Rural renewal: KU alumna restores buildings, bustle in Wilson, Kansas

Issue 3, 2023

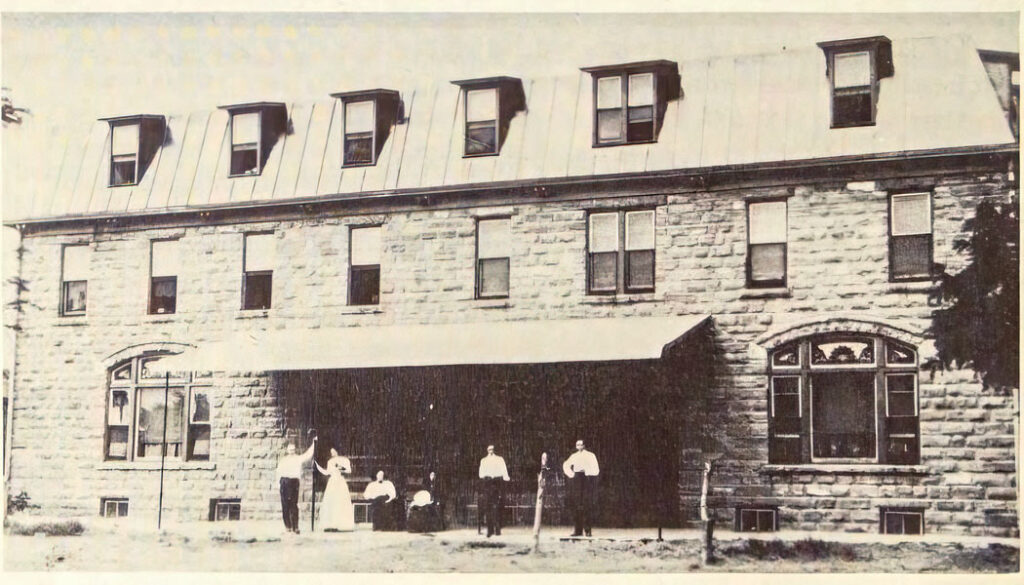

The Midland Railroad Hotel welcomes visitors to Wilson today in much the same way it did over a century ago, when the town was a midway stop between Kansas City and Denver on the Union Pacific Railroad. Inside the stately, three-story limestone building with the red roof, guests still enjoy cozy accommodations surrounded by refurbished original woodwork and other trappings of a bygone era. But unlike long-ago railroad travelers, many of the Midland’s modern-day patrons consider the hotel itself the destination.

“Coming to the Midland is like stepping back in time,” says Melinda Merrill, g’03, who has owned and operated the hotel since 2014 and turned the once-shuttered landmark into a renowned regional hub. “It’s a place where people can relax and get away from their day-to-day grind, and a place where people can just enjoy being in a small town.”

The hotel is one of a handful of revival projects Merrill has been involved with in the rural community of Wilson, population 859, about 180 miles west of Lawrence via I-70. The structures under her stewardship, which also include a repurposed grade school and a rescued tin barn, take on new lives and, in turn, provide new opportunities for hospitality and connection in a place once short on such amenities.

“The motivation started as not wanting to see these buildings torn down or fall down,” Merrill says. “But as I got immersed in the culture of Wilson, I saw what a special place it is.” Her goal gradually morphed into a larger mission to promote the town, which boasts unique charm as the self-billed Czech Capital of Kansas and host of the annual After Harvest Czech Festival every July. “For people to come and spend any significant time in Wilson, there has to be somewhere for them to stay,” Merrill says. “So the hotel is kind of the backbone in making this a stable community.”

A fully operational hotel makes travel to Wilson and its neighboring attractions—including Wilson Lake and the quirky art enclave of Lucas—far more feasible, and visitors boost more than the economy. “You don’t often see towns of this size with the kind of entertainment and events and dining that Wilson has thanks to the Midland,” says Christy Dowling Thomas, a board member of the Wilson Tourism Hub. “The hotel not only brings people in and makes them want to come back, but it’s big for the people who live in town and this part of the state in terms of taking pride in the area.”

Growing up, Merrill relished summer stays at her grandparents’ farm near Wilson and, later, at their home in town. “My dad was in the flour milling business, so we moved a lot,” Merrill says. “The one constant was coming to Wilson. I had an affinity for it even then. For me, it was always a matter of coming back here.”

Her connection to KU was similarly strong. Her mother, Virginia Urban Merrill, c’47, studied speech pathology at the University, and her late father, Fred, ’47, attended before serving in the U.S. Army. In 1990, Merrill’s parents endowed the Merrill Advanced Studies Center, one of 14 centers within the KU Life Span Institute, an internationally known hub for human development research and policy. The Merrill Center hosts research retreats, publishes findings and sets policies for future studies. “My parents believed in higher education and wanted to support the research and collaboration that happens at universities,” Merrill says. “They saw that as a need in society.”

