‘Controlled chaos’: Inside KU professor Marshall Maude’s ceramics

Issue 4, 2024

Draw near, friends, and let us noodle around with some stereotyping. So often it’s the unsupported and potentially offensive observation that peppers up a drab pot of storytelling, and rarely does it turn out badly, right? So it is, with apologies, that one might have expected interest in Marshall Maude’s Oct. 10 artist talk for his solo exhibition at the Lawrence Arts Center, “The Sun and the Moon,” to run low.

Not for the art or artist, but, heck, the first pitch of Game 4 of the American League Division Series—a savory renewal of the Yankees-Royals playoff slugfests of old that turned many of us into baseball fans, and Yankee haters, for life—was set for the exact same time. After three games decided by a total of four runs, the Royals trailed two games to one, needing a win to advance to a decisive Game 5. So who, exactly, would bother showing up for an art talk? And how clueless could an artist—arteeest?—be, pitting a ceramics lecture against the Royals’ do-or-die playoff game?

Mere minutes before the event began, few art fans had yet to show up. If he even noticed, Maude didn’t comment on it—did he even grasp why this whole thing was such a terrible idea?—and even someone irritated at missing the game might have felt bad for the guy, having to stand before an empty room and talk art while the big game was played on innumerable TVs in a dozen crowded bars within blocks of the New Hampshire Street art exhibition.

But no, Maude just carried on with his preparations while politely indulging a few early questions about the assembled pieces.

“Ceramics,” he explains, “is all about timing,” and resistance to the idea of spending the next 90 minutes in his company, and not Bobby Witt Jr.’s, begins to peel away. He explains about how clay shrinks, and shares some of his thoughts on “the making process,” and seemingly as if by magic, his audience has arrived and assembled, filling nearly every seat.

“Well, we’re missing Game 4,” Maude whispers, “so we’d better make it good, right?” OK, that was unexpected. “But maybe,” he continues, “we can all party on Saturday.”

An artist who knows that, should the Royals win, the series would end the day after tomorrow? Yep, we’re all in. Come, then, let us discuss art, ceramics, creativity, dualities of life and death, sun and moon, Royals and Yankees be damned.

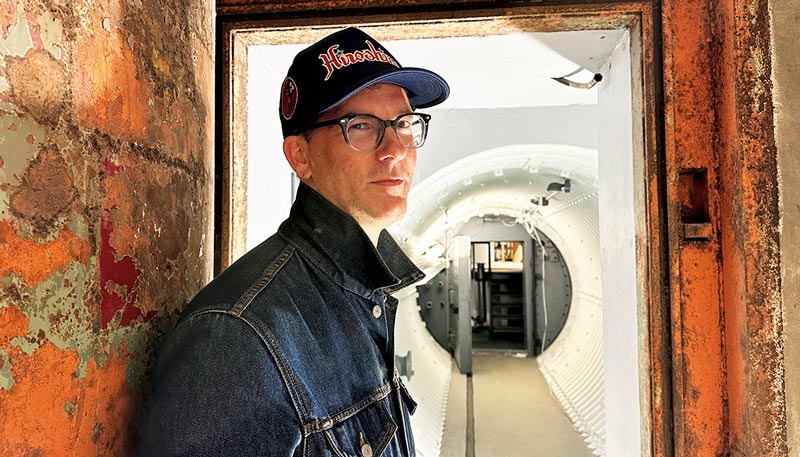

Marshall Maude, f’96, g’03, is an associate professor and chairperson of KU’s department of visual art. He is an internationally recognized ceramic artist who specializes in firing his work in 2,400-degree wood kilns, a chaotic, organic process completely different from predictable firings in electric or gas ovens. Compared with the dynamic environments of wood kilns, graduate student Meredith Smith explains, firing in electric kilns is akin to “programming what is basically a big toaster and walking away.”

Maude is a man on the move. Always. Reached on his phone during fall break—a time when students and faculty are supposed to rest and recuperate ahead of the mad dash toward semester’s end—Maude explains that he’s having “a little bit of a studio day,” and the thought occurs: Does an artist get time off? Can the creative process ever reach full stop? “That’s one of the positives and negatives about it,” he replies. “For sure you can’t take a day off, and you can never retire.”

