Plot twist: Retired professor writes a second act

Issue 1, 2023

Sheriff Billy Spire is so physically unattractive that his face startles people, including the troop of girls from Garden City, Kansas, 20 miles to the west, who found the unattached hand on the bank of a roadside stream. The sheriff is steady and tough, competent and fair. A former football star and Marine with axe-handle shoulders, Sheriff Spire doesn’t start fights—at least not since a cheap hit during a high school football game that haunts him still—but he can and does end them, though rarely now with his fists, thanks less to his badge than a stony glare that few dare challenge.

Billy Spire knows how the world sees him—the world, in his case, being the citizens of Ewing County, who have kept him at his post for 12 years. He carries 240 brutish pounds on his 48-year-old, 5-foot-9 frame, the picture of rugged, rural masculinity, a true man’s man. Yet before he exits the cab of his silver Dodge Ram 1500, the sheriff forces himself to breathe steadily while repeating his mantra:

“The first pulse to take is your own.”

He has arrived at a crime scene and needs to make certain he projects confidence and competence. There is a mystery to solve, but let’s be calm about it. No sense in anyone getting ruffled or rushed.

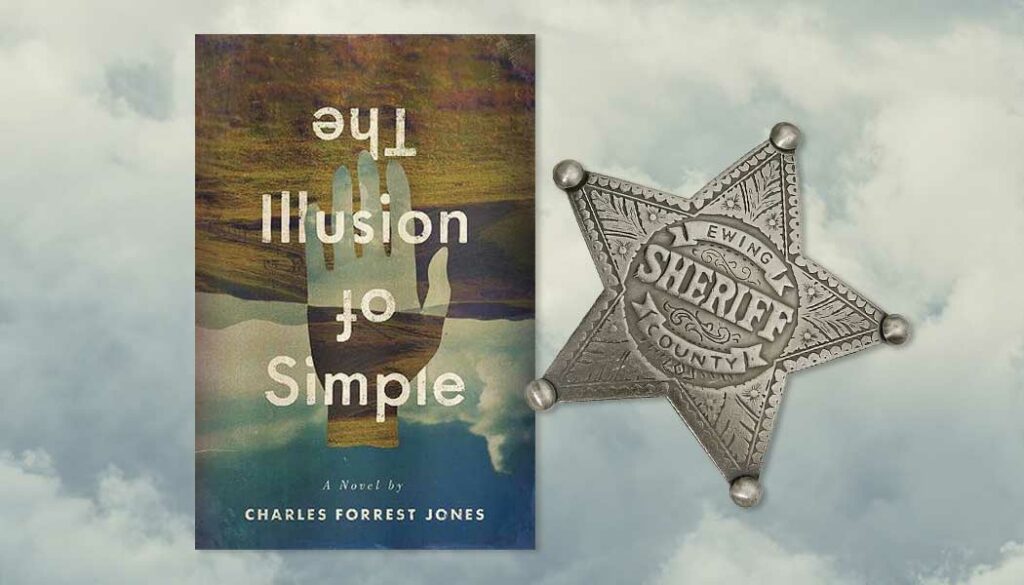

Good thing, too, because Sheriff Billy Spire won’t solve the mystery of the unattached hand for more than 30 years. Not for laziness, but because he does not exist. Nor does Ewing County, nor his constituents, nor the girls who found the hand or the trucker they first flagged down for help. Until the 2022 publication of The Illusion of Simple, they existed only in the mind of a storyteller who at the time was devoting his writing skills to explaining complex water issues to worried and sometimes annoyed Kansans, and later teaching those communication skills to his KU public administration students.

Thankfully for the rest of us, Charles Forrest Jones never forgot about Billy Spire. After his retirement in 2014, Jones, c’79, sat down at his computer, opened a fresh document and set about learning more about life in Ewing County, Kansas, population 1,232, nearly all of it in Stonewall, the county seat, where there’s a farm equipment dealer, an independent telephone company, a rural electric cooperative, a grain elevator, a bank, a mechanic’s garage, a liquor store, the Gas-N-Go, Effie’s Diner and a half-dozen churches—only enough “to sustain that which has endured.”

We each carry with us the vision of a perfect retirement. Travel, perhaps. Tending the tidiest lawn in the neighborhood. Woodworking in the basement. Golf. Painting. Sculpture class at the community arts center. Yoga. Pickleball. Grandkids. Middle-of-the-day margaritas.

For Charles Jones, retirement as director of KU’s Public Management Center and courtesy associate professor in the School of Public Affairs and Administration was less about writing the Great American Novel than it was a long-overdue chance to spend quality time with his wife, Carol, c’68, g’70, l’79—a noted quilter who had retired as a research attorney for the Kansas Supreme Court—at their second home in Creede, Colorado.

He also viewed retirement as the perfect opportunity to step aside and make way for others in the profession he adored.

“I felt like I got a lot of great things done, and I was very proud of my work,” Jones says. “But then it’s somebody else’s turn. Somebody else brings new energy, new vision, new possibilities.”

