Dissertation leads historian to unexpected post at national park

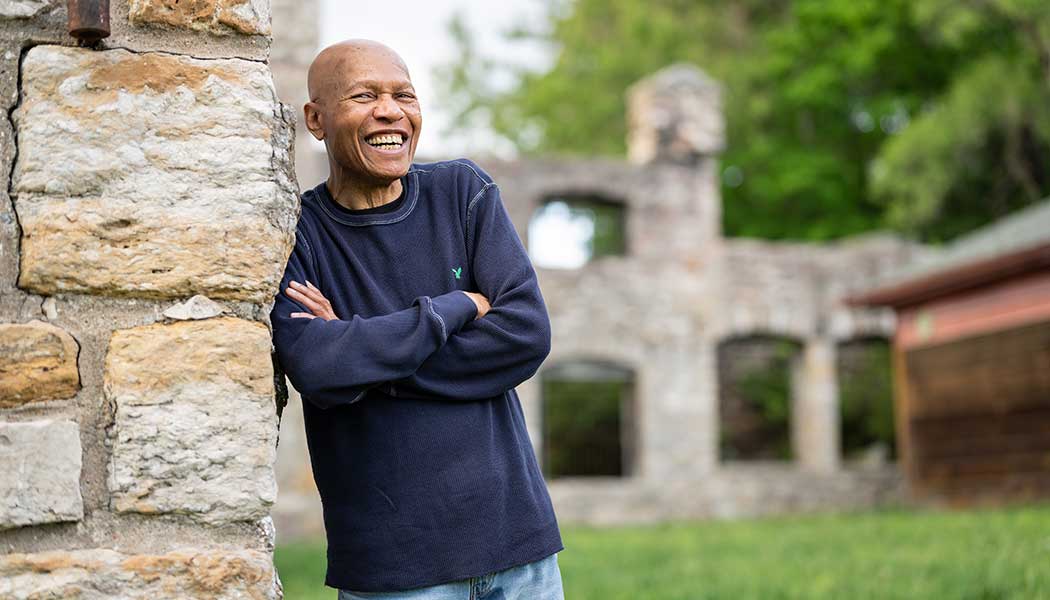

Interpretive ranger Dan Chmill sheds light on African American role in Hot Springs’ famous ‘bathhouse row.’

Through 11 years of higher education, history student Dan Chmill never saw a career working in a national park.

That changed during his time at KU, when he visited Hot Springs National Park and began investigating the history of the African Americans who worked there for decades.

Chmill, a ranger and historian at the central Arkansas park, is teaching others how African Americans helped build and maintain several spas that attracted visitors from all over the world who hoped to find healing in the legendary waters. While working, they helped themselves, their co-workers and their race, too.

“Their story isn’t just that so many African Americans worked at Hot Springs,” says Chmill, PhD’22. “It’s also how so many took advantage of their situation at Hot Springs. They got important jobs, got organized, formed pseudo-unions and really benefited themselves financially. They held a lot of sway in the community and won elected positions.”

Barred for more than eight decades from bathing in the waters where they worked, the African American staff helped end segregation in the park and contributed to the Civil Rights Movement, Chmill says.

The Pennsylvania native first visited Hot Springs National Park in 2018, while working on a doctorate in history at KU. His dissertation, “Taking the Waters: A Hydrological History of Health and Leisure in Hot Springs National Park,” contained a chapter on the role African Americans played in developing and maintaining the region’s famed “bathhouse row.” That chapter turned into the focus of his current career.

A major part of Chmill’s job is a project called “We Bathe the World,” which investigates those roles of African Americans at Hot Springs. His findings are displayed at the park visitor center. He also does speaking engagements and works with the media.

He has collected information from over 1,000 sources, including those who worked at Hot Springs or their descendants, over 250 magazine or newspaper articles, and census reports as far back as 1870.

Chmill’s research and presentations are especially appreciated by local African Americans.

“We have an African proverb that says, ‘When an old man dies, a library burns,’” says Marsalis Weatherspoon, president of the Hot Springs branch of the NAACP.

“A lot of us grew up hearing the stories, but having Dr. Chmill go to such lengths researching it and making it so available to the public is so very important. It’s taken time to get this kind of important information out there. Whenever it comes, we’re so very grateful.”

Chmill credits KU for helping develop his passion for the subject.

“Time with Shawn Alexander (professor and chair of KU’s African and African-American studies department) really encouraged me to start digging deep into the history of race and the environment,” Chmill says. “There are so many stories here to be told.”

For centuries Native Americans came to the valley with 47 individual hot springs, which have an average surface temperature of 140 degrees. In 1832 the U.S. government designated the region a national reservation to help protect the springs, which were thought to have medicinal powers.

After the Civil War, the region saw tremendous growth as railroads came to the area. People from all over the nation visited for stays of three weeks or more, hoping to heal assorted ailments at “bathhouse row,” which included eight different bathhouses in what would officially become a national park in 1921.

The bathhouse industry boomed in the 1880s and attracted African Americans searching for jobs. Workers included both those who’d once been enslaved and those from the North whose families had been free for generations.

Jobs at the bathhouses often required specialized training to follow doctors’ orders for bathing guests, wrapping them in wet towels and giving specific massages, Chmill says. By 1900 many workers had incomes that placed them in a growing African American middle class. The pay allowed many to travel and secure good medical care, rarities in many African American communities.

Barred from park waters by segregation, African Americans built their own bathhouses a quarter-mile away. Some of the nation’s most prominent African Americans came to those bathhouses, which became a popular meeting place as the Civil Rights Movement unfolded in America.

A 1963 “bathe-in” by prominent African American leaders at a whites-only bathhouse drew national attention and led to successful talks to end segregation at the park. By then, Chmill says, attendance was declining.

“It really started to go down after World War II. People could get an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory pill. They no longer needed to dedicate three weeks at a bathhouse to feel better.”

Today two bathhouses at Hot Springs National Park cater to tourists, who may spend just a day or two at the springs. It’s hoped they also spend time in the visitor center, learning from Chmill’s research.

“These people served their park, they served their community, and they served each other well. What they did was important in so many ways,” he says. “People need to know about them.”

Michael Pearce, ’81, a Lawrence freelance writer, is a frequent contributor to Kansas Alumni.

Photo courtesy of Dan Chmill

/