Swiftology: Taylor Swift inspires KU professor’s teaching, research

Issue 3, 2023

July 7 has arrived, the sun has risen, and Kansas City is waking to the Taypocalypse.

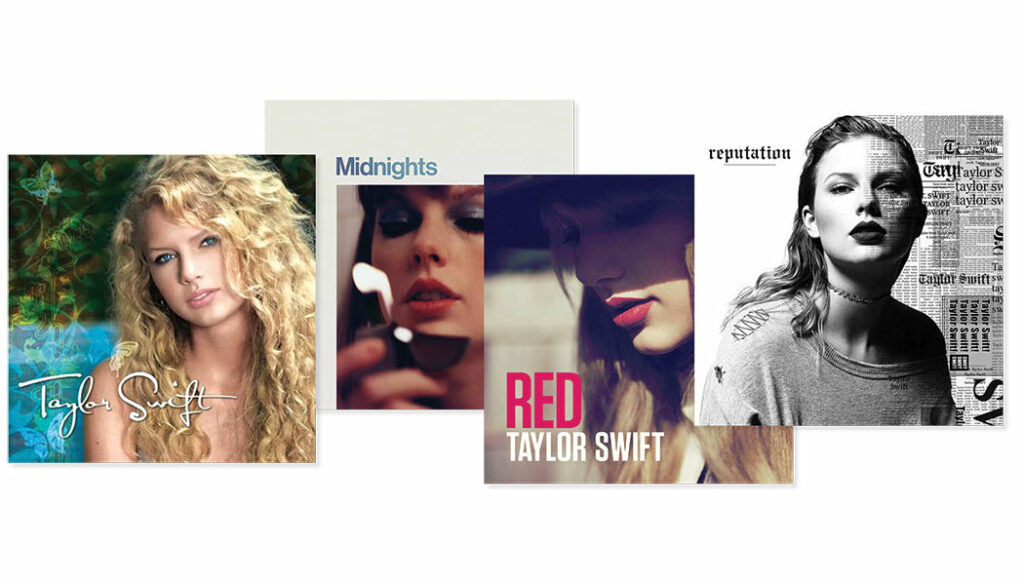

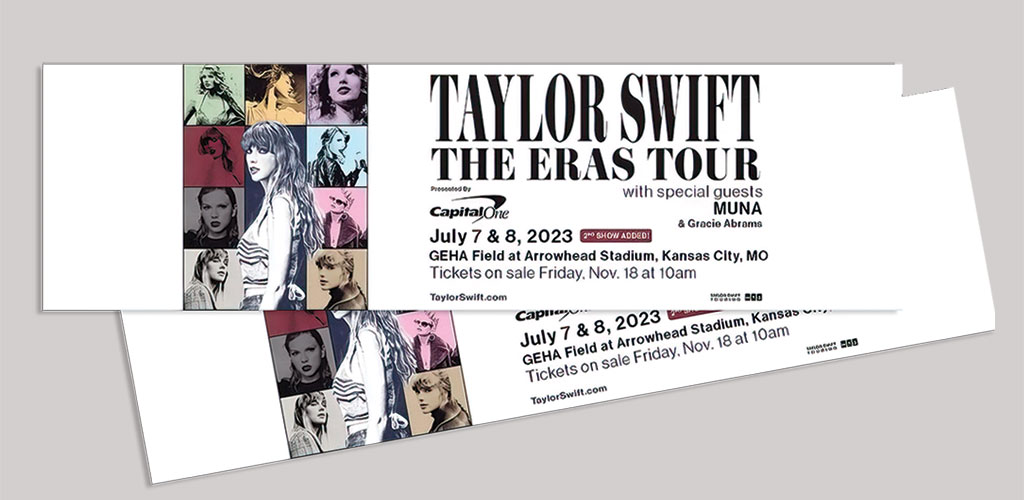

The economic and cultural juggernaut that is Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour has thundered into town for two long-awaited shows at Arrowhead Stadium. My 14-year-old daughter is out of bed shockingly early for a high school student on summer break—especially considering that last night, at 11 p.m., Swift dropped her latest album, the rerecorded Taylor’s Version of her 2010 LP “Speak Now,” the most recent flex in the 33-year-old global pop star’s ongoing power move to reclaim control of her back catalog by releasing note-for-note reconstructions of early albums whose master tapes were sold against her wishes. Any new music release—even new old music—is a major happening for millions of Swifties (as the worldwide community of hardcore Taylor Swift fans call themselves) who analyze and debate every song lyric, Instagram photo, tweet and snippet of stage patter like scripture.

