Modernism, here and now: KU builds on modern art prestige

Issue 3, 2023

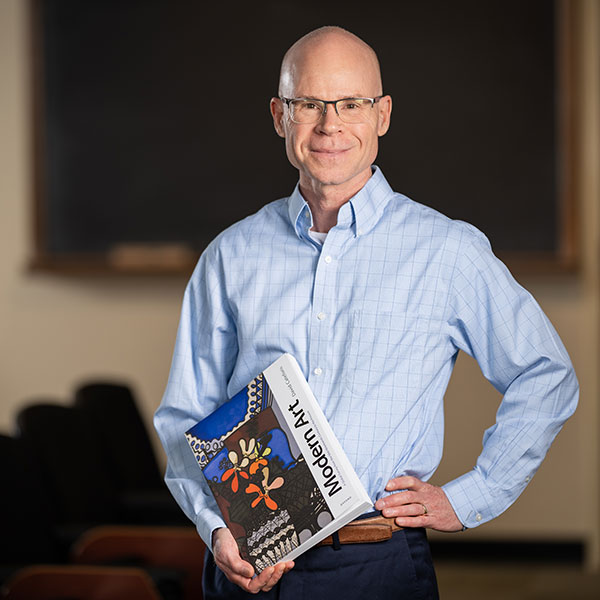

Although they are called “Senior Sessions,” the Spencer Museum of Art’s regularly scheduled weekday gallery lectures are open to one and all. So it was that on April 13, David Cateforis, professor and chair of KU’s Kress Foundation Department of Art History, found himself before a sizable gathering in the museum’s fourth-floor Michaelis Gallery.

Cateforis opened his lecture—“Three American Modernists: Elaine de Kooning, Louise Nevelson, Elizabeth Murray”—standing near one of the museum’s most important and exciting recent acquisitions, a 1959 de Kooning painting titled Arena.

“It’s a painting that seems restless, that seems to be very fresh, with a quality of immediacy, the quality of spontaneity,” Cateforis began, before sharing a brief synopsis of abstract expressionism’s 1940s emergence in New York City.

Trim, sharply dressed and precise in his speech, Cateforis suggested to his audience that perhaps Arena is not so much about a bull in the throes of a doomed showdown as it is about the artist’s confident brushstrokes and dynamic use of motion and color. Even the title, Cateforis suggested, might refer not to the bullring but instead to the canvas, “a setting for action, or even struggle, between the artist and her materials. … The artist doesn’t know the outcome of that process. It’s risky. It could go wrong. But it’s exhilarating.”

As he turned toward the next topics of discussion—Murray’s massive Chaotic Lip, a 1986 piece acquired by the Spencer in 1987, followed by Nevelson’s 1971 aluminum sculpture Seventh Decade Garden IX-X, recently refurbished and moved indoors after decades of sentry duty on the Spencer’s front walk—Cateforis held his gaze on Arena for an extended beat.

“This,” he said, “is such a treasure.”

Although the hourlong gallery talk was a thrilling and seemingly complete overview of what museum patrons might find in three prominent works of modern art, Cateforis curiously omitted even a passing mention of another important development in the field of modern art at KU: the arrival of his massive yet elegant textbook Modern Art: A Global Survey From the Mid-Nineteenth Century to the Present, published this spring by Oxford University Press.