Maude somewhat reluctantly accepted the administrative load of department chair following Tanya Hartman’s 2021 departure for Michigan State University. He honored what he saw as a service obligation to the department where he’d earned both of his degrees and had established his professional home, but also because he already had significant projects in mind.

“It’s a little easier to enact change from the top,” Maude says, “but I don’t really have any ambition to be in any kind of administrative leadership role. I mean, I literally have no ambition for that. Basically, nobody else wanted to do it, and I was sort of willing, and I think most people would agree there’s some element of service that needs to be taken on.”

Graduate director Sarah Gross, associate professor of ceramics, says that as a “small program in a large research university,” it was important that Maude embrace the department’s traditional strength as “a setting that isn’t cutthroat. … It’s a competitive program to get into, but we try to create an atmosphere that is comfortable and warm, and not about outdoing everybody or making other people look bad with your own successes. It’s more about lifting each other up.”

Maude last year realized a dream project by creating gallery space for students in East Lawrence, in what had been a popular houseplant store, and he’s currently enmeshed in plans to move KU’s photography program from its current home in the School of Architecture & Design into the visual art department within the School of the Arts, a transition set for fall 2025.

And, reclaiming what had been a facilities maintenance shed bordering Bob Billings Parkway, on West Campus, Maude created what he calls the Interdisciplinary Ceramics Research Center (ICRC), welcoming both international ceramic artists and KU faculty interested in exploring ceramics for their own research.

“He puts his money where his mouth is. He takes risks,” Gross says. “The ICRC is his brainchild. We’ve had all these wonderful, yearlong artists-in-residence come and teach and work and exhibit, based on this space, and we have studio spaces there where grad students and faculty can work. That was all something that that came out of his brain, but also his blood, sweat and tears. The same with the new downtown student art gallery.

“It’s such a great idea, and not only does he have the vision to think about it, but he has the sort of connections to the community to actually find a place to make it happen. And then he has the construction skills to completely renovate the old Jungle House and turn it into this cool gallery space that gives students a chance to put their work out in our community.”

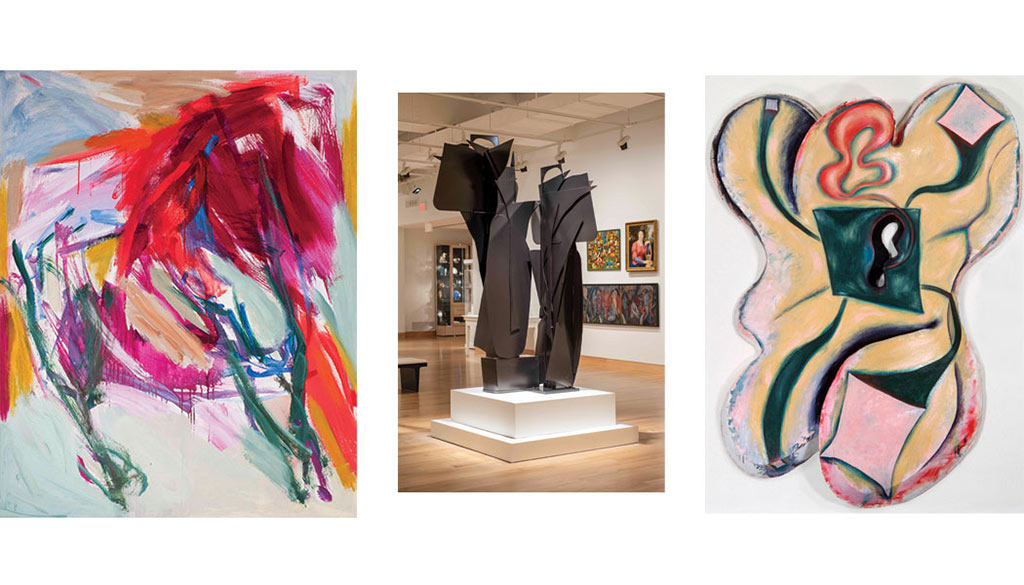

Ben Ahlvers, the Lawrence Arts Center’s exhibitions director, says he and Maude, friends and colleagues of many years, began discussing this fall’s show 18 months ago. Yet as well-versed as he is in Maude’s concepts, even Ahlvers, intrigued by laser-cut etchings imposed on diamond-hard glazed surfaces, had questions about his techniques.