The buzz this morning, my daughter tells me, is that Swift changed a lyric in one of her “Speak Now” songs that some fans and critics had deemed sexist. This development is not entirely surprising, but still thrilling for the Swiftie legions who stayed up half the night playing, deconstructing and discussing the new release. This is the first of what will be many news flashes today. My daughter, against all odds, has landed tickets to one of the Kansas City shows, defying scalper bots and Ticketmaster’s meltdown, thanks to the help of her mother, aunt and cousin, who spent hours online during the Nov. 15 presale. It takes a village to raise a Swiftie.

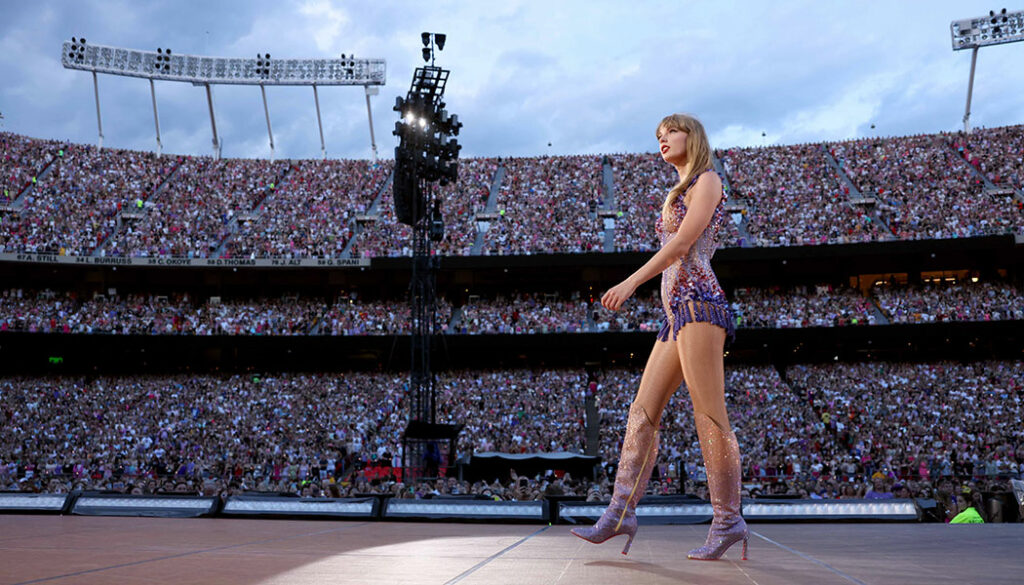

The Eras Tour will inject around $4.6 billion into the U.S. economy and is expected to propel Swift herself to billionaire status. More than 110,000 ticket holders will pack Arrowhead for the Friday and Saturday night concerts, and many of them will be screaming teenage girls. But not all. Also out in force will be Taylor mamas introducing their daughters to Swiftie culture, Swiftie dads gamely sporting themed T-shirts emblazoned with song lyrics, college students attending their third or fourth show in the retrospective journey through the singer’s 17-year career, plus Gaylors, OG Swifties and a host of other subgroups that defy the common stereotype that the obsession with all things Taylor is exclusively a teen mania.

