The unlikeliest Jayhawk: Ukraine’s U.N. Ambassador Sergiy Kyslytsya

Issue 1, 2025

The man serves as Ukraine’s ambassador to the United Nations, where Russia—a country waging a savage war dedicated to the destruction of his homeland—still enjoys a treasured seat on the all-powerful Security Council, a status it inherited amid the ashes of its forebear, the Soviet Union. So please let us grant that, a) Sergiy Kyslytsya shoulders one of the world’s most difficult jobs, and b) is a world-class diplomat, which by definition demands absolute precision in language and word choice.

And so it was that, twice in as many days during his November visit to KU and Lawrence, we found ourselves mulling Ambassador Kyslytsya’s description of our homeland as “banal.” He seemingly grasped that we could take offense, because, flashing a sly, gotcha grin, he quickly expanded on his line of thought: Americans, he said, especially Kansans and other Midwesterners, “can know philosophy or ancient history better than many Europeans, but even those people would like to talk to you in a very simple way. They don’t like hidden agenda. They don’t really like to guess what is your position.”

Rather than using “banal” to describe a lack of creativity or originality, Kyslytsya enjoys the word’s implication for straightforward speech and manner, often lacking among his international colleagues. Kyslytsya embraces straight talk, and he says his heartland experience is one of his strengths when working within the diplomatic enclaves of New York, Washington, D.C., or Brussels, or the monetary and cultural strongholds of Los Angeles, San Francisco or London.

His advantage, as Kyslytsya sees it, is Kansas. Specifically, his academically rigorous sojourn on Mount Oread during the 1992-’93 school year, as an exchange student late in his college career.

“One of the things I’ve been telling my colleagues and my leaders, my bosses, before I became a boss myself, was that, in my opinion, American people are banal. But, that banality is a sincere ability to trust, and people in this country trust you—until you lie to them, you know?”

In other words, the ambassador explains, to know America, one must first know the Midwest—life lessons shared by few others in his circles of power. His sincere affection for Kansas and his pride in being a Jayhawk are aspects of his personal history that he does nothing to hide. They are, in fact, bragging points in life-and-death pursuits of the very highest consequences.

“I have always kept Kansas in my mind, believe me,” the ambassador says during a light lunch of sandwiches and sodas in the Jayhawk Welcome Center’s Joseph C. Courtright Pub. “It is not because you are from Kansas, or because I am in Kansas, that I say this, but because I was so blessed that I got this kind of vaccination, immunization, this injection of the American heartland experience at a very early age.

“Because of that, I could relate to many things, unlike many people around me who never studied in the United States, or even those who had the best education from European universities. They should all travel to Midwest.”

KU and the Alumni Association officially view former students who successfully complete at least one full semester as alumni, regardless of degree completion—status unknown to Sergiy Kyslytsya when he left KU in a rush because he was needed back home. As Ukraine reassembled itself after shaking off the yoke of Soviet-style communism, jobs were filling fast, and, from the time he could walk and talk, Kyslytsya had only one dream.

“I knew from a very early age that I want to be a diplomat,” he says, “because I like the world. I like to explore the world.”

Although he found comfort in the rural, agricultural and proudly self-reliant character shared among Ukrainians and Kansans, the ambassador is quick to note that he was never a farmer.

“My parents were very urban people,” he says, almost sharply, as if for emphasis. “They lived in the capital all their lives, and for generations.”

