One of one: A vintage Mustang on the road to healing

Issue 3, 2024

For 20 years, Sam McGee was driven by a quixotic goal: to bring back into the family fold a 1968 Ford Mustang that had once belonged to his grandmother, Eva Corcoran McGee.

Sam is a car guy—and an aficionado of the sporty Ford coupes—from way back. His first ride was a classic 1966 Mustang, a restoration project that he and his father, Mike McGee, e’73, started together in the garage of their suburban Houston home before Sam was old enough for a driver’s license. He drove it throughout the 1990s in high school and while earning his bachelor’s degree at Texas A&M. The car was part of his identity. “Sam’s 66—it was who he was,” Mike recalls.

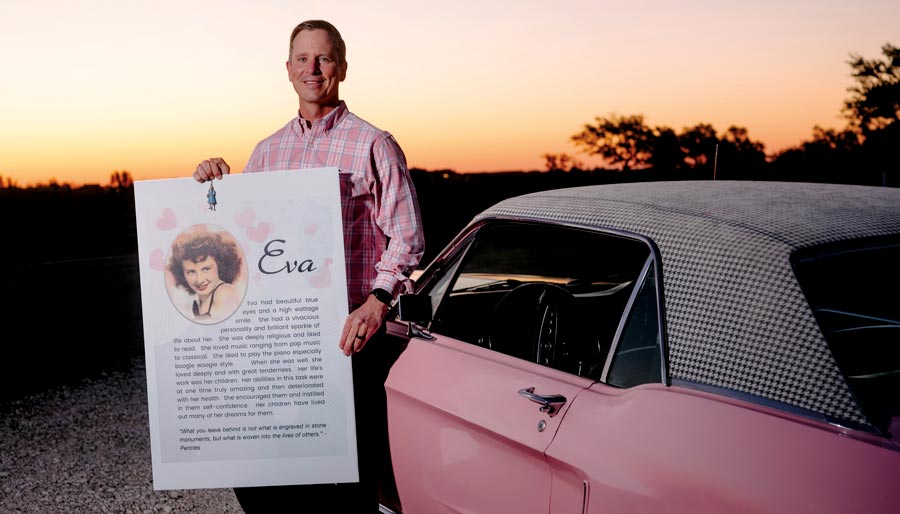

Now president of the Texas Hill Country Mustang Club in Boerne, Texas, Sam is still a car guy. But his decades-long quest to track down and buy this particular automobile was fueled by something other than the collector’s impulse to own a singular, strikingly iconic example of American car culture—which Eva’s Mustang, with its “Passionate Pink” paint job and black-and-white houndstooth check vinyl top, undoubtedly is.

Sam never knew his grandmother, who died two years before he was born. At the time of her death, the car was the most valuable thing she owned and her most prized possession. Tracking it down was a way to add a hopeful coda to a life story that ended in a tragedy that has echoed for 50 years through generation after generation of the McGee family.

As a bright, hardworking student at Norton High School in the 1960s, Mike McGee knew exactly where he wanted to attend college. During his childhood, the family moved back and forth between western Kansas and Colorado, and his father, David, who scraped out a living laying tile and linoleum, was an avid KU fan. David also had a volatile temper, which led to terrible fights between him and Eva and created a difficult home life for Mike and his two sisters. “School was a refuge for me, and I remember as a young boy saying, ‘When I grow up, I am going to create my own environment,’” Mike recalls. “I remember reading in the Norton Telegram, ‘chemical engineer, highest-paid four-year degree,’ and thinking, ‘That’s for me. That’s a way to change your environment.’” He came to the Hill to major in chemical engineering and set his sights on a career in the oil industry.

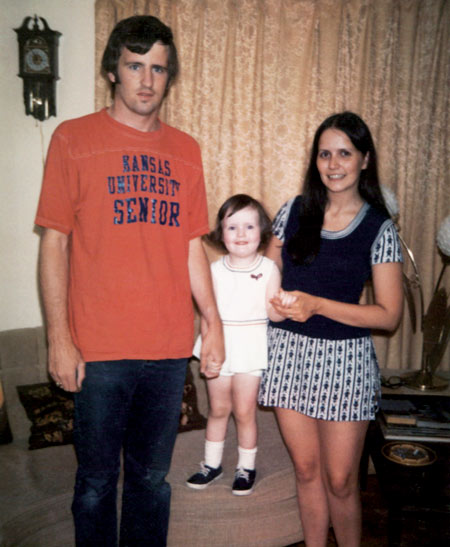

By sophomore year, he was married to his high school sweetheart, Sharon, with a baby on the way. The next summer, 1971, he was working at a grain elevator in Reager, an unincorporated community in Norton County, when he saw his mother’s bright pink Mustang heading west on Highway 36 toward Denver. It was the last time he saw her alive.