And, yes, there remained the unfinished business of Sheriff Billy Spire and the mysterious hand, a story to which he yearned to return, but writing wouldn’t be something Jones would pick back up.

He’d been writing all along.

“All through my career, the fact that I wrote well was a source of real pride, but, more importantly, real power to me,” Jones says. “Any organization has limited resources. And so whether you’re talking about wanting money from the budget, or if you want to advance a policy idea or you want to develop a new program, you face a great deal of competition among everybody else who wants to do those things. If it [a proposal] is well written in a way that has a human face, it gives you an advantage in that competition.”

Growing up in a troubled family dogged by a grandfather’s unfortunate business scandal in New Mexico, Jones moved 18 times before he was 18 years old and changed schools 12 times. He recalls being, understandably, “not a very good student,” and with only a stint at a Los Angeles community college to show for a halfhearted effort at higher education, Jones was 27 when he arrived in Lawrence, at the suggestion of a friend, and enrolled at KU as a pre-med biology major.

“There are lots of things that could have taken me the other way. I’m lucky,” Jones says. “I was very, very fortunate to find people who could see things in me that I couldn’t see in myself.”

His intention to become a doctor was, in retrospect, less than sincere; rather than hoping to tend to sick people in their times of need, Jones saw it as “a good job to have.” A rough semester packed with physics, chemistry and population statistics changed his mind, but Mount Oread’s magic had already cast its spell: He’d entered a campus poetry contest and, to his still undimmed delight, took third place: “Not bad for a biology major.”

Buoyed by his bronze medal, Jones sought out creative writing for an elective course. In another fateful turn, he fell in with Professor Floyd Horowitz and soon became a regular at Friday night dinners hosted by the English department titan and his wife, legendary KU administrator Frances Horowitz, then vice chancellor for research and graduate studies.

“I think the thing about Chuck is, he listens,” says the Horowitzes’ son, Benjamin Levi, now a philosopher, bioethicist and pediatrician in Hershey, Pennsylvania, who has maintained his friendship with Jones. “He has a fascination with people, and a sympathy for people who are down and out, although I don’t think he’d characterize them in that way. They might even see themselves as down and out, but Chuck looks to see what else is going on there.”

With his biology degree and a blossoming interest in writing, Jones landed a job at the Kansas Corporation Commission, the state’s utilities regulator. When his employer won a grant to host a conference on energy conservation, talk turned to how best to promote it. Jones decided he had little to lose, so he spoke up, suggesting they land a big-name movie star to tape a public service announcement.

“Everybody laughed and said, ‘Yeah, well good luck with that. Give it a try.’ And maybe three months later I was in the radio station in Topeka and we were talking with Gregory Peck on the telephone.”

The idea, Jones concedes, was “naïve and simple,” but it worked. Jones found a reference book with contact information for Hollywood agents whose famous clients, Jones hoped, might be inclined toward environmental awareness. He wrote a one-minute script and sent it off. Paul Newman did not respond. Gregory Peck did.

Suddenly a somebody around the office, Jones was asked by Pete Loux, the commission’s chairman, to write speeches. “Once you’re writing speeches, you begin to say, ‘Well, why would you do this?’ and ‘why would you do that?’” Jones explains. “That put me into the line of policy analysis, which is what I pretty much did throughout the rest of my public career.”

During a change of administration in the statehouse, Jones decided it was time to move on. A friend in Boston suggested he consider graduate work at Harvard University.

“I just rolled my eyes and said, ‘Sure.’ He said, ‘Well, you could try,’ and I said, ‘OK, I’ll try,’ and I got accepted.”

Like Jones, Harvard classmate Elisa Speranza worked as a communicator for large public-service agencies, specializing in water-related critical infrastructure. She, too, dreamed of doing more with her writing, and published her first novel, The Italian Prisoner, in April 2022, just months before Jones published The Illusion of Simple.

“Charles is a very sensitive guy, a very empathetic kind of person,” Speranza says from her home in New Orleans, the setting for her World War II-era story of unlikely love. “He’s a very deep guy, in a great way. He’s a lot of fun, too, but he’s very thoughtful.”

Forging lifelong personal and career connections with colleagues such as Speranza was, Jones says, one of the primary benefits of earning a degree from the Kennedy School of Government’s mid-career master’s of public administration program. The other was discovering that he belonged in their lofty company.

“I learned I can run with the fast horses,” he says. “I did fine. I did really well. And it gave me a much greater sense of intellectual competence than I’d had before.”

Jones followed his Harvard sojourn with work in private-sector environmental consulting firms, and in 1991 he was named director of the division of the environment at the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. His four-year tenure took Jones to every corner of the state, meeting with constituents in good times and bad. He learned, for instance, that a leaking underground storage tank that drives a mom-and-pop gas station out of business can gut the economic health of an already-struggling tiny town.