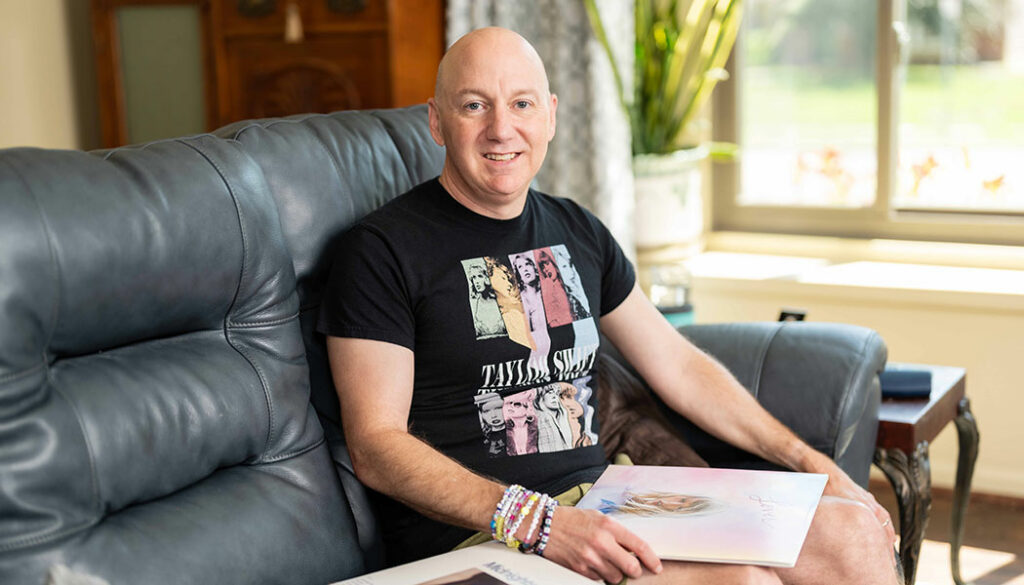

Among them will be a 51-year-old KU sociology professor whose scholarship and award-winning teaching focus largely on cultural sociology, which is concerned with the study of societal institutions, norms and practices. The author of three books that have peered into popular culture’s seedier corners, Brian Donovan will bring to his first Taylor Swift show the dual interests of a social scientist and a fan. Thanks to a research pivot that has its roots in the COVID-19 pandemic, the professor and self-described Swiftie is now concentrating his teaching and scholarship on the entertainment icon—in particular, on a product of her music and the community around it that is more difficult to quantify than tax revenue and other economic boosts, but that is essential for human well-being:

Joy.

Donovan joined the KU sociology faculty in 2001 and for two decades has taught the department’s class in cultural sociology. The class explores popular culture, and in the past few years the professor noticed that students often mentioned Taylor Swift in class discussions. Those references increased during the pandemic, which coincided with an uptick in Donovan’s own interest in Swift’s music.

He has considered himself a “low-key” fan since 2014, having bought Swift’s fifth album when it came out.

“I was really late to the party, but I fell in love with ‘1989,’” Donovan says. “I thought it was a perfect pop album. But I didn’t consider myself a Swiftie.”

He listened to her next album, “Reputation,” and followed the celebrity news about her feud with Kanye West and Kim Kardashian. A documentary on Swift, “Miss Americana,” provided a glimpse into her private life and hinted at a greater depth lurking behind her public persona.

But it was the pandemic that moved Donovan from casual fan to Swiftie. In 2020, while presumably on lockdown like many of her fans, Swift made two spare, folk-influenced albums. As families coped with isolation and schoolchildren’s relationships with friends and teachers suddenly narrowed to computer screens, Swift’s “Folklore” and “Evermore” arrived like a double shot of hope. Hearing her music ringing out during breaks from Zoom school offered consolation that at least some of the traditional delights of childhood were still there for the taking.

“When she released those two albums and I heard the song ‘The Last Great American Dynasty,’ something just clicked,” Donovan says. “That song seemed so brilliant to me that I just fell down the rabbit hole. I was listening to her back catalog and realizing I’d had a lot of preconceptions about her as a musician. I realized what a genius she was.