Eva had come from Denver to see Mike and Sharon’s baby, her new granddaughter, and now she was going home. “She just adored Amy,” Mike says. Mother and son had said their goodbyes already, so Eva did not stop at the elevator on her way out of town. “She just looked very determined,” Mike recalls. “Driving into the sunset.”

The following summer, Mike and Sharon stayed in Lawrence and did not see Eva. In February 1973, he received a phone call. His mother had taken an overdose of medication. After years of depression and multiple hospitalizations, Eva had died by suicide. She was 42.

“Sharon and I had plans the next day to spend time with friends, another couple, and I guess I thought I could compartmentalize,” Mike says, his voice heavy and halting as he recalls that dreadful day. “I thought, ‘No, let’s not cancel.’ We spent some time at the lake. I remember we washed our cars. It was when I got back to the apartment that it really hit me.”

Mike and his sisters had to sell Eva’s beloved Mustang to pay for her funeral. Back in Lawrence, in the final semester of his senior year, with a job offer from his preferred employer, Conoco, already in his pocket, he found that he could not get out of bed to attend class.

“I thought it was something physical, like mononucleosis, and went to the KU clinic for tests,” he says. “It was a friend who told me, ‘It’s grief.’”

If there was support on campus back then for students trying to battle through such dark distress, Mike did not benefit from its comforts.

“I didn’t seek it,” he says simply. “We are still in the dark ages now, in many ways, when it comes to mental wellness, but we are a lot further along than we were then. Suicide was not talked about. It was in the shadows. I guess it was a matter of shame.”

Close friends knew, and he may have told one professor about his situation. Otherwise, Mike was left to pick up the pieces on his own. He willed himself to finish the semester, collected his diploma, and headed off to start what would become a 37-year career at Conoco.

As the years rolled by, he rarely talked about what became of his mother.

“When we were restoring my Mustang, we’d be working in the garage, and now and then he’d bring up that his mother had owned a Mustang,” Sam McGee says. “He didn’t even know what year it was. I asked him what happened to it, and he just said that after she died the car was sold. In high school, I only had a little piece of the puzzle. It wasn’t until later that I learned the whole story.”

It was Mike’s father who provided the clue that set in motion an annual ritual that lasted 20 years. The car was in Selden, Sam learned from his grandfather, a small town not far from Norton. The same woman whose father had purchased the Mustang for her in 1973 still owned it.

Sam looked her up in the phone book and called. He told her about Eva and offered to buy the car.

That was in May 2001. At the time, Sam says now, the grand plan he eventually developed for the car had not yet formed. “I just had this overwhelming feeling that I needed to bring this car back into the family,” he says. But the owner had no interest in selling.

He asked politely if he could call back in a year, and the owner said yes. The next May he called again and asked to buy the car. And the May after that and the May after that, each year without fail, until 20 years passed. Each time the answer was the same: no sale.

In 2007, Sam laid eyes on the car for the first time, during a trip to Kansas to celebrate his grandfather’s 80th birthday. By then, “getting this car back had become a cause for my wife and me,” Sam recalls. He had learned a lot about the Mustang. Ford had launched a Color of the Month promotion in 1968, and the February color, in celebration of Valentine’s Day, was WT 9036—Passionate Pink. The company manufactured a handful of cars with the striking paint scheme; some were hardtops, some convertibles, and some had vinyl roofs with distinctive patterns. Through his research, Sam determined that only one was made with a vinyl roof emblazoned in houndstooth check: Eva’s. The car was unique. One of one.

The car was rust-free and had only 53,000 miles on it. Seeing it in person, sitting in the driver’s seat and firing up the engine, “kind of ignited my passion,” Sam says. In 2021, attending a family wedding in Colorado, Sam, his wife and kids, and his father drove several hundred miles out of their way to stop in Selden. “It was the first time my father had seen the car since he’d watched his mother drive away in it 50 years before,” Sam says. “So it was a very emotional moment, but I was told again, ‘No, we’re not selling it.’ But I didn’t give up.”

Along the way, Sam came to believe that the car and Eva’s story could be used to raise awareness about the importance of mental health and suicide prevention programs, and to destigmatize suicide and provide support to families who have lost loved ones to it.

He would call the program “You Are One of One.”

Eva Corcoran was beautiful and spirited. And troubled.

