD program, and that was because of the Self fellowship funding.”

He leans often on the communication skills he sharpened through the fellowship when writing his research proposals, and he reflects with gratitude on the generosity of the Selfs, which propelled him at each stage of his academic journey. “I feel really blessed and fortunate to have had their support during my undergraduate and graduate careers,” Ménager says. “It has been an incredible gift.”

Rena Stair, c’19

Rena Stair can trace her deep scientific curiosity back to her childhood in Chanute, when she frequently pondered why she and her identical twin sister, Shelby, had slowly changed from an indistinguishable pair into distinct individuals. “All throughout growing up, I was interested in genetics and trying to understand how we were becoming so different and what made us the way we were,” Stair recalls.

Today, the doctoral student in neuroscience applies her quest for answers to a complex human affliction: chronic pain. She will complete her PhD this summer and, thanks to a unique arrangement, since March has also worked in her new role as a scientist at the pharmacology startup Doloromics in Menlo Park, California. Stair aims to develop more precise treatments for pain that would provide targeted relief without side effects and leave the body’s “informative” pain sensations intact.

“So many people’s quality of life is diminished because of chronic pain,” Stair says. “My main goal is to design better therapeutics that can alleviate that burden.”

A first-generation college student, Stair flourished in KU’s inquiry-inviting environment while earning her bachelor’s degree in biology. “In classes, the lecturers would let me ask all sorts of questions and really let me dive in,” Stair says. “I found my time at KU very inspiring for just becoming a scientist.” As an undergraduate, she completed two summer internships at a gene therapy startup in North Carolina that had recently been acquired by Pfizer, and post-graduation worked at Pfizer’s St. Louis site for six months as she prepared for graduate school.

Although another university offered a PhD program that aligned perfectly with Stair’s interest in genetics, “I chose KU because there was a chance I might get this fellowship,” she says. “I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to get that fellowship, and I’m going to do good work.’”

During the first year of her PhD studies, Stair rotated through labs at KU Medical Center, the last of which was Kyle Baumbauer’s. “He had so much energy,” Stair says of Baumbauer, assistant professor of cell biology & physiology and anesthesiology. “And he had this inherent interest in getting all the data he could so we could find out how things work. It was exactly what I wanted in a mentor.” She joined Baumbauer’s lab, where her passion for neuroscience and researching pain took root.

Stair credits the Self fellowship with helping her land her job at Doloromics. While attending a conference in April 2023, she learned the company’s co-founder would be at a Q&A session and resolved to introduce herself. “I was primed to be a little more outgoing than I would have been,” Stair says. “I wouldn’t have approached her if the fellowship didn’t teach me how. And that’s what got the ball rolling.”

The camaraderie has been another highlight for Stair: “To have this cohort of people supporting you, being a witness to your success and also to your failure and continuing to provide reinforcement and motivation—it’s just an incredible bond that you wouldn’t have otherwise. It increases everyone’s likelihood for success.”

Curiosity remains a cornerstone for Stair when she contemplates her future. “My mission is to try to help people in their daily lives, and also to continue being scientifically curious,” she says. “I hope to keep finding opportunities that help me fulfill those missions. There’s probably going to be an opportunity—something that I’m suited for—that I don’t even know is out there yet.”

Grant Downes

While working toward his engineering merit badge in Boy Scouts in elementary school, Grant Downes learned about the relatively new field of bioengineering. “It included all the subjects I was interested in from class, all in one core discipline, and with an application toward human health,” Downes remembers. “It seemed like an opportunity to develop something that would have the potential to impact millions of people—anything from making medical devices to engineering drug compounds.”

Downes’ interest never wavered, and this fall he’ll complete his doctorate in bioengineering. Through his work with his research advisers—Cory Berkland, a former professor of both engineering and pharmacy, and Laird Forrest, professor of pharmaceutical chemistry—Downes has also discovered a complementary calling: entrepreneurship.

“One of the reasons I decided to join Dr. Berkland’s lab was because he has an entrepreneurial mindset in terms of translating academic research ideas and discoveries and trying to commercialize them, to get them from point A to point Z, which is to the person who needs it,” says Downes, whose graduate research has focused on immunotherapy development for Type 1 diabetes, a disease that has affected his family. “That was something that was new to me, and I realized I wanted to pursue a career that combines the technical aspect of scientific research with the entrepreneurial spirit.”

Downes grew up in Kansas City and earned his bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering from Wichita State University, where he competed in track and field. While at a conference to present his undergraduate research, he met Self fellow Bailey Banach, PhD’22, and their conversation put KU’s bioengineering doctoral program on his radar.

Alongside his PhD work, Downes has cultivated his entrepreneurial acumen, taking classes in the School of Business, interning at the University Venture Fund Crossroads in Kansas City and participating in the Entrepreneurship for Biomedicine training program at Washington University in St. Louis. The Self fellowship community has provided additional knowledge. “Getting perspectives from all different disciplines is important for not only diversity of thought,” Downes says, “but for keeping your brain sharp and continuing to think about things in different lights.”

After graduation, Downes, who competed on KU’s track and field team for two years, aspires to work with entrepreneurs, ideally as a venture analyst at a biotech investment firm or as a consultant for small companies. Longer term, he’d like to play a part in increasing career opportunities for biomedical engineers in the Midwest.

The ability to convey his scientific research in a way that’s accessible to a broad audience is a skill Downes has been thankful to hone through the fellowship. “You can do all this data crunching and all these experiments,” he says, “but at the end of the day, you need to be able to talk about it and communicate it in an effective way. That’s something the fellowship has allowed me to grow in: making sure my ideas are coming across as I intend, without misunderstanding.”

With funds from the fellowship, Downes traveled to Paris in May 2023 to present his research at the Immunology of Diabetes Society Congress, where he received fresh feedback on his work and connected with peers from around the world. “You can’t really put a price on the opportunity this fellowship provides from a professional development standpoint,” Downes says. “I wouldn’t trade the fellowship for anything. It’s been one of the most transformative experiences of my life.”

Megan Hirt, c’08, j’08, is assistant editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Madison and Lila Self photo courtesy of KU Endowment

Self Graduate Fellows group, Madison Self and David Ménager photos courtesy of the Self Graduate Fellowship

Jennifer Roberts and Stefani Buchwitz, Mary Krause, Rena Stair and Grant Downes photos by Steve Puppe

/