“I can claim that I was a fan during the ‘1989’ era, which is true, but like a lot of men my age, I only started to identify as a Swiftie in the ‘Folklore’ era.”

At KU Donovan has won several awards for his work in the classroom, including the Gene A. Budig Award for Excellence in Teaching. His classes often deal with tough topics: poverty, health disparities, racial and gender inequality, human trafficking, genocide, intimate partner violence. His three scholarly books tackled white slavery, sex crimes and the negative impacts of the gold digger stereotype.

All part of the territory for his field of study.

“Sociology as a discipline is extremely good at analyzing suffering and inequality,” Donovan says. “And we should study those things for sure. But we are, I think, less able to talk about joy and happiness. We tend to give those topics to the psychology department.”

But in the early days of the global pandemic—as health care professionals struggled to develop effective COVID treatments, the global economy tanked, and the delivery of a successful vaccine was far from assured—a change in tone seemed called for.

“There was this sense of maybe I could do something in these pandemic times that’s more upbeat, that isn’t about human suffering as much,” Donovan says. “Focus on something that’s more joy-producing.”

Thus was born The Sociology of Taylor Swift, an honors seminar that (according to the syllabus) uses the pop supernova’s life and career “as a mirrorball to reflect on large-scale processes like the culture industry, celebrity, fandom, and the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality in contemporary American life.” The class, new this fall, will explore many of the cultural sociology topics Donovan normally teaches, such as the construction of authenticity, symbolic boundaries and gatekeeping, fandom and fan labor, and celebrity politics. “We will also use recent controversies and legal conflicts involving Swift,” the syllabus continues, “to examine questions about intellectual property, copyright, and the economics of creative industries.”

There will undoubtedly be some time for sampling Swift’s catalog of 200-plus songs and viewing her music videos. But The Sociology of Taylor Swift will not be a fawning fanfest. By analyzing the sprawling cultural impact of her superstardom, by comparing how popular media depictions of Swift differ or align with academic analysis of her celebrity and her fandom, the class will explore weighty topics.

“Let’s carve out a space for happiness,” Donovan says of his concept for the seminar. “At the same time, some of the conversations I hope we have in class do get at some of the more serious questions about race and gender in American society. You know, is Taylor Swift a good ally? She says she’s a feminist: What kind of feminist is she? Most of her fan base are white women: Is there room for folks from marginalized communities within this largely white fan base? Those are some of the conversations that I hope we have.”

Donovan’s wife, Natalie, is an occupational therapy assistant whose work in nursing homes meant she was “bringing home a lot of doom and gloom” during the pandemic. At the same time, her husband, in his role as associate chair of the sociology department, was scrambling to find alternative ways to deliver classes at a time when the traditional college campus experience seemed imperiled. She says the emphasis on positivity was a welcome departure from the grim mood of those days, and she believes the pivot has boosted his teaching—never low-energy—into a higher gear.

“He has always been a very enthused teacher, but he is so passionate about this subject and it is something that brings him such joy that I see this extra huge twinkle in his eyes, and he wants so much to share what he’s thinking and learning,” she says. “He really is like a street preacher out there, trying to get everyone into it. He’s keeping it very professional, with good academic boundaries, but I can tell there is a part of him that just wants to explode with some song lyrics.”

The Sociology of Taylor Swift is one of several first-year seminars meant to foster community within the University Honors Program, and to the extent that it will likely attract Taylor Swift fans—which Donovan absolutely expects it will—community will already be built in. Swifties are a close-knit tribe.

He learned as much when he discovered TikTok. Already an enthusiastic social media convert, Donovan sought out the video platform because his students were referencing it in class, and he thought he should try to understand the new tech capturing their attention. “Finding students where they are” is a phrase that comes up often when he talks about his teaching, and where his students were, it turned out, was on TikTok. So he joined.

Exploring areas devoted to Swifties, he started to notice the social organization of the fandom, the different subgroups within the larger whole, and the “meaning-making practices” they engaged in. The sociological term refers to how people build culture within a community.