“It’s an interesting combination of technologies, with firing, a process that’s hundreds if not thousands of years old, and then laser etching,” Ahlvers says. “The principle isn’t revelatory. People have been advancing and combining things since the beginning of time. But I don’t know of anybody else that’s doing it quite the way he does. I think putting a hard line on that surface is a deliberate touch that echoes everything he talks about. At almost every step in the process, the dualities ring true, and they’re universal.”

As Maude prepared for his talk, he decided to experiment with the format. Rather than save questions for the end, when a few truncated answers are typically shoved into a five-minute window, he dedicated the entire hour and a half to answering questions, which touched on the full array of works on display: imposing black vessels, glimmering with coats of graphite and India ink, occupying the center of the room; collections of copper-glazed, wall-mounted pieces, their variety of dazzling colors created entirely by the firing process; and an intriguing time-lapse video of a clay vessel perched in a river, to be viewed through a ceramic frame hanging a few feet away.

“What I’ve been thinking about when I approached the work in this show,” Maude says, “was the idea of dualities. The meanings are relatively layered, I guess, and complex, but the forms are pretty simple. I was thinking about relationships. Some of the grounding principles behind all this are ceramic history, art history, and, I would say, nature, and permanence or impermanence, whichever way you want to go.

“I started thinking about the idea of impermanence and permanence being the same thing, basically, so, with that duality, the title of the show is ‘The Sun and the Moon.’ I don’t think I wanted to call it ‘Life and Death,’ but it could have been that.”

Duality—the state of having two different or opposite elements—is the ideal concept for Maude to work through in his creative output, because it seems to capture his own ways of being, thinking, doing.

“He’s casual and charismatic,” Ahlvers says, “but he’s also really intelligent, and he’s very thoughtful about what he’s doing. He and his ideas are very approachable.”

Gross offers additional examples. “His work is well respected, but he’s also not somebody who’s promoting himself,” she says. “He’s not constantly out there, posting to his online followers, ‘This is what I’m working on!’ There’s this sort of absence of ego that I’m pretty jealous of. There’s just something about him that’s, like, unburdened and irreverent. That lack of ego. Like, it just doesn’t even occur to him to worry, you know?”

Maude grew up in Topeka, and credits his mother, a graphic designer, and “really great” art teachers at Shawnee Heights High School for his development as an artist, although he also recalls an innate interest that announced itself when he was 5, digging around in clay on a lakeshore behind his grandparents’ home.

“I remember making pots and drying them out and then sticking them back in the water and letting them fall apart,” Maude says. “There’s some sort of serendipity that sometimes happens in life where it’s like … I don’t know that it was somehow a memory that caused that …”

In his unbounded, meandering manner, Maude seems to be referencing the video installment in his arts center show, “Re:claim,” featuring a time-lapse video of an unglazed vessel. As he told the audience and later discussed in detail, Maude created the vessel in situ, digging into clay near the bank of the Verde River in Arizona. He placed it in the tributary’s small stream and, relying more on intuition than actual skill, filmed 24 hours of the vessel’s brief existence.

“I guess my entry point into clay was the vessel, right? That’s pretty common with young people,” he says. “They take a class, or they see somebody throwing pots on the potter’s wheel, where you can take this amorphous lump and transform it into an object, and there’s seemingly magic involved with that, right?

“In 2017, I made an intentional shift in my focus to reinvestigate the vessel, a signifier of our culture, a signifier of humans, or even the signifier of self. Food storage, grain storage, water storage, these foundational principles, these fundamental elements of humanity. We couldn’t exist in our current state if we didn’t have these things, right?”

Although “Re:claim” perhaps reflects Maude’s earliest experience with clay dug out of a watery bank, the connection to his past was completed after he shot the video, as upriver rains suddenly swept through and the swelling Verde reclaimed its own, exactly as Lake Quivira had done with his first artistic output.

Maude admits that his nascent videography skills failed him at that moment, and he did not capture footage of the pot dissolving back into river clay. Yet he also hints that he’s happy that he simply watched it happen, without technology interrupting his reverie.

“I have a lot to learn, and I want to go into any project without knowing what the outcome is going to be,” he says. “I don’t really, particularly, have any kind of point. Like, I’m not advocating anything, right? I’m not trying to push an idea or an agenda. I’m just sort of looking. I’m interested in certain things, so it’s just a way to sort of ask questions and sort of think about things.”