Merrill graduated from Colorado State University with a bachelor’s degree in sculpture and worked as an artist and in art galleries until she pursued a teaching career. She earned her bachelor’s degree in elementary education from the University of Saint Mary in Leavenworth and began teaching in Kansas City. In 1995, she attended a KU symposium on gifted education. “It was an amazing new world for me,” Merrill says, “and I enrolled in KU after that.”

She continued teaching while completing her master’s in curriculum and instruction in the School of Education & Human Sciences. She focused on gifted education, and says learning how to foster creative problem-solving skills in her students has served her well in the hospitality business, where the unpredictable reigns. “You learn not to panic,” she says. “When something goes wrong, the mindset is, ‘How can we make this work? What can we change? What strategies can we use?’ I truly think that came out of my time at KU and my gifted-ed degree. It taught me a whole different way to think.”

After graduation, Merrill taught gifted education in Kansas City and later in Estes Park, Colorado. In 2009, she retired from teaching and moved to Wilson part time to manage her family’s farm, and the big brick building sitting vacant in the center of town captured her interest. A plan to convert the former grade school, built in 1916, into an assisted living facility had fallen by the wayside, but Merrill still saw potential. “I’d consider myself a conservationist,” she says. “I believe in making use of what already exists, even if it takes some reengineering.” She purchased the school in 2012 and oversaw its overhaul into a 17-unit apartment complex. Her vision and follow-through on the venture caught the attention of a group of local leaders looking to ensure the long life of another Wilson landmark.

Built from central Kansas’ distinct post rock limestone, the Midland opened for business in August 1899. Originally known as the Hotel Power, it was renamed around 1902, following a fire that destroyed much of its interior. A brick addition in 1915 expanded the hotel, which today offers 28 rooms. Located just 200 feet from the train tracks, the Midland prospered throughout the 1920s and was a popular stop for traveling salesmen, who would display samples of their merchandise in the hotel’s basement. The Midland remained in operation for nearly 90 years, until 1988, chugging along even after the Union Pacific discontinued passenger service in the early 1970s.

When the building went on the market in the late 1990s, a group of town leaders formed the Wilson Foundation and bought the abandoned, dilapidated property. Over the next few years, the foundation secured grants and donations that would go toward recapturing the Midland’s original look and feel. The sweeping restoration began in 2001. “They took out all the woodwork, refinished it and reinstalled it,” Merrill says, noting that such commitment to authenticity touched every facet of the hotel’s renaissance. “They did a beautiful job.”

The Midland reopened in 2003 and changed hands twice over the next decade. In 2014, when the owner was looking to sell, members of the Wilson Foundation approached Merrill about potentially buying the hotel. While her primary objective at the time was to preserve another antique structure, she was also optimistic the hotel could flourish. “I thought, ‘We’re 2 miles off I-70 and just a few miles from Wilson Lake,’” she recalls. “I figured I could make it work.”

It has worked indeed, thanks in large part to Merrill’s efforts to reimagine the Midland as not just a place for passers-through. Alongside the old-meets-new comforts of the revamped hotel, today’s Midland experience features a rich mix of social happenings presented throughout the property’s assorted spaces: a full-service restaurant, The Sample Room, located in the basement and named as a nod to the downstairs’ early use; a vibrant outdoor tract complete with two fire pits, flower and vegetable gardens, and a chicken coop; and Merrill’s newest acquisition, The Barn, a 1906 stable relocated just east of the Midland that she has transformed into a bar and event venue.

Live music, themed dinners, corporate retreats, wine tastings, art showcases and more bring locals and out-of-towners alike to the Midland, often on a recurring basis. “The activities give people a feeling of connection and ownership,” Merrill says. “They’re not only coming to the Midland, but they’re taking part in something special. It has been gratifying to watch the friendships that have formed among the people who come here regularly.”

May through October is the busy season for Merrill and her staff of 20 to 25. Rooms sell out for July’s Czech Festival months in advance, and many outdoor enthusiasts bound for Wilson Lake make the Midland their home base. The Sample Room serves dinner six nights a week, with comfort foods like chicken-fried steak and meatloaf always on the menu. Merrill maintains a robust online presence for the hotel, which she credits with helping spread the word to travelers searching for accommodations. Guests have come from across the U.S. and numerous countries, and Merrill says the people she meets are her inspiration to stay the course. “The folks who come through the hotel are absolutely phenomenal,” she says. “Most have an appreciation for the history of the building, for the building materials, for nature. I learn so much from them.”