“They’re speaking a similar language; there are inside jokes and references that only other Swifties would know,” Donovan explains. “There’s toxicity in any fandom or in any group of people, honestly. But I was impressed by a lot of the warmth and just genuine sort of happiness that I saw. What sociologist Émile Durkheim called ‘collective effervescence’: people getting excited about being in a crowd.”

Hardcore Swifties engage in “clowning,” which is a search for “Easter eggs” and other hidden meanings and secret messages not only in Swift’s song lyrics, but also in her social media posts. To be a Swiftie is to be a detective, searching for clues that hint at the timing or content of future music releases or concert set lists and unraveling any number of conspiracy theories about her tangled romantic life. Some of this is encouraged by Swift herself and some is the result of certain subgroups within the fandom, but clowning is approached at an ironic remove: We know our obsessiveness is a bit much, Swifties seem to signal, but it’s mostly harmless because it’s all in fun.

A classic example, Donovan says, is a 2019 Instagram post from Swift that included a photograph of her peering through a fence with five holes in it. Swifties interpreted the image as a tip that her highly anticipated new album “Lover” would be released in five days. That didn’t happen, but Swifties still talk about how much they loved the game.

“Sociologically, that is fascinating: It’s almost like these millenarian cults that think a new social order will come into being on, you know, July 7th, and then it doesn’t happen, so they come up with a new theory,” Donovan says, chuckling. “She’s brilliant at marketing. She knows she is keeping us on tenterhooks, and she knows that she is keeping the energy level high in the fandom.”

A photo of a pop star looking through a fence (or, for that matter, the topic of pop culture in general) strikes some as a subject unworthy of serious academic study, Donovan knows, but the episode is an example of how human beings build social capital. Such posts get people talking. “It provides a pretext for those conversations and allows fans not just to feel closer to one another as fans, but to make a human connection they might not get in their family life or their work life,” he says.

“It’s making a meaning out of something that is completely trivial. It doesn’t affect the war in Ukraine or climate change, but it’s a way that people are finding some joy in their life.”

Donovan eventually came to see that the Swiftie culture could be the focus of more than just a class: It could be the subject of his next research project and fourth book. After clearing it with the Institutional Review Board at KU’s Office of Research, he put out a call on his Taylor Swift fan site on TikTok asking Swifties to contact him if they were interested in being interviewed for “a new sociological study on the Swiftie fandom … that will help us gain a better understanding of the social dynamics of fandom and how fandoms produce joy and collective identity.”

Responded one TikTok wag, “Your sample size is about to be wild.”

Indeed, Donovan’s inbox blew up with more than 1,600 replies—many long testimonials about how much Swift’s music meant to respondents. He has interviewed 50 so far, gathering material for academic papers and a book. Specifically, Donovan says, he’s interested in the development of social capital among the fans and in rethinking the idea that “parasocial relationships” (one-sided relationships in which one person extends emotional energy, interest and time, while the second party—often a celebrity or sports team—is completely unaware of the first’s existence) are necessarily a negative phenomenon.

“What I think is interesting about Swifties is that there is an element of hero worship in that we’re all kind of looking up to Taylor at the top of the mountain,” he explains, “but there’s also a lot of lateral connections that are being made among the Swifties themselves.”

Alexis Greenberg can speak to that. An Overland Park senior in the William Allen White School of Journalism on the strategic communications track and a longtime Swiftie, Greenberg was 16 when she started college, 17 when she transferred to KU with enough credits to take junior-level classes.

“Everybody’s 21,” Greenberg says of her classmates that first year on the Hill. “It’s hard to build a connection because there’s a big difference in college between a freshman and a senior. The first semester was difficult.”

What helped ease the transition was bumping into fellow Swifties on campus.

“More people than I could have imagined had Taylor Swift jackets, Taylor Swift hats, Taylor Swift bracelets,” Greenberg recalls. “I stopped almost every one and said, ‘What’s your favorite song on the new album?’ I got some of their phone numbers when I was here for freshman orientation. One girl had a Taylor Swift shirt on, and she and I still text every week. We didn’t have any classes together. We didn’t live in the same building. The only connection we had was Taylor Swift, but that was our way of making friends at KU and starting to build our own personal communities.”