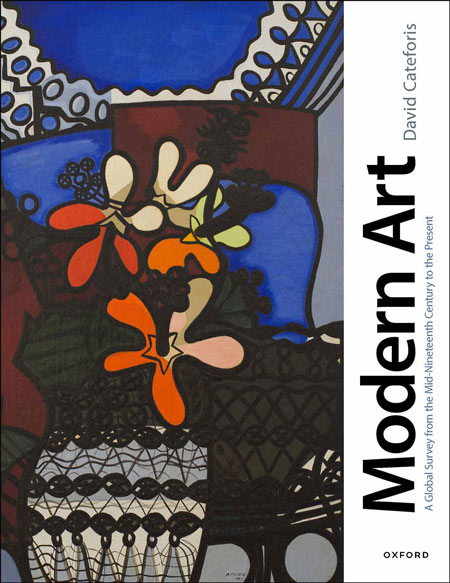

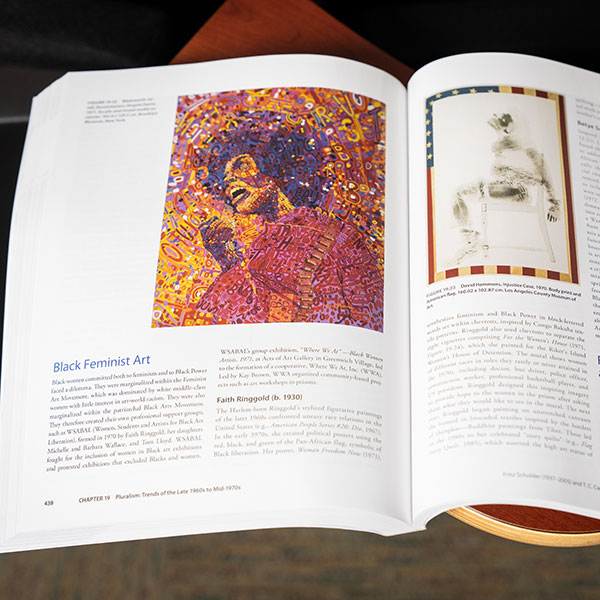

Professor Cateforis chose for the cover of his book a splendid image up to the task: Marpacifico, by the Cuban painter Amelia Peláez, an alumna of Havana’s Academia de San Alejandro who abandoned her country’s prevailing academic art while studying in Paris from 1927 to 1934. The first work of art encountered in Modern Art signals a fresh, inclusive and welcome approach to a subject too often dominated by towering European men whose work, after initially horrifying critics and public alike with startling images far beyond the norm, soon swept across the continental birthplace of modernism.

“I think it’s a very attractive image, it’s very modern, it’s by an artist who is largely unknown, and I feel privileged to help bring her more visibility,” Cateforis says. “I had the opportunity here to expand the canon, and that’s exciting.”

Six years in the making—a project that Cateforis began at the invitation of Richard Carlin, at the time Oxford University Press’ executive editor for higher education books in music and art—Modern Art is the first survey textbook to include people and regions “that have not been part of the narrative before,” including artists from Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East.

“This book is not quite encyclopedic, but it is certainly broad and extensive,” Cateforis told Rick Hellman, j’80, of KU News Service. “I think that is an important contribution, representative of the global turn in the discipline of art history.”

And yet, the titans still loom large. For the big book’s all-important introduction—a ho-hum opening would not have boded well for the long journey ahead—Cateforis compared a pair of contemporaneous train images from late 19th century Western Europe: Arrival of a Train at Vienna Northwest Station, an 1875 painting expertly rendered by Karl Karger in what Cateforis describes as an illusionistic style, alongside The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train, painted in 1877 by the Impressionist master Claude Monet.

Obvious visual differences, of course, are striking, yet Cateforis contends that the stories presented by these two works also provide context for the birth and role of modernism.

With his traditional use of artistic conventions, Karger delivers an image of formal composition, with passengers depicted so precisely that social status would have been immediately identifiable to viewers of the day. Lifelike colors are used throughout, and Karger’s dexterity with perspective devices creates spatial recession into a cavernous train station. The painting was so successful that, following its 1875 Vienna debut, Arrival of a Train at Vienna Northwest Station was acquired for Austria’s national gallery.

“To most twenty-first century viewers, however, Karger’s picture appears like a quaint artifact from a bygone time,” Cateforis writes, “whereas Monet’s still conveys a vivid and relatable sense of the experience of modernity.”

A mere two years later, Monet, painting “in a technically innovative way,” treated a similar topic with a fresh outlook that “invests his picture with the quality of discovery.” One angry critic argued that Monet’s painting was “filled with black, pink, gray, and purple smoke” that evoked nothing more profound than “illegible scrawl.”