Many small towns have a Midland of their own—a relic from a different, perhaps livelier time that still looms large, for better or for worse. “Buildings like the Midland were built well and don’t deteriorate rapidly, so they can either sit empty, as an incredible eyesore for the community, or they can be an anchor for the community,” says Marci Penner, author of The Kansas Guidebook for Explorers and co-director of the Kansas Sampler Foundation, which works to spotlight and sustain the state’s rural communities and culture. “In the Midland’s case, it has definitely become an anchor.”

Penner, c’79, whose work has taken her to each of Kansas’ 627 incorporated towns and cities, commends how Merrill has blended historic appeal with modern purpose. “There’s always a fine balance between honoring the past and making sure you’re moving forward, and I think the Midland is a perfect example of achieving that balance,” Penner says. “Melinda honors the past by keeping the Midland in great shape, and all the events she hosts honor the present by providing what people are looking for today.”

Merrill aims to improve some aspect of the Midland every year, ever mindful of ways she can help Wilson thrive. “I feel good that we’ve been able to give a nice foundation to a rural town,” she says. “I want people to come to Wilson and go, ‘Oh my gosh, I love the fact that we’re here. This is exactly where we want to be.’”

She hopes the Midland and Wilson can inspire tourism to other small towns as well, and she thinks fellow Jayhawks in particular would delight in discovering some of the Sunflower State’s lesser-known nooks. Says Merrill, “All of Kansas is Jayhawk country.”

Stone age

Post rock limestone, used to construct the Midland Railroad Hotel and several other buildings in Wilson, is the upper layer of the Greenhorn Limestone formation, which stretches through 18 central Kansas counties. The material was formed from sediment deposited during the Cretaceous Period, from 145 to 66 million years ago, when much of the state was under water.

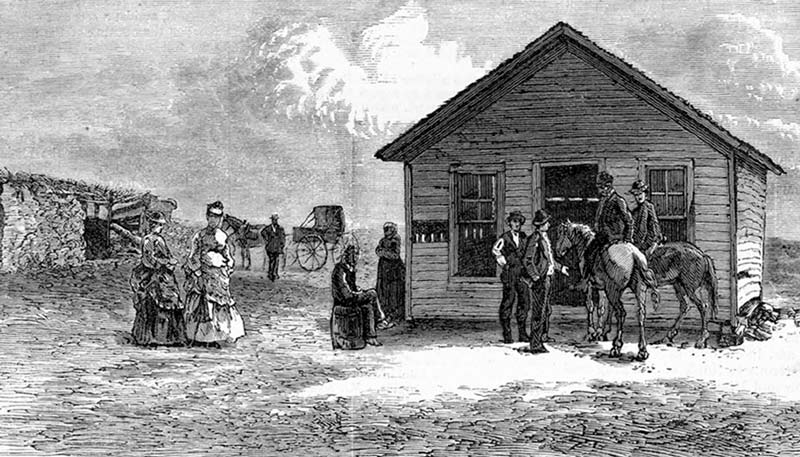

The rock layer, typically 8 to 12 inches thick and located relatively close to the surface, furnished an ideal building material for those settling on the wide-open Kansas prairie in the mid- to late 1800s. With scarce trees to use as lumber, they quarried and shaped post rock limestone to fashion all manner of infrastructure, from homes and businesses to bridges and the region’s characteristic limestone fence posts. State Highway 232, an 18-mile route that connects the towns of Wilson and Lucas, has been designated the Post Rock Scenic Byway by the Kansas Department of Transportation and offers glimpses of the native stone as fence posts and farm buildings. “There’s a whole life to this limestone,” says Midland owner Melinda Merrill. “It reflects both the history of the land in this part of the country and the work ethic of the people who built with it.”

