Resilient and sustainable: KU’s 2024 campus master plan

Issue 1, 2024

Memories live within our private viewfinders, selfies and video clips that create personal social media feeds on endless loops. They are how all Jayhawks process, over lifetimes, formative years on the Hill, but any current visit to Mount Oread—a stroll down Jayhawk Boulevard, a picnic in Marvin Grove, a football afternoon, basketball evening or gallery getaway—provides abundant evidence that time moves on.

Things change. And not always for the better.

Enter the concept of a campus master plan, which provides a playbook for KU’s talented architects, planners, designers and engineers to ensure change is not merely good, but healthy.

The latest iteration in the century-plus cycle of KU master plans is currently being finalized for approval by the chancellor and provost for forwarding to the Kansas Board of Regents, which requires such updates every 10 years. This time around, though, even the concept, creation and intention of the plan have changed.

If, in earlier times of KU’s dynamic growth—in both place and purpose—master plans resembled shopping lists, the current version is perhaps more akin to a budget.

“We knew we had some needs,” says University Architect Mark Reiske, “but we also believed that we didn’t really have to build a lot.”

Turns out, our hilltop household already has much of what it requires to exist comfortably and securely. Now, how can we sharpen the Jayhawk family’s resource management? How can we do more, much more, with less? How do we lovingly turn our attention from wants to needs, a concept that Reiske, a’86, refers to as “rightsizing” campus.

“This,” Reiske insists, “is so much not a typical master plan.”

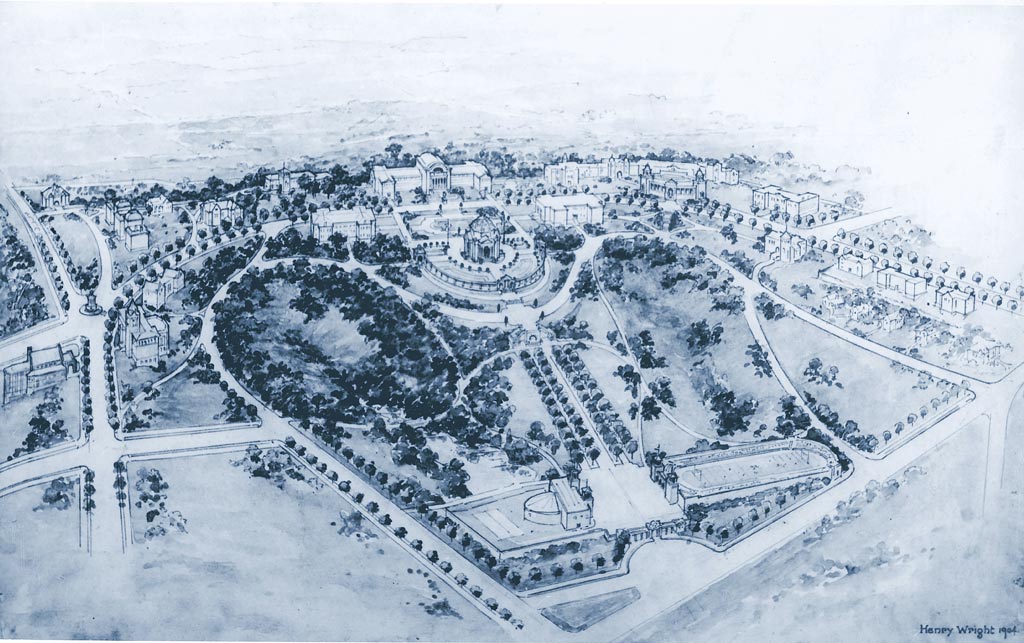

KU’s first master plan was drafted in 1904 by a pair of noted landscape architects, both of whom favored open green spaces: George Kessler, the visionary behind Kansas City’s interwoven parks and boulevards, and Lawrence-born Henry Wright, who was only 23 when he partnered with Kessler in designing the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis.

The primary influence of their Mount Oread vision was to shift campus to the south and west, along the ridge, and direct future expansion down the Hill. The Kansas City firm Hare & Hare in 1928 and 1932 drafted plans that introduced Strong Hall as the campus centerpiece and anchored the University along the spine of campus, Jayhawk Boulevard.

Internal planning by Alton Thomas, landscape architect from 1948 to 1983, and Vice Chancellor R. Keith Lawton, b’47, director of facilities planning, brought to post-World War II campus such innovations as intentional designs for trees and other plantings and development of Memorial Drive. The Board of Regents in 1973 began requiring formal planning documents, which continued the University’s evolution into a comprehensive research and educational complex, and KU planners in 1997 followed up with a 20-year plan that addressed such topics as future building sites, traffic flow and transportation needs, and preservation of campus beauty.

In an era of limited state support for new construction, 2014’s 10-year master plan, supporting the Bold Aspirations strategic plan, led to $737 million being spent on 40 major projects. That included such landmark developments as the $350 million Central District, anchored by Gray-Little Hall and the Burge Union; the DeBruce and Earth, Energy & Environment centers; and Capitol Federal Hall. When his 41-year KU career closed in 2021, University Architect Jim Modig, a’73, had guided or had been significantly involved in 168 construction and renovation projects worth $1.5 billion.