That experience ultimately led Greenberg to organize Swiftie Jayhawks and to reach out to Donovan: She founded the KU Swift Society and asked him to serve as the faculty adviser. The official student club has around 70 members who meet regularly for Swift-themed get-togethers such as trivia, mocktails and crafts. Rather than merely lending his name to fulfill student club rules requiring a faculty sponsor, Donovan became an avid participant in Swift Society activities.

“I think he breaks a lot of the stereotypes about Taylor Swift fans by being, you know, not a teenage girl,” Greenberg says, laughing. “It’s really fun that he can engage with us about those topics. He’s got kind of a different angle coming from sociology. He’ll often sit down at a table with some of our members during an event and start a more philosophical conversation than just, ‘What’s your favorite song?’ or whatever. He comes at it from a really interesting perspective.”

This fall, she is one of Donovan’s seminar assistants for The Sociology of Taylor Swift.

“It’s gonna be really fun,” says Greenberg, who attended an honors seminar her first semester at KU. “It’s a pretty small class, like 15 people. All the honors seminars are really small, which allows for a great opportunity to connect with each person individually on a very personal level. My honors seminar assistants told us their favorite places to eat in Lawrence, their favorite places to study on campus, and just overall tips for being a freshman at KU.

“I think it’ll be a great way to make a difference, to impact more students at KU and kind of help them in their journeys.”

By 3 p.m. on Friday, the Arrowhead parking lot is nearly full. Swifties of all ages tailgate under shade tents, and the merch lines coiling around the stadium seem to vibrate with elastic energy. There’s a crackle in the air. No one seems the least bit bothered by the long wait or the blaring sun.

“You’re gonna see a lot of sparkles, a lot of pink, and some floor-length gowns,” my daughter tells me when I ask what to expect.

Indeed, Taylor Nation has turned out and dressed up in outfits reflecting their favorite Swift era: A young lady swathed in purple taffeta toddles by in a Lavender Haze, followed by an older man with a T-shirt that reads, “It’s me, Hi. I’m the dad. It’s me.” My daughter—in a white dress, bejeweled ten-gallon hat and cowboy boots—reps the “Fearless” era, which seems a popular choice with Cowtown fans. Swifties are trading friendship bracelets, volunteering to snap photos for strangers and generally frothing with anticipation. Gates open at 4. By 8, when Swift kicks off a show that lasts until nearly midnight, the collective effervescence is off the charts.

“I knew people would dress up, but in some ways the show felt like a Halloween party: If you weren’t in costume, you stood out,” Donovan says. He and his wife, Natalie, donned outfits showing Swift and her cats. For her Taylor tribute, Veronica Hill reached all the way back to the “Fearless” tour, which rolled into Kansas City in April 2010, when she was 21 months old.

Even from the parking lot, it’s easy to pinpoint the precise moment she takes the stage: The noise level from inside the arena, already seemingly pegged at 10, somehow kicks up a notch and the massive concrete bowl seems to levitate for a moment as 55,000 Swifties begin belting in unison with Swift the lyrics to “Miss Americana & The Heartbreak Prince.”

You know I adore you

I’m crazier for you

Than I was at 16

This one is going to 11.

Somewhere in the sea of singing Swifties is Alexis Greenberg. She attends with her father, Greg Greenberg, b’96, who manned the online presale to snag tickets to both Kansas City and New Jersey shows, and who also accompanied his daughter to Swift concerts in 2015 and 2018. “He’s definitely a Swiftie dad,” Alexis says. “He lets us paint his nails and put glitter on his face. He recognizes and appreciates how the shows build community.”

About 50 members of the KU Swift Society make it to an Arrowhead show—as does their faculty sponsor. Dressed in custom-made outfits that feature pictures of Swift with her cats, Brian and Natalie Donovan attend the Saturday concert. As the date approached, Donovan shared that he planned to go as a fan, but knew he’d likely be tempted to bring a notepad and pen to jot down some observations.