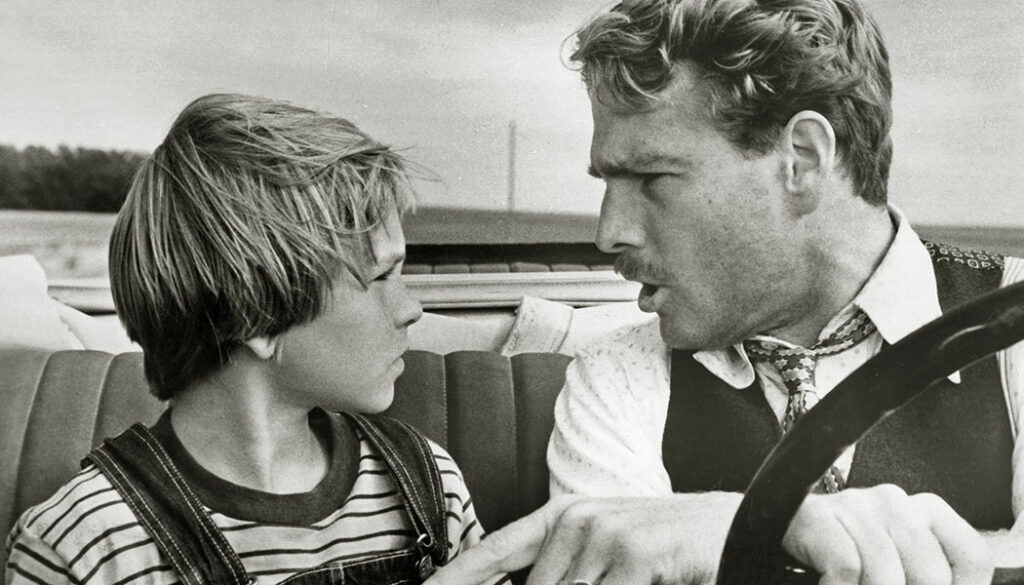

The Midland’s Hollywood moment

The 1973 movie “Paper Moon,” starring Ryan O’Neal and his daughter, Tatum, filmed scenes in several Kansas locations, including at the Midland Railroad Hotel in Wilson. Set during the Depression, the story follows a con man, Moze, who is saddled with transporting an orphan, Addie, across Kansas to her family in Missouri. The two team up to pull off a string of scams, forming an unlikely bond as they swindle and try to stay

a step ahead of the law. For her performance, 10-year-old Tatum became the youngest actor ever to win an Academy Award.

On a Friday evening in May, about 150 people gathered on the Midland’s back patio for a showing of the movie on the building’s limestone exterior, part of the two-day Paper Moon Festival in Wilson celebrating the film’s 50th anniversary. Several area residents who were present during filming stopped by the Midland to share memories, among them two brothers who appeared as extras in the movie when they were young children. “We had a great turnout, with people from as far away as San Diego,” Melinda Merrill, owner of the Midland, says of the festival, which also featured a walking tour of Wilson filming locations, an antique car display and activities for kids. “The movie is such a fun piece of history for Wilson and something people in town still unite around.”

Megan Hirt, c’08, j’08, is assistant editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

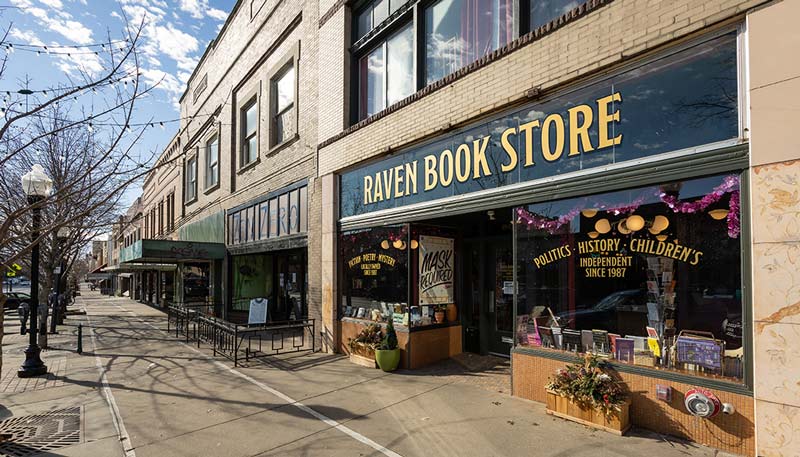

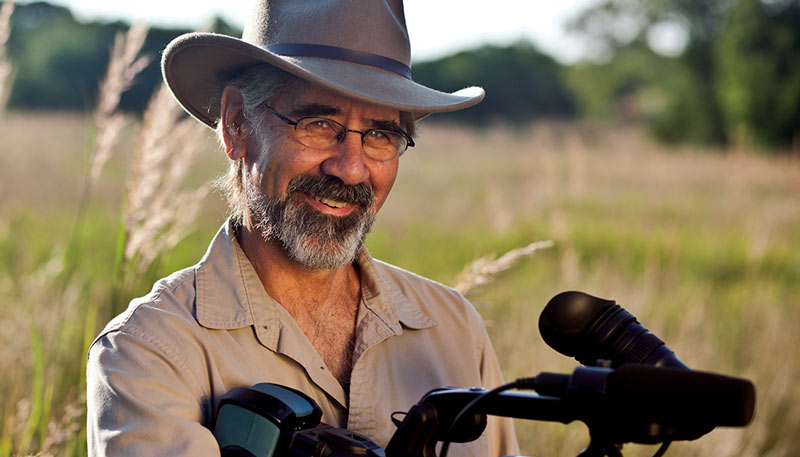

Photos by Steve Puppe

Archive hotel photo courtesy of University Press of Kansas

Post rock limestone photo by N. Nehring/iStock

“Paper Moon” photo by Paramount Studios/Alamy

/