The current master plan, created to support the Jayhawks Rising strategic plan, envisions only three new Lawrence building projects—a much-needed health and wellness center; a new interdisciplinary science building, dubbed ISB2; and reconstruction of David Booth Kansas Memorial Stadium and development of the historic site’s planned conference center and Gateway District—along with “resets” for Lindley and Twente halls and Robinson Center, and renovations and additions for Anschutz Library’s student success center, the schools of architecture and law, and Watson Library.

Outside of those projects, the plan, as proposed by consultants Perkins & Will and Multistudio, is more about looking inward, a self-reflection on who we are and how we can best succeed, both now and long into the future.

“Perkins & Will is as thrilled about this as we are. It excites them beyond belief, because they’ve never done a master plan like this,” Reiske says. “Usually the state of Kansas follows the coasts by about 10 years. This is one time where we’re actually very forward-thinking, regarding how we become resilient and sustainable, looking to the future. Everyone is going to have to do something similar. I think this gives KU the best chance of, 100 years from now, being the place everyone’s proud of today.”

Gautam Sundaram, Perkins & Will’s Boston studio principal and a leader in its urban design practice, has worked in higher education planning for more than 20 years. He first arrived on Mount Oread nearly two years ago, while campus, as everywhere, was still grappling with COVID-19 restrictions.

He says he found here a beautiful campus where leaders—including Chancellor Doug Girod and Provost Barbara Bichelmeyer, j’82, c’86, g’88, PhD’92, along with their design and operations teams—had embraced the need to find the best road forward into eras of stable or declining on-campus populations, which have the potential to become an existential crisis for higher education across the country. It seems the opportunity Sundaram had been searching for presented itself when he first read Reiske’s request for proposals, and his connection with KU has since grown so strong that he now uses “we” when discussing all things KU.

“This is really unlike any other campus master plan,” Sundaram told Kansas Alumni in an interview from his Boston office. In an era of post-COVID changes to learning environments and workplace trends, Sundaram saw at KU the chance to implement a data-driven approach that, given enough input, can create a toolkit, along with a real-time dashboard offering updated data across a massive range of variables, for University leadership to continually assess needs and resources.

Earlier master plans boasted of hundreds of interviews with students, faculty and staff; Sundaram and his team gathered information from thousands of interactions—“5,000 touch points,” in his description—that allowed for creation of a fluid document that is more like a flow-chart algorithm than an architectural blueprint.

“We’ve kind of framed the story around finding the beauty in rightsizing,” he says. “It doesn’t have to have a negative connotation, or negative idea. It’s something that actually allows you to do far more powerful, and experiential, aspects.”

Eighteen months of research revealed patterns that startled Sundaram, notably the deep affection Jayhawks have for the campus landscape, especially the site that he identified as the heart of campus: Wescoe Hall, Wescoe Beach and surrounding open spaces, all of which are loved and loathed in equal measure.

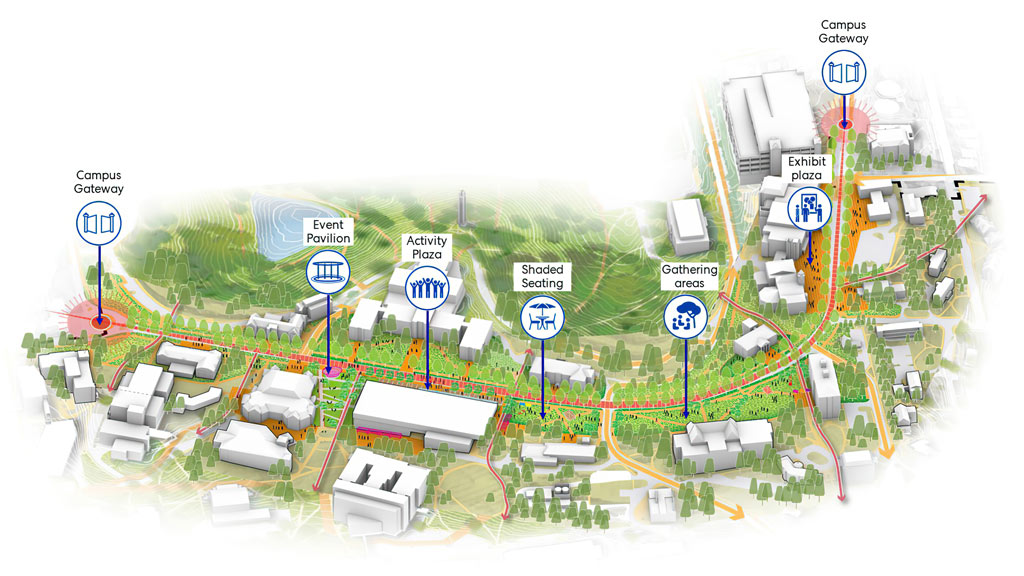

Options for improving Wescoe reflect much of the design focus proposed for all of campus: refining public plazas and green spaces, fashioning terraced nodes along the south slope, even replacing the old concrete beach with an amphitheater-style pavilion that attracts group interactions all day long and into the evenings—all of which is more about embracing a change in vision than funding massive capital improvement projects.