From the distance of time, however, it is evident that Monet depicts the arrival of a train at the Gare Saint-Lazare with an enthusiasm that should remind us that in the 1870s, trains and their stations, and such pleasures as leisure-time excursions to the countryside, were new. Unlike Karger, who presented the novelty of train travel by draping it in staid societal conventions, Monet identified the event as distinctly modern.

“I think the key word is ‘innovation,’” Cateforis says. “Innovations in the arenas of science and technology, and industry, and commerce, and communication, and entertainment—all the various ways in which modernity transforms the experience of people—particularly in industrialized, highly developed societies.

“Art is participating in that process of change and discovery and innovation, and, furthermore, overturning traditions and conventions that people accepted and may have found reassuring. Modern art is often upsetting or causing controversy because of its experimental or exploratory nature.”

Cateforis carries the theme—and brilliantly pushes the first steps of his long exploration of modern art beyond its European roots—by next introducing Hazy Moon at Ushimachi, Takanawa, between Tokyo and Yokohama, an 1879 color woodblock print in the style known as ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world). The artist, Kobayashi Kiyochika, imagined an American-style locomotive, then unknown in Japan, traveling through the night on a railway that had been constructed only seven years earlier. The train’s artificial, Industrial Age lights contrast with the moonlight reflecting off water, representing traditional Japanese reverence for nature scenes. Even the woodblock print’s collaborative creation process, Cateforis writes, predicts modern art’s later acceptance of artists such as Andy Warhol and Bridget Riley employing assistants.

“One of the things that I hope the book does,” Cateforis says, “is make accessible and provide ways of thinking about and understanding modern art’s innovations, so they aren’t just seen as shocking and upsetting, but actually exciting and progressive.”

Exciting and progressive: exactly the tone Saralyn Reece Hardy, Marilyn Stokstad Director of the Spencer Museum of Art, uses when describing her late friend Virginia Jennings Nadeau, f’57, the Kansas City arts patron who, with her late husband, Richard, purchased Arena for their private collection and later bequeathed the colorful piece to the Spencer.

“[Elaine de Kooning] was very interested in dance. She had experience working with Merce Cunningham, and I think that awareness of movement is very evident in our painting,” says Reece Hardy, c’76, g’94. “It’s less a painting about a fixed state and more about the dynamism of a moment and the fleeting nature of time as figures move through it.”

Shortly after an amicable separation from her mentor-turned-husband, the abstract expressionist artist Willem de Kooning, Elaine decamped for Albuquerque, where she taught at the University of New Mexico. She became fond of making the five-hour drive to Ciudad Juárez, where, sketchbook in hand, she attended bullfights, later creating a series of paintings inspired by her immersion in the vibrant border city.

“Ours,” Reece Hardy says of the Spencer’s de Kooning, “is almost as if the figure is turning, and that—the turn—is where all the excitement is in life. It’s the unexpected, the excitement. Virginia saw this painting and she just fell for it. She said, ‘It was something I couldn’t walk away from.’ This was the symbol of Virginia.

“She had that dynamism and flair. She believed in livable elegance, because she was an interior designer, but she was not a format; she was about expressing individuality, and she was a color expert. She was known for bringing colors together in ways that other people would never have thought of, and I think that is also true of Elaine de Kooning—bringing colors together not as a study, but as a dance, an experiential exercise.”

Born in 1934 in Independence, Missouri, where her family owned Jennings Furniture Store, Virginia Jennings came to KU to study fashion illustration and, after her 1957 graduation, studied at the Parsons School of Design in New York City. A remembrance published by the Jackson County Historical Society after her 2020 death described her as, among other endearing traits, tall, elegant, charming and intelligent, with a twinkle in the eye that made others feel, in the words of a former student from her stint as a high school art teacher, “as though we shared a secret.” Recalled Independence

Mayor Eileen Weir, “Virginia is the person you want to sit by at a dinner party.”