The after-action report tells a different story.

“I think he probably abandoned a large part of his ability to stand outside himself and observe sociologically, because he was so deep in the experience,” says Natalie Donovan, for whom the night marked a transformation from casual fan to full-fledged Swiftie. “I think all the yelling and him scream-singing along with everyone else was not conducive to note taking.”

“Once the music started, I was completely in fan mode, reveling in the moment,” Donovan says. But there was ample time for observation before and after the concert. What he saw reinforced his belief that Swift and her fandom are rich subjects for sociological study.

“Seeing strangers connect in a positive way—that’s always a good sign of the value of a given cultural phenomenon,” he says. “Anything that can move 55,000 people for good or ill is worthy of our attention.”

One fan Donovan interviewed through his TikTok outreach, a 30-something Swiftie with a high-pressure job, suddenly found herself stuck at home during the height of the pandemic. She noticed that another resident in her apartment building had a Taylor Swift doormat. She left the neighbor a note, and the women began texting, then talking—with masks, at a distance, in the hallway—before eventually getting together for an overnight listening party to celebrate the midnight release of one of Swift’s 2020 recordings. Three years later they’re attending together an event that seemed inconceivable during those dark days—an Eras Tour concert uniting thousands of thrilled fans—asking, for a few brief hours, nothing more than what we have always asked of our idols: joy and deliverance.

Why study Taylor Swift?

The weeks leading up to The Eras Tour were a carnival of hype, as Kansas City bars held Taylor Swift nights, restaurants renamed menu items for her songs, and a Missouri farmer created a gigantic crop mural of Swift’s face to welcome her to town. Local news offered wall-to-wall coverage of Swiftapalooza, drawing some predictable grousing from those who wondered why so much attention should be lavished on a mere pop star.

It’s a fair question, one that even some academics have posed: Why study Taylor Swift?

The better question, Brian Donovan says, is why study pop culture in general?

“Things that look trivial on the surface—pop music, TV shows, video games, sports teams—are important to the social order,” he says. “They’re important to people yearning for self-discovery and meaning, or searching for like-minded others to form bonds with. It’s how we make meaning in our lives. It’s how we find joy in our lives.”

Pop culture gives us a way to imagine a different way of living, Donovan says. “In that sense it can be a space of utopia and resistance, and at the same time pop culture can reflect and create all the negatives—the divisions and inequalities in all their various forms, such as class and gender.”

Consider the venue for Swift’s concerts: Arrowhead Stadium, home of the Kansas City Chiefs. Newspapers set aside whole sections and radio stations devote 24/7 programming to analyzing the feats that unfold there. When’s the last time you saw a letter to the editor complaining of that?

Swift talk and sports talk are similar, because neither “has any kind of real consequence for the way we live our lives,” Donovan says. “But it’s a way for us to build connections with people that we wouldn’t otherwise.”

There is perhaps another element at work, one that goes all the way back to the days of Beatlemania, when crowds of teenage girls screamed so loud the Fab Four couldn’t hear themselves play.

“With criticism of pop culture as a field of study, and especially the criticism of studying Taylor as being unserious, I think there is a kind of gendered assumption,” Donovan says. “The sociology of sports has a longstanding tradition. It’s been around awhile. But when it’s a phenomenon that is primarily enjoyed by girls and young women, I think some sexism sneaks into those assessments about whether it’s important or not.”

In the end, no one is arguing that we should study popular culture instead of climate change or gun violence or social inequality, Donovan says. We can do both.

“Academia is big enough that people can focus on these subjects that might seem unimportant, but are actually deeply consequential for the people who are bound up in them. Those domains seem trivial from the outside, but there’s a lot more going on than people think.”

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Top photo by John Shearer/Getty Images

Brian Donovan photos by Steve Puppe

Concert photos courtesy of Brian Donovan and Mary O’Connell

/