Orphaned at 20 months after her mother died and her father remarried and moved away, Eva (along with her sister, Gladys) was raised in western Kansas by an aunt and uncle during the depths of the Dust Bowl. The family, who owned a grocery store in Oberlin, seemed to escape the severest Depression-era hardships, and the sisters enjoyed a relatively comfortable childhood: Studio portraits show two smiling, stylishly dressed girls. The sisters took piano lessons and regularly attended Catholic mass. Eva, deeply religious but also quite rebellious, was said to be a handful. A colorized portrait from her senior year of high school, in 1948, shows a confident, glamorous-looking teen with deep blue eyes and dark brown hair. Friends often compared her to Hollywood icon Elizabeth Taylor.

“She was a beautiful, vivacious woman who suffered from chronic depression most of her adult life and late in life had periods of much more serious mental illness,” Mike McGee recalls. “But when she was herself, when she was on her game, she had a tremendous spark of life. High-voltage smile. Very social. Deeply religious. My mother had a tremendous capacity for love, which she poured into her children. She told me that I could be anything I wanted to be.”

Eva and David McGee eloped the summer after they graduated from Decatur Community High School, taking a train to Denver, where David looked for work. A short time later they returned to Oberlin, establishing a pattern that would continue throughout their troubled marriage. She preferred life in the big city, while he felt more comfortable back home in Oberlin. David’s harsh temper and Eva’s unwillingness to submit to his controlling personality caused frequent conflict. Several years into the marriage, she suffered a nervous breakdown, in the terminology of the times, and sought treatment at a Denver psychiatric hospital, where she was confined for several weeks. It was the first of at least three hospitalizations for recurring depression, which she also treated with medication. The family’s poverty made it difficult to access effective mental health care, and also lessened the opportunities for socializing that the outgoing young mother craved. Shortly after the family moved back to Kansas in 1963, as the marriage continued to deteriorate, Eva left her husband and returned to Denver. Mike, now 13, and his sisters, Kathy and Pat, remained with their father.

Later, after Eva remarried, she asked Mike to join her and her new husband in Denver.

“I took the bus out to visit, and they had all these cool things lined up for us to do,” Mike recalls. “But I’d be leaving my friends; my grandparents were back there (in Kansas). I needed to create my own environment.” Later, as Eva’s health worsened, the demands of completing college while raising a child deepened Mike’s determination to forge a life very different from the one he experienced as a child. The separation from his mother would exacerbate the devastating sense of loss and guilt he felt after she died.

“My shame was, could I have done more to emotionally support her?” Mike says. “Could I have written her more often? Could I have not tried to just save myself, to create my own environment, but instead done more for her?”

That sense of shame and guilt felt by people who lose a family member to suicide is well known to those who work in the mental health field.

“It’s trauma,” says Staci Almager, a Kansas native who lives now in Boerne, Texas, where she is CEO of Hill Country Family Services (HCFS), a nonprofit county crisis organization where Sam McGee serves on the board. “We see it every single day. We are the wealthiest county in the state, a very Norman Rockwell community where it seems like nothing bad ever happens, where everything is perfect. So if you have a child who has mental health issues—or a spouse, or elderly parents—it is very shameful to this day. And what compounds that is, before we started this community coalition, most of the people suffering did so in silence.”

Before Sam even lived in Boerne, town leaders had determined that the greatest community need was access to mental and behavioral health services. “But the bigger issue was how do you even start the conversation?” Almager says. When Sam moved to town and told his story—Eva’s story—“it also helped us tell the story of the greatest needs in our community,” she says.

The uniqueness of Eva’s car seemed to lend itself to the message that every life has value. “This car is a one of one; my grandmother was a one of one,” Sam told the Boerne Star. “When we drive this car around and show it, the message is, ‘You’re a one of one, too.’”

At Boerne’s renowned Weihnachts Christmas parade, at the town’s many car shows and block parties, and during Mustang Club drives and special events hosted by local schools or HCFS, Sam is there—often joined by his wife and kids, who know Eva’s story so well they can tell it themselves.

Large posters produced by HCFS with Eva’s photograph and story help spread the word on the You Are One of One campaign mission: to normalize straight talk about mental health, raise awareness of suicide prevention programs like the national 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, and reduce the stigma of suicide for families who’ve seen loved ones succumb to its ravages.

One purpose unifies those various goals.

“What I think he set out to do is reduce suicide one person at a time,” Almager says. “I really do. But the interesting thing is it has become more than that. The car is a symbol of positive mental health. It is a symbol of the hard conversations you can have because someone understands you. That’s not necessarily what he started out thinking about, but it really is an evolution to what the community needs it to be for them at any one time. It has become more, and he has allowed it to become more, because it needs to be more.”