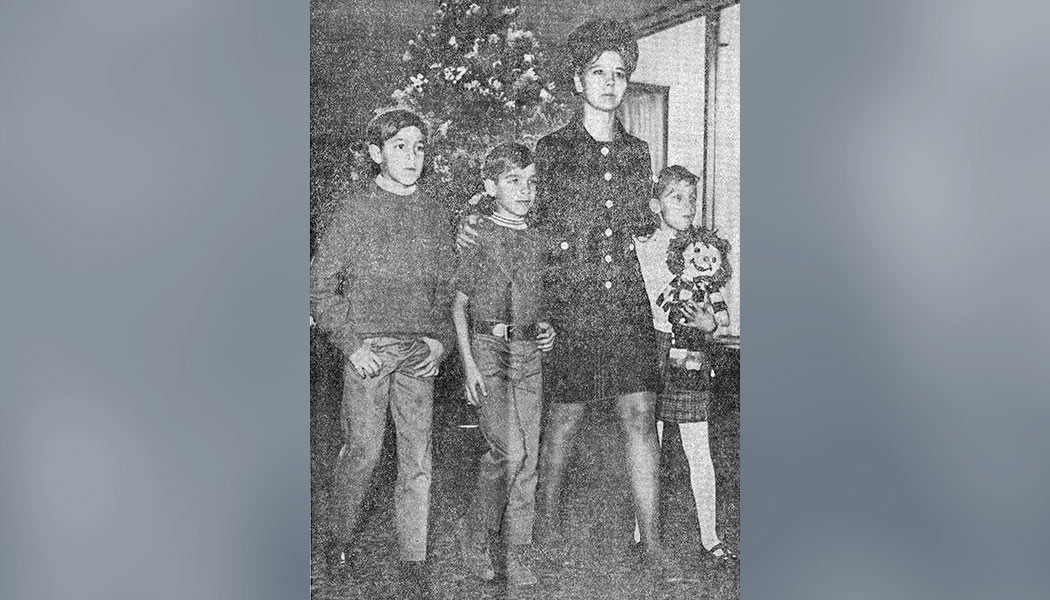

Despite pervasive travel and educational restrictions placed upon citizens of Eastern Bloc countries, his parents taught him English—“I was speaking my version of English before I even started to read or write,” he says—along with French and German, and he has since added Spanish. “Even during the Soviet times, with this kind of wall around the Soviet Union, there were still ways to receive information in foreign languages.” His family’s insistence on rigorous education served a specific purpose, as children were expected to leave home early in pursuit of both higher education and self-reliant adventure.

“In my family, it is a century-long tradition that children should be independent very early,” Kyslytsya says. “I left my family when I was 16. My son left our family when he was 16. You have to get a very good education, and then you have to go, but if you go to a college, then family supports you.”

Kyslytsya was in his early 20s, and the Soviet Union was on the brink of collapse, when he applied for a prestigious opportunity to attend an American university—with KU as one of the participating schools—as an exchange student. The name of the program has been lost to time, yet it was prominent enough that he had to travel to Moscow for an interview.

“In the final year or two of the Soviet Union,” explains Erik Scott, John P. Black Professor of History and director of KU’s Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies (CREES), “they created what was like a Soviet Fulbright program, where they had this competition across the whole country. It had high standards and was highly competitive.”

As Kyslytsya later learned, it was Maria Carlson—now professor emerita of Slavic languages & literatures and director emerita of what had been known as the KU Center for Russian & East European Studies, now CREES—who warned her Russian counterparts that if Ukrainian students were not included, no Russian students would be welcomed at KU either. So it was that Sergei Olegovich Kislitsa—the Russianized spelling of his Ukrainian name, which he used at the time—arrived at Kansas in fall 1992, with 20 or so Russians and four other Ukrainians.

“I understood that in Kansas, there was a very strong department of Central and Eastern European studies,” he says, “and it was a perfect match of my expectations. I knew that East Coast would always be available, especially in my profession, and the West Coast as well, so I needed to go see the heartland of the United States.”

One of his first discoveries, Kyslytsya recalls, was that enrollment here is a world apart from what he had known in the European and Ukrainian models: “In Europe, you come at the beginning of the year and everything is assigned to you, while here, so much responsibility is on you. That was quite a challenge.” He lived in Ellsworth Hall—“I had a crazy roommate,” he says with a laugh—and traveled when he could, including a Thanksgiving in Dodge City, Greyhound bus trips during winter and spring breaks to visit a friend in North Carolina, and holiday outings to Nebraska, where he stayed with American families. Kyslytsya delights in sharing a story about returning early from one such long weekend, only to find that his fellow Ellsworthians had chosen his closet to hide a contraband keg of beer for a party to which he had not been invited. “So I click, lock the door and go to bed, and they’re knock-knock-knocking, wanting their beer.”