The artist’s mindset, Maude has discovered, happens to blend beautifully with the rigors demanded of an educator, a concept he embraced while complying with KU requirements that “specific learning outcomes” be delineated in every syllabus.

“Sometimes that sort of system is a little bit difficult to wrap your mind around, right? I would think that in some sort of math class or something, it might be a little bit more straightforward, but in an art class, the learning outcomes are not always super clear. Or, they seemingly might not be.”

The solution Maude hit upon is, like his art, elegantly simple and deeply thoughtful:

- Build skills that translate to confidence in decision-making.

- Trust your instincts.

- Understand failure as a component of success.

- Develop patience and an acceptance of loss.

“I’m not sure that’s what the provost had in mind when they asked us to do that,” Maude says, laughing, “but I tell my students, ‘This can potentially be the most important class you’ll have, because there’s a lot of failure involved with ceramics, right? Just like learning to play the piano, it’s a skill to learn how to manipulate clay. You’re going to have to go through a process to learn that skill, and one of the things that you can learn is patience, and that there’s a lot of loss involved. Especially with the ceramics world, there’s failure in every stage.

“So, for patience and the acceptance of loss, I tell my students, ‘If you can learn those two things, your life will be a lot better.”

One of the joys of the study and practice of ceramics, Maude and Gross agree, is that dirty hands discourage the use of cellphones. When students are in their twice-weekly three-hour classes and the mandatory six hours of studio time, they are loosed of their modern distractions and free, finally, to focus.

Given how proud he is of his department’s embrace of technology—including a computer numerical control (CNC) router, laser cutters, vinyl cutters, machines that make digital screenprints and ceramic decals, and digital drawing tablets—Maude concedes, but won’t apologize for, hypocrisy in his art form’s eternal fascination with the basics of clay, water and fire.

“There are no phone rules,” he says of classes. “Then I just turn into a weird policeman or whatever. But just the very nature of the process is engaging. It’s physically and mentally engaging. Our students all pretty much cut themselves off from their phones, and I’ve had a lot of students tell me about how that’s really important for them and how much they appreciate it.”

On a recent Friday morning, KU ceramics students and local artists from the Lawrence Arts Center gathered at the Chamney Barn Complex on West Campus to chop donated wood in preparation for the November firing of the beastly anagama kiln, the largest of five kilns housed within the covered, open-walled space, every inch of it built and maintained with private funds donated through KU Endowment. This year’s event was the 15th renewal of a KU-LAC collaboration that unites the vibrant regional ceramics community in a celebration of transforming clay and glaze within the “controlled chaos,” by Ahlvers’ description, of turbulent tubes filled with deep beds of embers and swirling ash.

Climbing out of his 1998 Toyota T100 pickup truck, Maude offers visitors a tour, taking particular joy in pointing out the “pizza kiln,” where, you guessed it, tasty eats are baked during the four days required to fire the big anagama—“There’s people out here 24 hours a day,” he says, “so you might as well make it a fun little time”—and just as quickly he’s over by the woodpile, firing up a very serious chain saw, a gnashing brute that appears to exist somewhere between dad’s backyard trimmer and a lumberjack’s pro model.

“Students really value the space and opportunity that they get with ceramics classes,” Gross says, “especially doing those wood firings where they’re outdoors, working, doing physical labor with their bodies, chopping and stacking wood. And more and more, students are interested in digging their own clay, finding local clay and testing it, processing it, even learning chemistry to adjust the clays.

“The University is often trying to encourage other faculty to do what we are always doing: engaged, hands-on learning.”

To Maude’s fast-paced, fast-firing mind, the educational process comes down to basics as simple and pure as clay, fire, ash: conceptualize, create, repeat.

“Take the thoughts that you have in your mind and the skills that you have in your hands and blend them into some kind of thing, whether it be an object or an expression or whatever it is,” Maude advises. “Those are skills that can actually be learned, and it’s the same thing I’m doing in my studio. For me, teaching and working in my studio are not too dissimilar, in a lot of ways.”

“You know, there’s no one type of artist. I mean, even though everybody probably has some kind of stereotype of what an artist is, that doesn’t really … that’s not really … there’s no truth there, right?”

The whole ballgame, stereotyping be damned. And the Yankees, too.

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photos by Steve Puppe

/