In other words, mind over money.

“This whole data-driven and toolkit approach is critical, because it assembles the data in a manner that allows everybody to understand where the gaps are,” Sundaram says, “and empowers the KU community to start making the decisions required of them to put us in a much better place.”

Among the plan’s numerous areas of interest, Sundaram highlights an emphasis on sustainable natural and built environments, biodiverse green spaces that include greenway hiking trails and bike paths, mitigating heat islands worsened by ongoing climate change, increased shading and thinned undergrowth along walkways, and designs for outdoor spaces that remind the KU community that our “quad”—a desire he says was referenced repeatedly in his interviews—is already plentiful and beautiful, but goes by a different name: Jayhawk Boulevard.

What some might see merely as lawns or hillsides, Sundaram views as potential learning environments where campus denizens and visitors alike are naturally invited to pause, rest, study, chat.

“These different moments will start to create opportunities for gathering and respite,” Sundaram says, “completely transforming Jayhawk Boulevard into a series of programmable spaces that become active for all community members.”

The 18 months of research behind the current master plan proposal confirmed a dire situation campus leaders were already aware of: The University has more than 900,000 square feet of extra space in its rapidly transforming learning environments, and that extra space weighs heavily on a campus already burdened by an estimated $750 million in deferred maintenance.

It is an overwhelming number that, for decades, has seemed impossible to surmount. Until now.

Reiske explains that a KU software suite called Maximo currently tracks such vital data as work orders, enrollments, and usage of every seat in every classroom on campus. With that information, KU operations leaders can direct limited maintenance funds to the most highly used classrooms that need the most work.

Along with the master plan’s new toolkit, KU planners now have access to real-time data on enrollment, office assignments and building conditions ranked in four specific categories, all of which will help direct looming tough decisions on how best to pull some campus space offline and out of the deferred maintenance logs, with the intention of not spending good money on bad options.

“We want to make sure that this institution is resilient and sustainable for generations to come,” Bichelmeyer said at one of two town hall meetings where Sundaram introduced the proposed master plan to campus audiences. “This isn’t just about the next 10 years. This is about planning for the next 100 or so, and thinking about how we do our job as stewards at this moment in time to help drive toward that kind of future.”

As deeply as Mark Reiske cares for the nostalgia of Mount Oread—a sentiment he personally embraces as an alumnus who bleeds crimson and blue—he also acknowledges his professional responsibility to rip significant chunks out of the deferred maintenance backlog for the University’s present and future financial stability. He’s already bracing for blowback that he knows will come.

“One of the great things about KU—and I do sincerely mean this—is how passionately people love everything that is KU,” Reiske says. “It will be very difficult to step away from buildings. We will have any number of people who truly believe that we should never step away from any buildings, ever, so no matter what we decide to sell, or liquidate, or close, or mothball, someone will have very strong feelings about that from their time at KU.

“As I said, we should be so proud that people care so deeply about campus. At the same time, we’ve got to make hard decisions so that we can maintain buildings for generations to come.”

In discussing the tough decisions that await KU planners—all of which will be guided by the new master plan and its high-tech, data-driven toolkit—Reiske draws comparisons with gardeners culling their crops, resulting both in fewer plants to tend and more and better tomatoes. He also carefully notes that “historic doesn’t equal old” and “there’s a lot more to historic than just an age.” KU’s “signature” buildings, regardless of age, are deserving of more resources than others, he explains, and alumni need to support the critical need for rightsizing the campus environment.

“Business as usual is not sustainable for us any longer,” Reiske says. “It’s probably very hard for our alumni to understand this, because we’re saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got the biggest freshman class in the history of the University, and next year we’ll probably have a bigger freshman class,’ so they’re seeing all these students coming in. But what they don’t see is a cliff. The chancellor and provost are desperately trying to make us resilient to that cliff,” which refers to a plummet in the population of 18-year-olds in 2026, 18 years after the Great Recession.

A grim tone that inevitably accompanies talk of tough times does not represent the spirit surrounding the new master plan. Campus leaders are thrilled for the opportunities it presents, delivering up-to-date information that will help them create premium research environments, attractive high-traffic areas for student and faculty interaction, and properly maintained havens for outdoor living and private contemplations.

“This will allow us to be better than we are, and we have to be,” Reiske says. “In the market we’re working in, we have to be better.”

Better, in fact, than ever. Not in spite of the change we know is going to come, but because of it.

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Top photo by Andy White/KU Marketing

Photos by Steve Puppe

1904 master plan courtesy of University Archives

Campus renderings courtesy of Perkins & Will

/