As befitting a future diplomat, Kyslytsya closely watched human behavior, learning about American ways of life while also clarifying his existing insights into differences between Ukrainians and Russians. After their first two weeks on campus, the five Ukrainian students made no effort to interact and rarely saw one another; the Russians were rarely apart.

“I found, in many ways, how similar Ukrainians are to Americans, especially in Kansas, because Ukrainians are farmers, and Ukrainians—before the Bolsheviks took Ukraine—lived on individual farms, and we had individual ways of farming,” he says. “And so those Ukrainian students who came to Kansas with limited English proficiency, because they chose to be with Americans rather than stay together, by Christmas they were quite fluent, and by Easter they were even more fluent. This illustrates the particular feature about Ukrainians, and that is individuality. We are quite selfish people, but we can unite when there is national danger, the need to protect your country.

“It was quite a pity for me to see that the Russian students were spending time together all the time. When you go to a cafeteria, they would stay together. Or if you go to a cinema theatre, they would be there together. Who am I to judge? But when you come here, you want to integrate, you want to learn, you want to have to be on your own, because it makes you learn the culture, learn the habits, learn traditions, learn languages.”

Perhaps unlike most exchange students, Kyslytsya was “already quite advanced in my degree,” with a major in international law. He says now that, all things being equal, he might have preferred to complete his final semester and earn his degree here; instead, he had to finish at home while interviewing to join a foreign service bureaucracy that his homeland was quickly expanding. As Kyslytsya saw it, every extra day spent in Kansas could be an opportunity lost back home.

“When Ukraine became independent, the entire foreign service was only 100 people, and that included everyone from the minister to the driver. Today we have about 1,600 abroad and more than 600 in the capital. I joined the foreign service in 1993, and, ever since, this is where I have worked.”