Almager recalls encountering Sam at a car show, where he was listening to a woman describe her family’s experience of losing someone to suicide. “I’m sure that woman did not set out that day thinking, ‘We’re going to the Boerne car show to talk about my family member who died from suicide,’” she says. “Those are hard conversations because they pull up a lot of emotion. At the same time, it was beautiful walking up on that. When they parted, they hugged like friends. And I remember thinking how unbelievably unexpected and healing for this woman who might’ve felt like no one could understand her experience. But then you go to this random car show and someone really gets you.

“Breaking down those barriers and the isolation and having conversations is very therapeutic for people, and the car helps.Everybody wants to check out the car. The car is cool. It’s old, it’s historic, it’s Pepto Bismol Passionate Pink. We’ve become very comfortable talking about uncomfortable things, thanks to Sam.”

The turning point in Sam’s quest to buy his grandmother’s Mustang came during the 2021 trip when he took his father to see Eva’s Mustang for the first time in a half-century.

On the way back to Texas from the Colorado wedding, the McGees drove several hundred miles out of their way to stop in Selden. By then, Sam had learned all he could about the car’s origins as a special Ford Motor Co. promotion, one of seven Passionate Pink Mustangs made in 1968 and the only one with the distinctive houndstooth top. He’d also started a Facebook group that included the owners of four of the other seven.

Mike remembers the visit as cordial, but one thing was clear to him: “After listening to them talk,” he says, “I was convinced that she’d never sell the car.”

Sam had a different reaction.

“He was pretty composed,” he says of his father’s reaction to seeing the car again, “but it was still a very emotional moment. At that point, I just knew I had to get it back.”

The owner, however, was still not ready to sell. Over the years, she had said no in just about every way you can say it. “Not now.” “Maybe someday.” But she had never said “Never.” So, neither did Sam.

The next year, May 2022, he told the woman that he was thinking of buying a pink ’68 Mustang he’d found in Houston. But he really wanted the car that had actually belonged to his grandmother, the special one-of-a-kind ride that—as Eva had written in a letter to one of her daughters—made her feel good whenever she drove it.

The woman asked for some time to think about it. A few days later, she said yes.

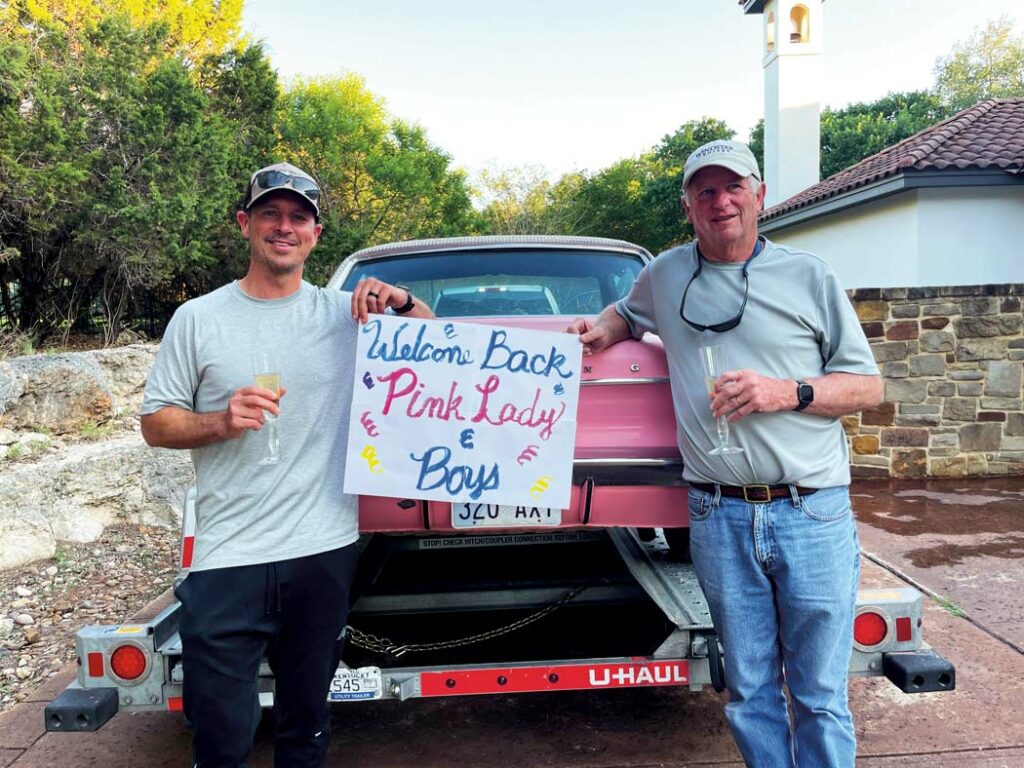

After 20 years of trying, Sam McGee was bringing his grandmother’s Mustang home.