Jones became more aware than ever of the importance of effective communication, figuring out how to explain complex scientific topics in the sweet spot between obfuscation and pandering, lessons Jones carried with him when he successfully ran for the Douglas County Commission in 1999 and joined the faculty in KU’s nationally acclaimed public administration program in 2003.

As he compiled reading lists for his students, Jones added seemingly unlikely choices for future government and nonprofit administrators: Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft; The Glass Castle, by Jeannette Walls; and Man’s Search for Meaning, by Viktor Frankl.

Within the context of their own career interests, Jones assured his students, effective writing is the surest path toward gaining attention. It’s also the only way to communicate the complex issues of their trade with the citizens they’ll need to win over.

Jones says he learned the concept of “bounded rationality” from another of his KU mentors, Distinguished Professor H. George Frederickson, and it became central to his career: People are rational within the limits of their ability and time to understand a concept. Once a topic exceeds their bounds, they tend to fall back on self-defining fundamentals, which ends productive discussion.

It’s a timeworn opposition strategy that can sink even the most well-positioned arguments: Keep pushing for ever-growing complexity, and eventually the audience stops engaging.

“That’s why it’s important for public servants—who I still believe are kind of on the side of the angels—to make sure that they stay within rational bounds to be effective,” Jones says, “and don’t let themselves get sucked into a technical discussion that people roll their eyes and walk away from.”

Good governance, it turns out, is much the same as selling that long-dreamt-of first novel: Good writing carries the day.

“Write a really good book. That’s step one,” Isabelle Bleecker, a founding agent at Nordlyset Literary Agency, based in New York’s Hudson River Valley, advises unpublished authors seeking to crack the code. It worked for Jones, whose pitch rose from her slush pile in part because Jones followed the rules—do not include attachments in any unsolicited emails!—but mostly for his manuscript’s insightful journey into a part of the world known to few outsiders, including urban Kansans. Bleecker landed The Illusion of Simple with University of Iowa Press, which is fastidious in curating a limited fiction catalog that reflects well on the school’s vaunted reputation for creative writing programs.

“I loved the hook, with that mystery starting out,” Bleecker says. “But then you realize that it’s also a masterful look at the human condition, with complex, carefully drawn characters, and just a beautiful look at complexity and compromise and politics. It was so much a book of the times because he really didn’t shy away from looking at racial and economic tensions.”

After Sheriff Billy Spire encounters the unattached hand, The Illusion of Simple explores generations of life in small-town Kansas, evoking flavors depicted by Kent Haruf, ’68, the late, great novelist of Colorado’s High Plains. Observations on people and place slip into the narrative page after page. All we need to know about the local mechanic, Leo Ace, is that he’s “never had an unspoken thought.” Billy’s father, Joe, taught his son “a capacity for rage,” and a radio playing inside an empty shed signals to Billy “the queer space of unexpected death.”

When Billy falls in love with a roadhouse beauty and proposes marriage, Nadine doesn’t say yes, doesn’t say no, only that she won’t stop drinking for him. He tells her she’s beautiful, to which Nadine replies, “And you’re a fool.” By which she means not to mock, but only to point out what she saw as obvious: Billy was taking on more than he knew, and would not be the better for it.

“She can see in him the things he can’t see in himself,” Jones says, “and, in her own broken way, she’s there’s for him.”

Nadine sees in Billy the strength of character he can’t see in himself. It is the storyteller’s story, the good fortune that carried Charles Forrest Jones from an itinerant life in California to life-changing experiences at KU and Harvard, through his multifaceted career as public servant and devoted teacher, and, finally, as a novelist with plenty to say about his adopted home state.

Peering down from 30,000 feet, coastal travelers sick with the affluenza of the upwardly mobile might scan a tableau of serene villages and geometrically tidy pivot-irrigated fields. It is an illusion of simple, and even Kansans who live far from the farms and feedlots that sustain us commit similar sins of dismissiveness, kidding ourselves into thinking we know something about small-town life by visiting quaint Main Street cafes for a slow-paced Sunday breakfast.

“And so the whole point of the book,” Jones says, “was to expose the myth of simpleness. What’s happening in western Kansas right now is complex, difficult and hard. There are populations being displaced, and some of those displaced populations are going to turn to malevolent causes.

“All I can say to you is, I love those people. I had to know what was going to happen to them.”

It wasn’t until retirement that Jones could finally see it through, but see it through he did. He even has a second book already with his agent, which he describes as a departure from the complex tale that unfolds within The Illusion of Simple.

“It was something that I yearned to do, and I looked forward to doing in retirement,” Jones says of retrieving his early notes about a character called Billy Spire. “And then when I did retire, I found it even more necessary than a luxury, because, you know, I want to have some purpose to my life. I wanted to be doing something. I wanted to be working on something. I didn’t want to sit around bored.

“So, writing has become not just a luxury, but, yes, it gives my life its meaning right now.”

The first pulse to take, said the man wiser than he knows, is your own.

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photos by Steve Puppe

/