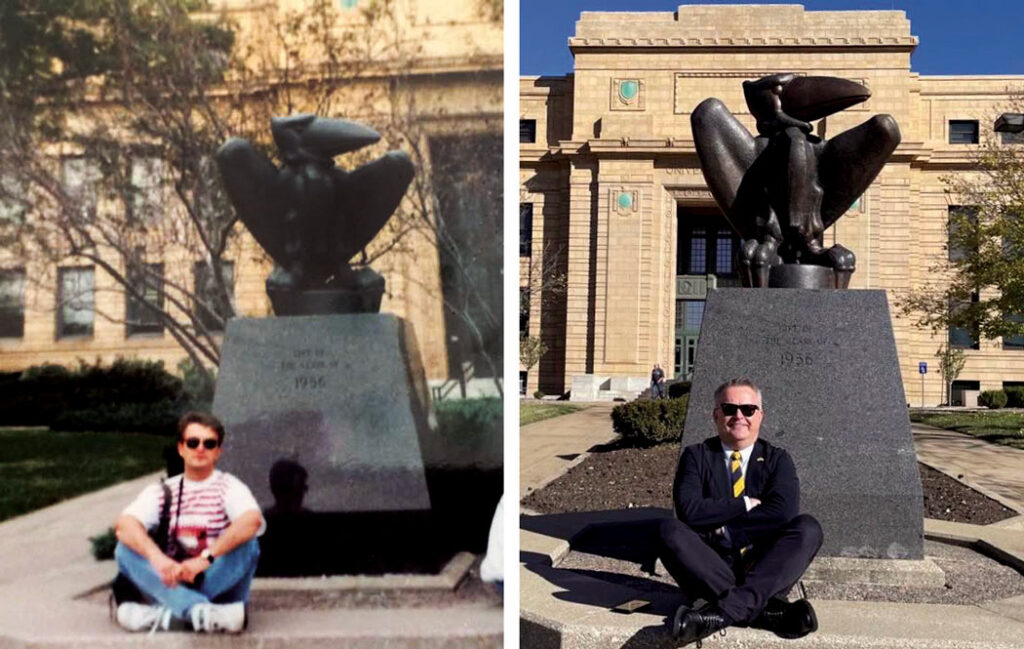

At the end of his visit last November, Kyslytsya arrived for a farewell dinner sporting a retro ’90s-style KU sweatshirt, a staple of student life that he could not afford as an exchange student. He had made time during his three days in Lawrence to search Mass Street shops for his souvenir. After returning to New York, Kyslytsya posted to Facebook before-and-after photographs that re-created his time as a KU student, posing in front of the Strong Hall Jayhawk and outside Spooner Hall—illustrating, most notably, that, from an era long before digital photographs all the way until today, Kyslytsya had saved his KU snapshots through the countless global transitions of a diplomat’s career.

“I am not a particularly sentimental person, but the warmth of the reception and of my conversations at The University of Kansas was amazing,” he wrote online. “Being back in Lawrence, KS, after more than three decades since I left, it revives some of the best and comfortable memories.”

So how is that KU, the Alumni Association and Kansas Alumni magazine had no clue that Ukraine’s ambassador and permanent representative to the United Nations was a Jayhawk? He was hardly an unknown, after all.

Named Ukraine’s U.N. ambassador in 2020, Kyslytsya had first become prominent in the international diplomatic jet set in 1998, when he was named chief of staff to Ukraine’s minister for foreign affairs, from there rising to such posts as political counselor to Ukraine’s U.S. embassy in Washington, D.C., and, in 2014, concurrent with Russia’s invasion of Crimea, deputy foreign minister.

Although he’d become famous, his name known around the world, his connection to KU was obscured by, well, his name: The Association’s alumni database had still listed him as Sergei Kislitsa—the Russianized name Sergiy was eager to shed after pledging himself to a career of international diplomacy on behalf of Ukraine—and the gap was never hurdled until a chance encounter in New York made possible by KU’s advanced—and rare—high-level instruction in Ukrainian language.

Among her other teaching and research duties, Associate Professor Oleksandra Wallo, director of graduate studies for the department of Slavic, German and Eurasian Studies and director of the KU Summer Language Institute in Lviv, Ukraine, teaches advanced Ukrainian. Because the course is available in a virtual format, it is popular for those in the military, government and international nonprofit organizations.