The 800-mile drive from Texas to Kansas to pick up the car turned into “the ultimate father-son road trip,” Sam says. Though Mike had told his family about his mother through the years, he’d mostly focused on the many things he admired about her. Now he was ready to talk about her death. “My father really opened up on the drive, and I think it allowed for some healing,” Sam recalls. “I didn’t know much about the circumstances of my grandmother’s death or how he handled it and what he went through. It’s a long drive from Boerne, Texas, to northwest Kansas, and we talked a lot.

“We went from not talking about it to talking about it, and I realized, ‘Well, that’s sort of the important ingredient for mental health awareness is talking about it.’ You hear about people suffering in silence. So that’s when we decided, you know what? We really need to use this car and Eva’s story for mental health awareness.”

“It was not that we’ve never talked about his grandmother and what she was like or how she died,” Mike says. “I would bring it up sometimes, but we never had really extended conversations about her. He didn’t feel good raising it because he knew it was a very sensitive, painful subject for me. But on that trip back to Kansas, I would tell him everything I could remember about her and everything I knew about her death. It was, by an order of magnitude, the most in-depth, honest conversation I’d ever had with Sam about my mom. So, in that way I think it was really useful.

“Sam and I are close, but I think we came back from that trip feeling closer than we ever have. We’ve done all kinds of things together, but that’s the one that I hold most dear.”

When they rolled into Boerne with the Mustang in tow, Sam’s wife and kids were waiting to celebrate the long-awaited homecoming.

“They had made up posters and there was a banner across the street. They had pink confetti to throw. They made it a big family event,” Mike says.

In a short history of Eva’s life that he compiled around 2013, Mike wrote that not having his children “know and experience the wonderful woman I knew when I was young is the greatest sorrow of my life.”

With the car’s return and the story it helps tell, a missing piece of their family history is now part of their lives, he says.

“Through this car, Sam and his family definitely know who my mom was more than through anything else before. I think that’s wonderful.”

The quest to reclaim Eva’s pink Mustang has changed the way Mike approaches a personal tragedy that had long remained hidden. “I didn’t used to talk about how my mother died. Ever. Now, if it fits into the conversation and I think it can be helpful, I bring it up. It’s no longer in the shadows.”

The McGees hope the effects ripple outward, beyond their family and into their community and the wider world, where mental health is often still underfunded and suicide is still too often seen as a character flaw rather than the tragic outcome of the debilitating disease of depression. Whenever Sam McGee rolls Eva’s ride out of his garage for an appearance at a car show, a mental health rally, or an event promoting the 988 Lifeline and other suicide prevention measures, he’s driving a “rolling tribute” to his grandmother.

He’s also rewriting the ending of her life story, Mike McGee believes. To explain what he means, he goes back to his days on Mount Oread, where he arrived in fall 1969, when a single released by The Beatles the previous summer was still very often on the radio: “Hey Jude.”

“I always liked that song,” Mike says. “There’s a line in there: ‘Take a sad song and make it better.’ That’s what Sam is doing. Eva’s story is a sad story. And what Sam has done is taken that sad song and turned it into something that can help others.”

Rather than a tragic ending obscured by shame and silence, his mother’s life and what she meant to him and the rest of his family now has “a positive side,” Mike says.

Sometimes a car is just a car. And sometimes it’s something more: a haven of safety and solace, an engine for good, a vehicle for escape or connection.

“It’s unique. It made my mother feel good. And then a dad, in his goodness, bought it for the daughter he loved. It meant a lot to her to have that car and know it came from her dad, so in her goodness she kept that car for years and years and years. My son, who knows about my mother and how I feel about her, in his goodness wants to get the car back and eventually does. The woman sees that maybe it will do more good in this way, and in her goodness she agrees. And now the folks in Boerne in their goodness are trying to use it and Eva’s story to help other people.”

Goodness from sadness. Light in darkness. A pink Mustang that’s like no other—as are we all.

If you or someone you know needs help, call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. For more information on You Are One of One, visit youare1of1.org.

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Portraits by Christopher Lee

All other photos courtesy of the McGee family

/