The icon of Kansas City society and arts patronage—an embodiment, in Reece Hardy’s words, of Kansas City and Lawrence’s shared history of expressing “civic pride through cultural heritage and cultural futures”—was already on the Spencer’s advisory board when Reece Hardy was hired as director in 2005. Reece Hardy recalls meeting Virginia and Richard Nadeau at her introductory talk and promptly becoming enamored with “a radical couple” who “had their own vision of what life should be like, and art was at the very center of it.”

The Spencer chose to hang Arena in the Michaelis Gallery to honor the gallery’s stated theme: empowerment. With the equally powerful works by Nevelson and Murray that Cateforis analyzed at his April 13 gallery talk, and many other clustered in the vicinity, Arena highlights the gallery’s intention to, in Reece Hardy’s words, “bring attention to the power of women in the arts.”

“Throughout the museum, you will see many underrepresented voices whose day is way overdue,” Reece Hardy says. “And those are not only women, but the varieties of people and varieties of artists who haven’t had their place in the in the spotlight. We have brought them out. When you walk through the galleries, you’ll see some of your old favorites mixed in with things you didn’t even know we had. We want to open doors for our audiences to see that art comes from many, many different places and ways.

It’s all deliberate.”

Before publishing Modern Art, one of Cateforis’ recent forays into public arts outreach was the 2015 Lawrence Arts Center exhibition, co-curated with Ben Ahlvers, on Albert Bloch, a prominent member of the modernist European group of painters known as The Blue Rider and later professor and chair of the painting department at KU.

Before the Bloch exhibition, Cateforis was probably best known outside of KU’s art circles as a collaborator on the 2002 second edition of Art History, the seminal survey textbook written by Professor Marilyn Stokstad, who retired in 2002 as the Judith Harris Murphy Distinguished Professor of Art History and died in 2016.

Stokstad’s book instantly became the field’s flagship, and Cateforis says he took lessons as well as inspiration from his collaboration with his celebrated colleague when he set out to write his own book with similar aspirations for lasting influence.

“That was a generation ago,” Cateforis says, “but, because I worked on the chapters on modern art, it gave me the confidence to be able to write my own book. I can only hope that my book has some fraction of the impact that Marilyn Stokstad’s book had, but, whether it does or not, I’m proud of it.”

His pride is well earned: Unlike many other academic publications of such breadth and depth, Modern Art was written entirely by Cateforis, including a detailed table of contents, deeply researched notes and glossary, and a comprehensive index.

Standing alongside Art History, Modern Art bolsters the art history department and museum’s already strong national and international reputations, established in the modern era by giants of the field such as Charles Eldredge, Hall Distinguished Professor Emeritus of American Art and Culture, and buoyed by alumni who have soared to impressive heights, including, most recently, Stephanie Fox Knappe, g’00, PhD’14, who in June became the senior curator for global modern and contemporary art and head of American art at Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and Randall Griffey, g’94, PhD’00, who in 2022 was named head curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where he follows a strong Jayhawk tradition.

Eldredge, a KU professor and director of the Spencer in the 1970s, left KU to direct the Smithsonian American Art Museum from 1982 to 1988. His successor and former student Elizabeth Gibson Broun, c’68, g’69, PhD’76, directed the Smithsonian museum from 1989 until her 2016 retirement.

“It’s a point of pride, and it is legacy,” Reece Hardy says, referencing the Stokstad and Cateforis books as well as the long history of superior art history scholarship existing in concert with KU’s world-class campus art museum. “It’s a legacy to be artistic. It’s a legacy to artistic scholarship. And it’s a legacy to the artistic imagination as it is manifest in museums and universities.”

This, it could be said, is such a treasure.

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Portraits by Steve Puppe

Modern art images courtesy of Spencer Museum of Art

Karl Karger, Claude Monet and Kobayashi Kiyochika train images courtesy of Oxford University Press

/