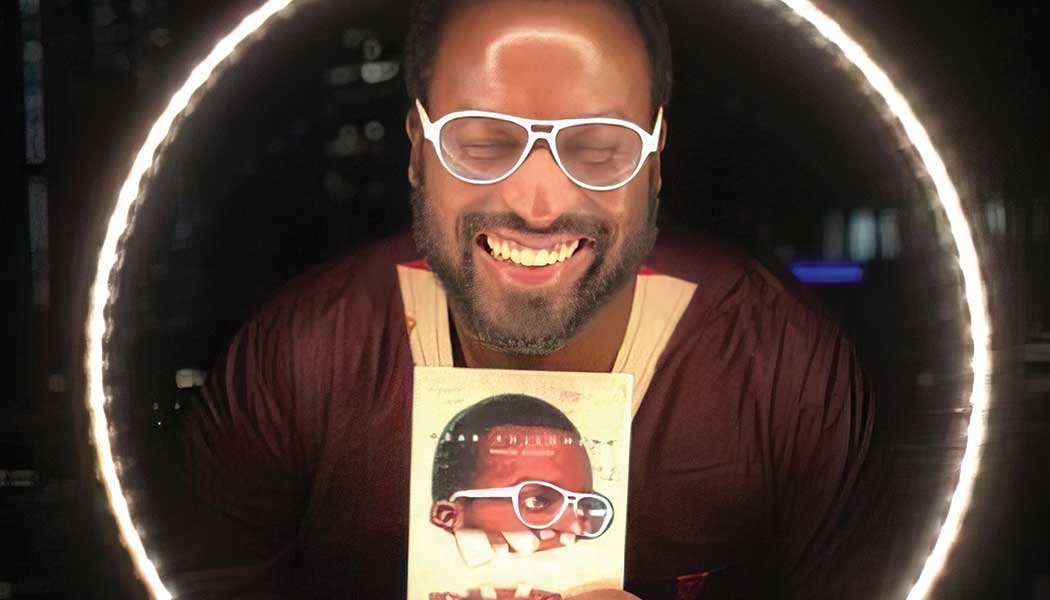

One of Wallo’s students, who happened to be cradling his textbook at the time, attended a New York City event that featured Kyslytsya; the ambassador took notice and asked him where he was studying Ukrainian. When the student replied, “KU,” Kyslytsya replied, “Actually, I went to KU and have very fond memories of it.” The student reported back to Wallo, who of course shared the exciting news with colleagues. Once the name-change riddle had been solved and records confirmed Kyslytsya’s KU experience, invitations were extended and arrangements finally made for him to give a public speech Nov. 12 at the Dole Institute of Politics.

His eagerness to return to Lawrence was evident in his travel schedule: Although his Dole Institute event was on a Tuesday evening, Kyslytsya arrived on that Sunday, Nov. 10, and on Nov. 11, Veterans Day, he joined Yaroslava Sochka, first secretary of Ukraine’s U.N. mission, for a wreath-laying ceremony at the Memorial Campanile before venturing out on his first special request: a visit to the Jayhawk Welcome Center at the Adams Alumni Center.

Kyslytsya seemed genuinely amazed at the glorious new home for welcoming visitors, alumni and prospective students and their families—and particularly delighted to see his name on the massive message screen usually reserved for greeting visiting high schoolers. He described the building’s creators as “heroes” and comfortably relaxed in the Adams Alumni Center’s pub with his traveling party and hosts. He later visited classes, met with faculty at downtown events, and, as the trip’s finale, delivered his insistent message on behalf of Ukraine at the Dole Institute.

“I hope it is very clear to the Americans that if America wants to be great, America cannot let Putin win the war against the civilized world,” he said in a press event with local reporters. “It’s a very banal statement—I had a conversation with Chris yesterday about banality—and I think it’s very simple. All the rest is conspiracy theories.”

To describe the ambassador’s speech as standing-room-only would imply standing room was available; in fact, the crowd reached into the hallway and even the exterior sidewalk, with latecomers listening through a series of open doors.

“It affirms the importance of KU as an internationally focused university based in Kansas,” Erik Scott says the ambassador’s visit. “It was both the international connections of KU and its strengths in Ukrainian and Eastern European studies that helped bring the ambassador here, but it’s also KU’s nature as a Midwestern research university that really made such an impression on the ambassador and made him want to come back. KU was a crucial step in his career.”

During his leisurely conversation in the pub, Kyslytsya recalled his favorite KU classes and teachers, in particular Professor Philip Schrodt’s International Conflict course. Reached at his home on the East Coast, where he is retired from a late-career stint as a consultant to U.S. intelligence agencies, Schrodt was thrilled to hear that his KU teaching and research are still paying dividends at the highest levels of global diplomacy. “I’m very proud of that class,” he says. “I think students got a sophisticated view of what war really is.”

Equally as important, Kyslytsya recalls, was a course on interpersonal communication in multicultural organizations. “Of course I use that every day,” the U.N. ambassador says, smiling. And, too, there was his English teacher, name since forgotten, who told the future diplomat: Young man, please get to the point.

“‘Say things in a very simple way. Do not hide between the lines what you want to say.’ And that was one of the best pieces of advice I was given. My sentences were too long. When I worked in Washington, D.C., there were instances when I would come back from the NSC or State Department, prepare a cable to report my meeting to the capital, and my boss, the ambassador, would tell me, ‘Why is your cable so banal?’ And I said, ‘Because my American counterpart was very banal. Very simple in his or her messages.’

“And that is the position. Don’t read between the lines, you know?”

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Top photo illustration by Chris Millspaugh

Photos by Dan Storey

Strong Hall photos courtesy of Sergiy Kyslytsya

/